This post is part of a series on the WLA Blog by guest writers. These writers are graduate students in the Public History program at Loyola University Chicago. Each visited the archives during Fall 2021, delved into the collections, and wrote about a topic not yet explored here. We are excited to share their research and perspectives.

With professors involved in the civil rights, anti-war, and women’s rights movements, Mundelein College in the mid- and late-twentieth century could certainly boast a large group of progressive and vivacious faculty members. Yet to many people, Sister Mary DeCock, BVM stood out from this already-exceptional group. Other Mundelein colleagues named DeCock personally as one of the most radical and spontaneous faculty members at the College [1].According to colleague David Orr, DeCock was part of a select group of “crazy folks” on campus who were perpetually busy in their teaching and administrative duties, and in developing new programming such as Mundelein’s Weekend College [2]. A staunch feminist and global scholar, DeCock spent several decades at Mundelein College and Loyola University Chicago researching and teaching on women, feminism, and liberation theology.

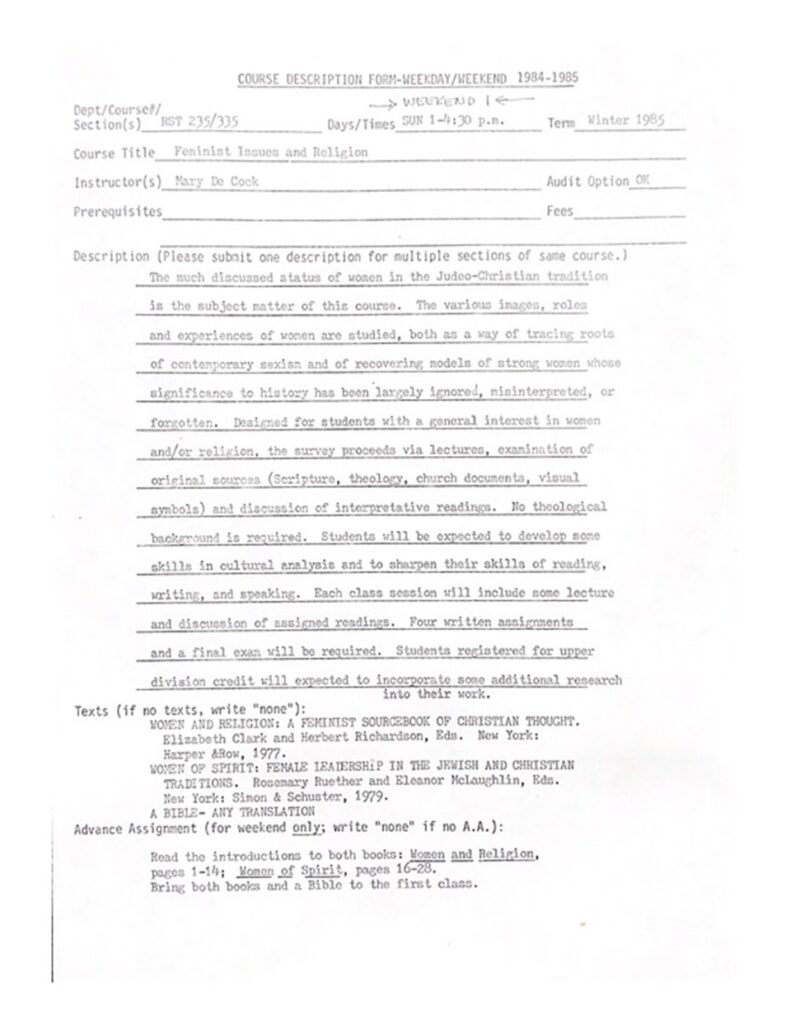

Born in 1923 in De Witt, Iowa, DeCock joined the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM) as a young woman before obtaining her graduate degree in English. She arrived at Mundelein in 1955. She eventually ended up teaching in Mundelein’s religion department, where she focused heavily on social justice, race, and feminism in her teaching [3].With classes such as “Feminist Issues and Religion” and “Women, Religion, and Social Change,” as DeCock became further committed to her students and the Mundelein community, she dropped out of her University of Chicago PhD program in Social Ethics to devote her time solely to teaching and social justice work [4]. DeCock served on committees surrounding feminist issues, set up lecture series on women’s history, and developed a particular interest in women’sissues in her scholarly research and writing [5]. She paid special attention to Marian theologyand the history of the BVM in her own work [6].

