This post is part of the WLA blog’s 2022 series written by guest writers. These writers are graduate students in the Public History program at Loyola University Chicago. Each visited the archives during Fall 2021, delved into the collections, and wrote about a topic not yet explored here. We are excited to share their research and perspectives!

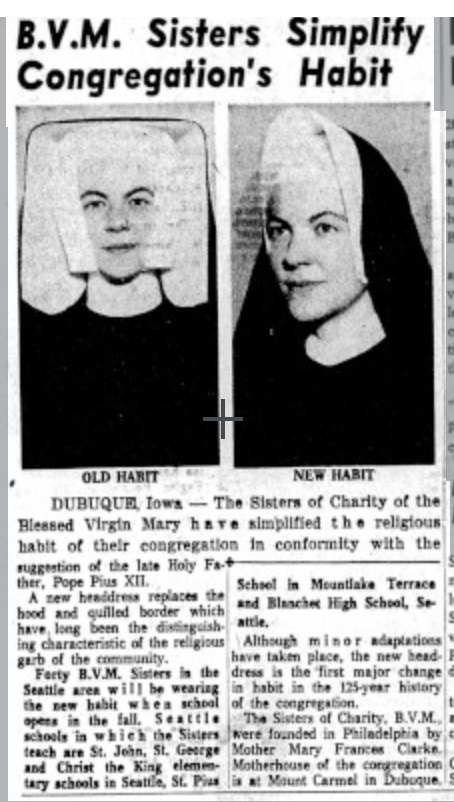

For more than a century, the habit worn by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (the BVMs) remained the same, and their cornette (headdress) was unmistakable. A brimmed hood extended in front of each sister’s face, creating blinders. Within the perfect right angles of the veiled hood, each face was framed—and obscured—by a horseshoe-shaped cap. The distinctive style has been described as a covered wagon, a Conestoga wagon, a cigar box, and more ominously, a coffin.

When Patricia Mary Jane Gallagher first saw the BVM habit as a transfer student to Mundelein College in 1942, she was dismayed. She and her mother had departed Iowa one July day on a train called The Land of Corn and by the time they walked up the Skyscraper building to ring the doorbell, their dresses were wrinkled in the humid air [1]. A nun greeted them with “all smiles,” but in Gallagher’s “dream of living in Chicago” she didn’t envision sisters wearing the same habit they wore at the college where she was dissatisfied for two years—Clarke College in Dubuque. “Another fantasy diminished,” she later wrote [2].

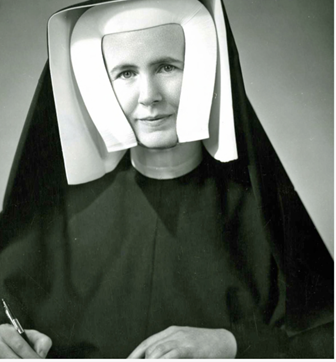

Yet after graduating from Mundelein College, Gallagher decided to enter the BVM religious order. Renamed Sr. Blanche Marie Gallagher, she was clothed in the same habit and headdress that once provoked her disdain. Later, her darkly humorous ode to the uniform garb indicates that her sentiments did not diminish, even when her vows required her to wear the habit:

Sisters wore ankle-length habits of black serge with a very complex and time-consuming headdress consisting of a heavily starched “quilled border” (derived from a nineteenth-century dust cap) under a heavily starched “hood” (originally a sunbonnet). The hood folded into a box at the back. Over this, a hip-length black veil was pinned into the shape of an Irish coffin—a very heavy symbol! We wore our coffins all day, every day [3].

Sr. Joan Frances Crowley, BVM, born in 1919, said that her artistic mother sketched and designed dresses for friends. “When my mother saw the habit and realized I was going to wear it, she cried. It was the most ugly thing she had ever seen” [4]. Boys called the sisters “the covered wagons” and Sr. Crowley said it did, indeed, look “like a Conestoga wagon” [5]. Her father told her superiors he didn’t feel bad to see his daughter in the habit because he knew she wouldn’t stay in the religious order. “I was too lively,” she said. [6] But Crowley stayed. Clothed in the complex habit, she went on to become a professor of history, a Fulbright scholar to Russia, and a published author.

When Sr. Mary Francine Gould, BVM, joined the religious order in 1929, she struggled to don the habit properly—a deficiency that her superior, Mother Isabella, noted. Once, when Sr. Gould was still a novice, she greeted Mother Isabella in the dining room. The elder nun replied, “They’ll never accuse you of being vain, dear” [7]. “I never was really right in the habit,” Sr. Gould said. “I never really got things the way they should be and so I was relieved to change” [8].

Change finally arrived during Vatican II. When the Church reformed, the habits of religious congregations modernized. The newly simplified habit was newsworthy and marked the first substantial change to the BVM habit in 125 years. Their new veil arched above the head and fell along their cheeks, framing and not covering their faces.

