During the spring of 2020, I had plans to create an online exhibit exploring the unprocessed Eleanor Foundation collection at the Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). I began research before the pandemic, but interrupted access to physical collections halted the exhibition’s production. Reduced physical staffing for de-densification of campus and prioritization of teaching and research inquires halted the progress of making the publication of the exhibit, but the information gathered from the attempted display deserves light. This blog discusses some aspects of the Eleanor Foundation, working with an unprocessed collection, and future research potential. When I took the photos that appear in this blog, I did not intend to publish them, only to aid me in my research. Due to this, the quality of the images is lower than in other WLA blogs.

Eleanor Foundation Synopsis:

Conversations with working women inspired Ina Law Robertson (Figure 1), a University of Chicago graduate student, to create safe living spaces for them. In 1898, she opened a three-story building called the Hotel Eleanor, starting her dream of creating affordable housing. From there, the Eleanor Association (name later changed to the Eleanor Foundation) opened a total of six housing units called clubs, a camp (Figure 2), and other social gathering spots. Robertson died in 1916, but the Foundation lives on, now as part of the Chicago Foundation for Women.

Navigating an Unprocessed Collection and Interesting Items:

Working with an unprocessed collection means there is no finding aid. An archival worker took an inventory of the boxes during the accessioning process, but it was very vague. One of my firsts tasks was reading through the inventory and marking anything that might help me better understand the Eleanor Foundation and its beginnings. The inventory gave me a couple of ideas of where to start, but I had no clue what I would find.

Some documents provided more questions than answers. For example, I came across a 1980s biography of Ina Law Robertson and a brief history of the Central Eleanor Club. The biography had lots of detailed stories, but I could not sort out any myths since there were no sources. She intrigued me because she refused to affiliate with a religious institution, provided funding from being an estate holder, and the fact that she did all of this seemingly by herself. I wanted to know more from her viewpoint. The Central Eleanor Club history provided me with more mystery. The way the first page reads implies that the Central Eleanor Club was partially separate from the Eleanor Foundation (Figure 4). I wanted to know more about the hierarchy of the Foundation and its branches like the Central Eleanor Club.

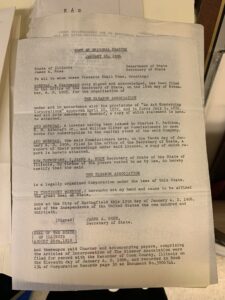

The only document I found that dated close to the beginning of the Eleanor Foundation’s origin was the original charter (Figure 5). The 1906 charter provided a sense of authority to the organization since Illinois recognized it, but it alone did not tell me any more than that.

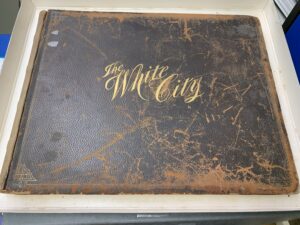

Early March 2020, Loyola University Chicago took pandemic precautions and limited the number of students on campus. I knew I needed to take more photos of items for research, but I thought I would be able to go back to the archives before the end of the semester. While I did not find more materials related to the Foundation’s origins on my last day with the collection, I did find some exciting items such as The White City book with photographs from the 1894 World’s Fair (Figure 6), songbooks used at Camp Eleanor (Figure 7), camp memorabilia, memorial bricks, printing press blocks (Figure 8), and Ina Law Robertson’s Bible with bible study notes (Figure 9).

Open-ended Conclusion:

Without access to the physical collection, I struggled to answer my questions about Ina Law Robertson and the Eleanor Foundation. As I compiled the information I had for the exhibit, I started a running list of inquiries. Whenever additional workers are allowed back on campus, the exhibition will be published with higher quality photos and scans. Maybe I will have the chance to find answers to questions about what the Foundation did during the suffrage movement and the connection between Jane Addams and the Hull-House with Ina Law Robertson and the Eleanor Clubs.

The Eleanor Foundation Collection has vast research potential. Historians studying Chicago, housing, and women’s history are just some of the scholars who would find this collection intriguing. Some of my lingering questions include: What was the Eleanor Foundation’s connection with women’s suffrage? (Reading the Eleanor Records 1915-1920 may provide insight); What effects did World War II have on the clubs – more working women so what did that mean for the clubs? Did company housing create competition? Were women given better pay and could live elsewhere? Did membership numbers go down? What was Ina Law Robertson struggles as an unmarried woman? What were her struggles as a business woman? What are the connections to Jane Addams? Jane Addams spoke at a club opening, but is there a transcript of the speech? Were there letters between Ina and Jane? Archives have and will always have backlogs and unprocessed collections. This blog and the future exhibit are designed to raise curiosity. Secrets are waiting to come out of this collection.

Miranda is a graduate assistant at the Women and Leadership Archives. She is a second year Public History Master’s student. Her dream job is work in a museum, possibly with collections. She enjoys studying dance history as well as 20th century social changes. In her free time, she tap dances!