Exactly one century ago this year, the United States extended the right to vote to women. To commemorate the centennial of this event, which has helped to shape American politics and society ever since, the WLA has been featuring events, exhibits, activities, and many other ways to learn about the fight for suffrage. One little-known chapter of American suffragist tactics that we’re highlighting is the suffrage cookbook.

It might sound comical. How could a suffragist make a cookbook? Didn’t these women want to step out of the kitchen and into the public realm? Through research and experimental baking, I set out to see what I could learn about the fight for suffrage.

Food is always political. It carries ideas about what is good, healthy, or comforting, as well as distasteful or immoral. It shapes our relationships and links the people who produce, make, and consume it. To bring cooking into the suffrage fight, suffragists made it political in a new way.

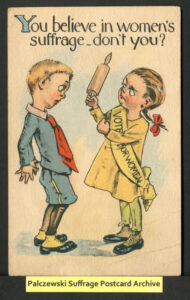

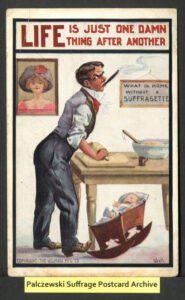

Suffragists had to confront claims that participation in politics would destroy women’s femininity and emasculate men. What better proof of their femininity and domestic expertise than a book full of recipes and household tips? What better way to show that suffragists intended to keep their domestic roles, and not threaten men in the public sphere?

Published by national and state-level suffrage groups, the books were sold as fundraisers. Some, like The Woman’s Suffrage Cookbook (1890) and The Washington Women’s Cookbook (1909) (with the banner “Votes for Women, Good Things to Eat”), give the name of each recipe’s author. The Suffrage Cook Book (1915), which I chose for my baking experiment, leaves the recipes mostly unattributed but generously sprinkles in quotes from men in politics supporting women’s suffrage and adages about women’s political voice. Reports on the progress of suffrage and detailed arguments for the cause appear in every book, tucked between recipes or in their own chapter at the end.

The recipes themselves are surprisingly similar across these books. It is easy to imagine that they represent the ‘average’ American kitchen. They seem to agree on tools and make assumptions about their readers’ knowledge; for example, the Jam Cake recipe I adapted below had but one single instruction: “Bake in a slow oven.”

Despite this homogeneity, many different women wanted the vote for vastly different reasons. These cookbooks were written primarily by white, middle-class suffragists, reflecting their ideas about food, the home, and politics while leaving out other points of view held by other groups of suffragists. The recipes are overwhelmingly Anglo-American, along with a handful of German and Swedish recipes—from immigrant groups seen as more acceptable. Meanwhile, other significant minority groups are absent, such as African American, Latinx, Irish, Jewish, Chinese, and Native American. This absence says something about who was accepted into the suffragist elite, and whose food fit with the authors’ ideal of American femininity on show.

Searching for rationales that would convince men to grant them suffrage, some white women pointed to their own education and social status. Why, they argued, should they be denied the vote when less educated men (namely Italian immigrants and African Americans) had that right? The awful extreme of the argument, which appears occasionally in the cookbooks, saw it as a trade: the vote should be taken away from “undesirable” men and given to white women, who “deserved” it.

Some suffrage leaders who did not agree with these ideas struggled with the morality of allowing such ideas into their movement, yet they needed a wide base of support to get enough states to ratify their amendment. Perhaps it is easy to imagine how African American suffragists felt upon hearing such an argument from white women who claimed to share their goals. Ultimately, the 1920 victory only allowed white women to vote. African American women’s victory came 45 years later, with the Voting Rights Act. Suffrage still remains beyond the reach of many in America.

So what can we learn from these cookbooks?

The history of the suffrage movement, seen in these cookbook pages, shows us the difficulties of building strong coalitions across an enormous, diverse country in the name of national change. The cookbooks also reveal the very physical nature of an ideological fight: any push for change needs support of human effort and monetary funding.