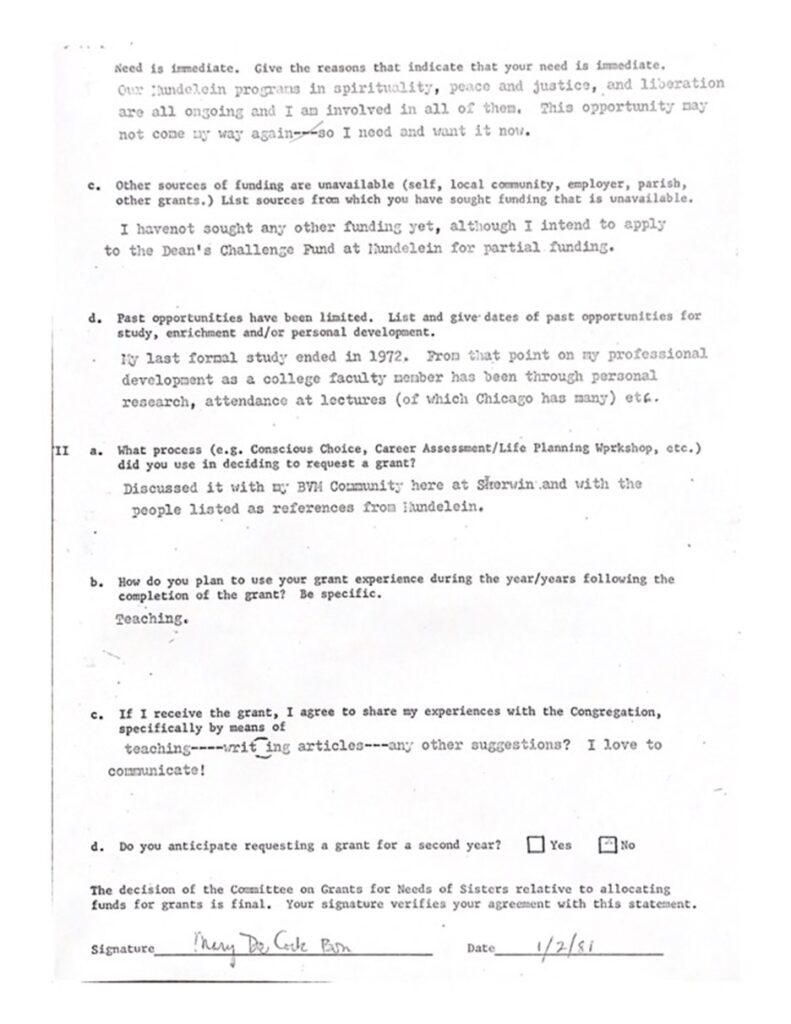

DeCock’s feminist work, however, was not confined to Chicago. In the summer of 1981,she joined a study trip that took participants to Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru [7]. This trip occurred through the Eighth Day Center for Justice, a group of Catholic congregations dedicated to fighting oppression and promoting equality [8]. DeCock later shared that her desire to under take this seven week-long journey grew out of changes in the Church. The Church had evolved in the 1960s to allow more freedom for sisters in their social justice work, and she wanted to take full advantage of this transformation [9].