Today, food can still be a powerful tool to meet these needs. This past June, a group of professional chefs called Bakers Against Racism organized a bake sale to raise money for human rights and justice causes. Through social media, professional and amateur bakers around the world joined in, turning it into an international bake sale raising nearly 1.9 million dollars. With offshoot bake sales continuing and a current Bake the Vote bake sale raising money for a fair election, Bakers Against Racism represents a fascinating modern counterpoint to these century-old cookbooks. Vastly more diverse, and started by people of color, the current movement embraces today’s technology by reaching people via social media and encouraging all eager bakers to help support the campaign for justice through food.

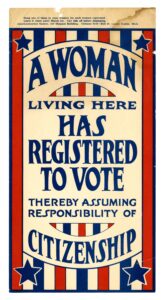

The road to the ballot box is just as complex as the rest of American history. Suffrage—the right to vote—affects every aspect of our lives. Suffragists recognized that our choices at the ballot box determine how our towns, cities, states, and country work, what they prioritize, and how we interact with them, as well as how we work and pursue our passions, regardless of gender. Suffrage determines whose voices can be heard. They also knew that the choices on the ballot have never been ideal. But if no one saw a reason to fight for a step forward, we may never have seen suffrage for any women at all. We may never have seen women pursue careers in politics or activist leadership, like those whose papers we hold at the WLA, such as Carol Moseley Braun and Mollie Lieber West.

The right to vote is a hard-fought right, and its expansion has taken decades more of concerted efforts in an imperfect world, despite generations of people seeking to hold others back from the ballot box. One hundred years later, we have the benefit of time to learn lessons from the past, and to understand the power of the vote.

But it only works if we use it.

Make your plan to vote today.

To find your voting information: VOTE411.org from the League of Women Voters

To learn more about diversity in the suffrage movement, check out this Smithsonian Magazine article.

Jam Cake (adapted from The Suffrage Cook Book (1915))

Adapting the recipe:

After investigating unfamiliar ingredients, such as sour milk, I dug into my cookbook collection, studying the order of ingredients and actions to find a cake recipe that matched the quantities of flour, sugar, fat, and leavening listed. Finally, after studying “creamed” recipes (which start by creaming the butter with the sugar until fluffy), I realized that the order of ingredients listed almost perfectly matched the order used in a creamed cake batter. My new theory was that when no steps are given, readers knew to combine ingredients in the order they appeared. The results? A dense, moist cake flavored with spices and jam, with a sunken, slightly gooey center (alright, so it needs a little more testing, though I prefer it this way!).

- 1 cup brown sugar, packed

- 2/3 cup butter, softened and at room temperature

- 3 eggs

- About ¾ cup of strawberry jam or preserves

- 1 tsp ground cloves

- 1 tsp ground cinnamon

- ½ tsp grated nutmeg

- Just under ½ cup whole milk

- 1 ½ tsp lemon juice

- 1 tsp baking soda

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

Preheat your oven to 325 F. Butter an 8-inch round cake pan and lightly flour it. Tap out the excess.

Squeeze the lemon juice into a glass measuring cup and pour milk in up to the ½ cup mark. Let sit for 5 minutes to become “sour milk.”

Measure out your flour and baking soda in a medium bowl and whisk together. Set aside.

In a large bowl, cream the butter and brown sugar until fluffy, using a stand mixer or handheld mixer (or a whisk, though this will take longer.) Keep mixing, adding the eggs one at a time until incorporated.

Add in the jam and keep mixing until combined.

Sprinkle in the spices (cloves, cinnamon, and nutmeg) and pour in the sour milk. Mix at a low speed until combined.

Add in the flour mixture and switch to stirring gently with a wooden spoon. When there are no more dry flour bits and the batter looks well-combined, pour into your prepared cake pan and bake until the center no longer jiggles and a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean.

Let cool for 10 minutes, then run a knife around the edge gently and flip the cake out, then flip it right-side-up on a rack to cool. The center will likely cave in.

And serve! While enjoying this taste of history, reflect on the ways women’s suffrage has changed our world and our lives, and how we can best honor its history today.

Scarlett is a Sesquicentennial Scholar at the WLA and is in the second year of the Public History MA Program. A Chicago-area local, she enjoys baking, singing, and chasing birds with a camera.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.