For DeCock, the goals of the trip were two-fold. First, she sought to observe women and their treatment in these various countries [10]. This goal manifested itself particularly in the journal she kept while studying in Mexico City in June of 1981. Between complaints about the rain and jokes that the Mexican food she was eating might cause weight gain, DeCock was particularly concerned with the experiences of the local women that she encountered. She quickly declared in the journal that she would fill its pages with “questions, notes,” and observations regarding these women [11]. She worried about their plight as she described the poverty, alcoholism, and back-breaking labor that she observed, but still found something positive in their experiences: “Without the Church,” she posited, these women “would have a much drearier life” [12].

DeCock’s second goal for the study trip was to explore a new scholarly interest: liberation theology. Liberation theology is a Catholic movement that emphasizes social justice and the liberation of those who are exploited and oppressed [13]. DeCock had been curious about the concept before the trip; as she wrote in a funding application, she was excited to meet “leaders in South American liberation theology… which are solely reconstructing the race of the Church on that continent” [14]. She felt that it was one thing to read about the theory, but it was entirely different to experience it face-to-face [15]. When actually meeting with leaders and experiencing a movement in action, DeCock stated, “you come back with a whole different attitude” [16]. She eventually led her own study trip to Nicaragua in 1983, guiding graduate students in exploring South American liberation theology for themselves [17].

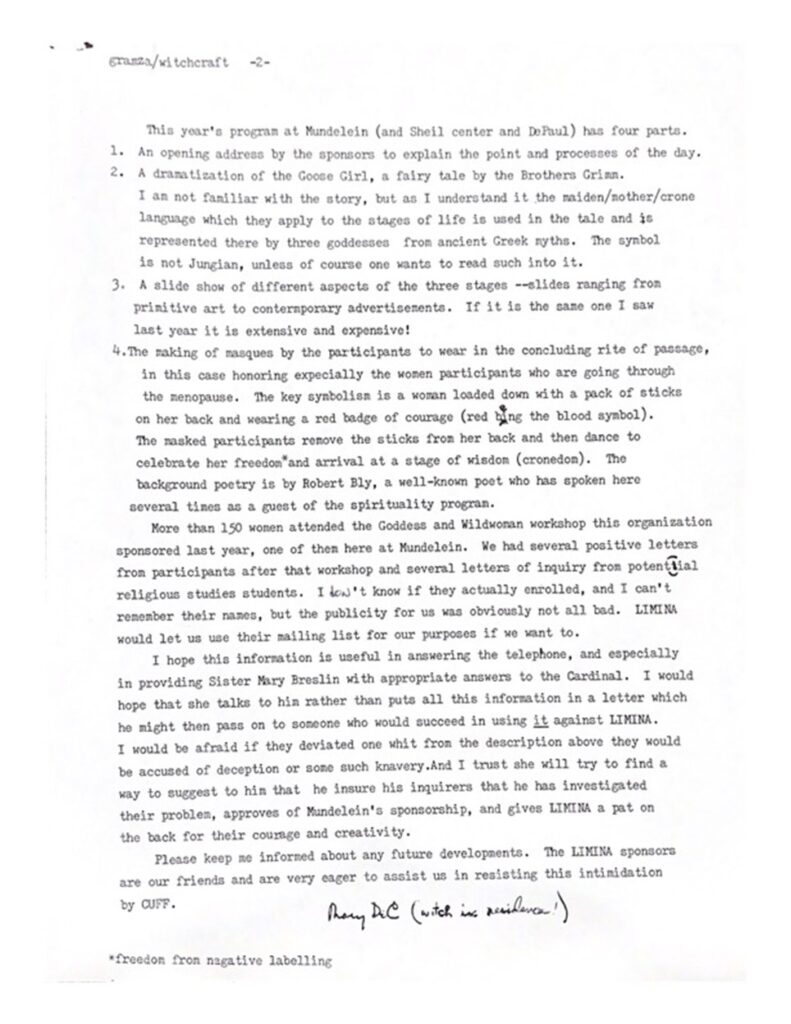

During the mid-1980s, DeCock pushed her progressive and feminist interests further even as she stayed physically closer to home. In 1986, a mild scandal hit Mundelein College. Limina, a local group that celebrated womanhood, rites of passage, and dance, was set to hold a program entitled “Her Holiness: Maiden, Mother, Crone” at Mundelein on March 15th [18]. Newspapers picked up on other Limina events in the Chicago area, and rumors began swirling that Limina’s practices were anti-Catholic and involved witchcraft [19]. Throughout the scandal, DeCock advocated for Limina, insisting that the group was Catholic-affiliated and simply provided women a way to build confidence and self-esteem [20]. She even had a bit of fun with the scandal, (seemingly) jokingly signing a letter regarding the situation as “Mary DeC (witch in residence!)” [21].

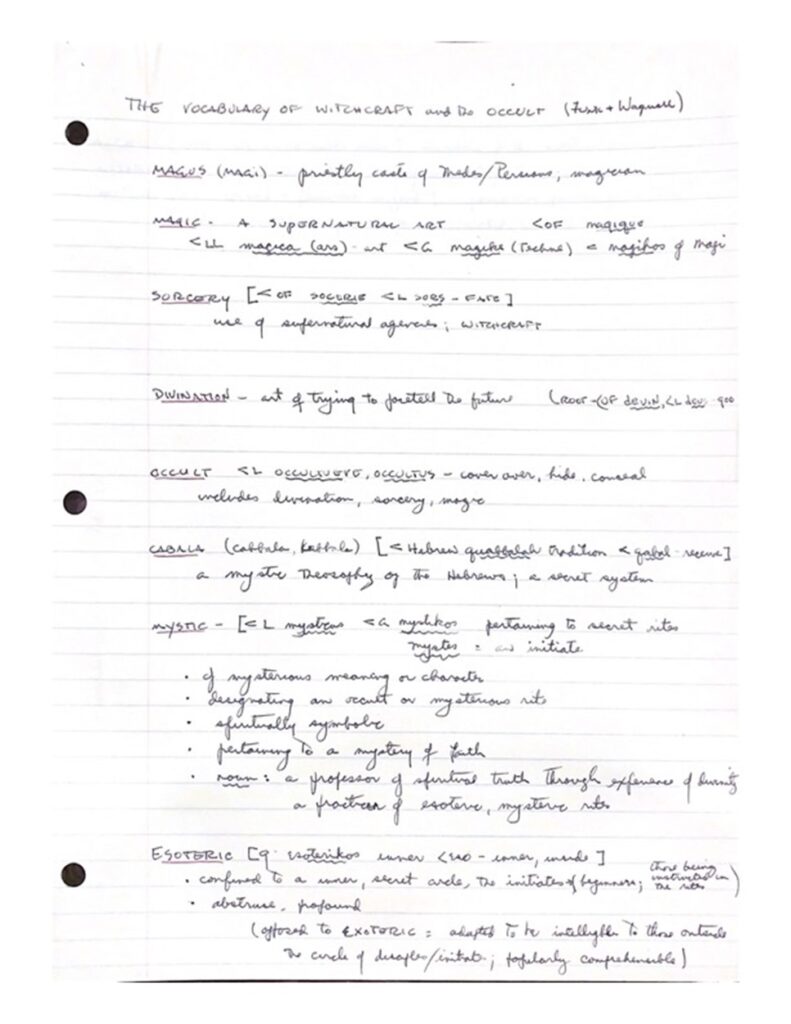

Once the controversy blew over, it appears that DeCock remained interested in witchcraft and magic. Papers and notes show that she devoted continued study to the subject [22]. With her interests in feminism, Marian theology, and folk religion, it is likely that DeCock found connections between the topic of witchcraft and her other research. Yet the confidence shown in studying, taking notes, and collecting readings on the controversial subject of witchcraft as a Catholic sister is a perfect illustration of DeCock’s progressive views and open-mindedness.

Sister Mary DeCock passed away in 2010, having taught at Mundelein College and Loyola University Chicago for fifty years. She left behind dozens of publications and other writings, as well as her collection of papers in the Women and Leadership Archives. Most of all, she left behind a legacy of dedication and commitment to social justice and interdisciplinary teaching and learning that lives on in the mission of Loyola University Chicago today.

Caroline is in her first year of Loyola’s Public History Master’s program. She graduated from Luther College in 2021 with her Bachelor’s in History and Museum Studies. Her research interests include trauma memorialization, women’s history, and Australian history.

Endnotes

[1] Orr, David. Interview by Elizabeth Fraterrigo. November 18, 1998. Tape Recording. Mundelein College History Project. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago; Crowley, Sister Joan Frances, BVM. Interview by Lisa Oppenheim. November 16,1998. Tape Recording. Mundelein College History Project. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

[2] Orr, David. Interview by Elizabeth Fraterrigo. November 18, 1998. Tape Recording. Mundelein College History Project. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

[3] DeCock, Mary, BVM. Interview by David Cholewiak. November 3, 1998. Tape Recording. Mundelein College History Project. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.[4] DeCock, Mary, BVM. Interview by David Cholewiak. November 3, 1998. Tape Recording. Mundelein College History Project. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago; Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 9. “Feminist Issues and Religion” course description, spring 1982; Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 4.Folder 6. “Women, Religion, and Social Change” course assignments, fall 1993.

[5] DeCock, Mary, BVM. Interview by David Cholewiak. November 3, 1998. Tape Recording. Mundelein College History Project. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

[6] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 2. Folder 10; Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 5. Folder 2.

[7] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 1. Folder 10. Sr. Mary DeCock, BVM to the Dean’s Challenge Fund Committee of Mundelein College, May 10, 1981.

[8] “Mission and Vision.” 8th Day Center for Justice. Accessed November 15, 2021.https://8thdaycenter.org/mission; Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 1. Folder 10. Application for funding through the Committee on Grants for Needs of Sisters, BVM Center.

[9] DeCock, Mary, BVM. Interview by David Cholewiak. November 3, 1998. Tape Recording. Mundelein College History Project. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

[10] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 1. Folder 10. Application for funding through the Committee on Grants for Needs of Sisters, BVM Center.

[11] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 1. DeCock Mexico City journal, June 1981, 5.

[12] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 1. DeCock Mexico City journal, June 1981, 6.

[13] Dault, Kira. “What is Liberation Theology?” U.S. Catholic. October 14, 2014.https://uscatholic.org/articles/201410/what-is-liberation-theology/.

[14] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 1. Folder 10. Application for funding through the Committee on Grants for Needs of Sisters, BVM Center.

[15] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 4. Folder 11. “Consciousness-Raising Experiences in Latin America.”

[16] DeCock, Mary, BVM. Interview by David Cholewiak. November 3, 1998. Tape Recording. Mundelein College History Project. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

[17] DeCock, Mary, BVM. Interview by David Cholewiak. November 3, 1998. Tape Recording. Mundelein College History Project. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

[18] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 4. Sister Mary DeCock, BVM, to Marianne Gramza, February 19, 1986;Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 4. “Witchcraft Charged by CRA,” Bob Kostanczuk, The Daily Calumet, March 10,1986.

[19] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 4. “Witchcraft Charged by CRA,” Bob Kostanczuk, The Daily Calumet, March 10, 1986; Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 4. “Fertility Dancing with the Goddesses,” Jason Karlawish; Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 4. Sister Elena Malits, CSC, to His Eminence Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, March 3,1986; Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 4. His Eminence Joseph Cardinal Bernardin to Sister Elena Malits, CSC, March 11, 1986.

[20] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 4. Sister Mary DeCock, BVM, to Marianne Gramza, February 19, 1986.[21] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 4. Sister Mary DeCock, BVM, to Marianne Gramza, February 19, 1986.

[22] Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mary DeCock, BVM, Papers. Box 3. Folder 4.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.Questions? Please contact the WLA at wlarchives@LUC.edu.