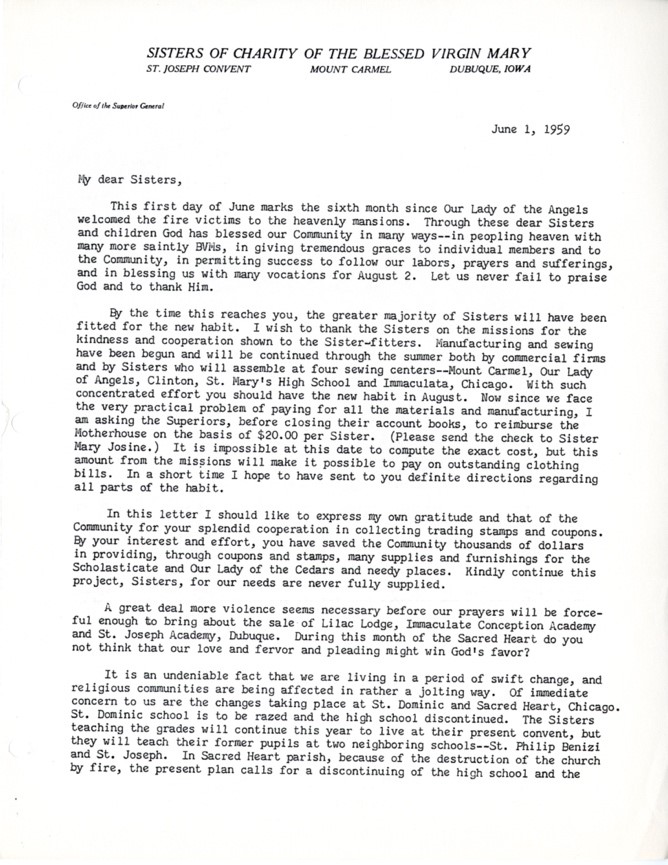

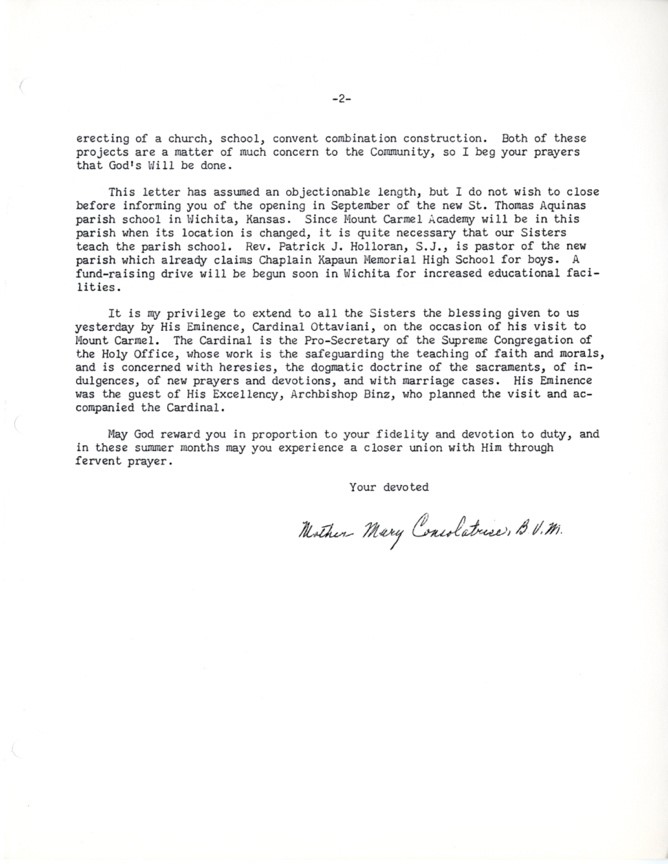

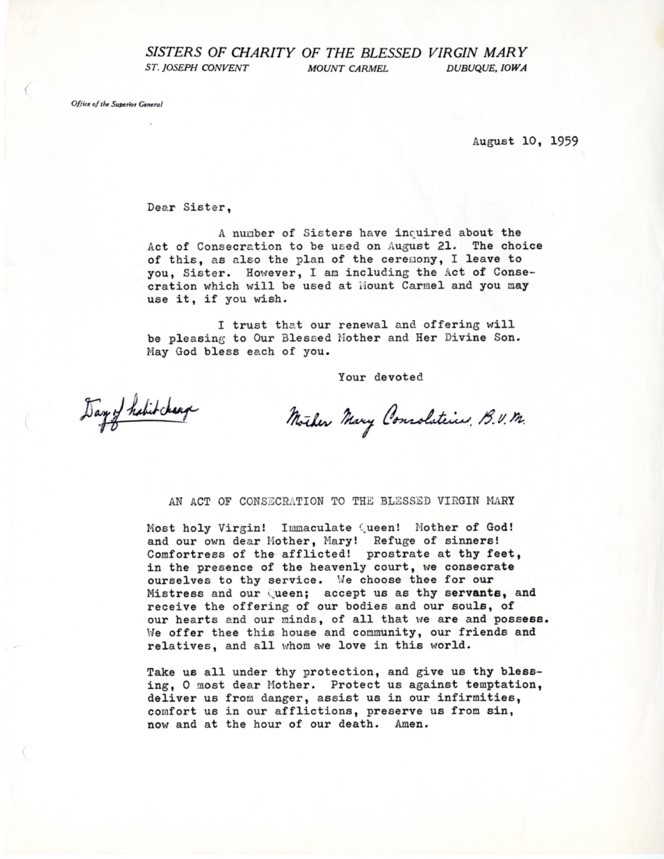

In a letter to all BVM communities on June 1, 1959, Mother Mary Consolatrice, BVM, addressed the new habit, the mammoth process of reclothing all the BVM sisters, and the era of upheaval. “It is an undeniable fact that we are living in a period of swift change, and religious communities are being affected in rather a jolting way,” she wrote [9]. By the time her letter would arrive, she wrote, most of the sisters had already been “fitted for the new habit” [10]. She assured the communities that their new habits would be ready by the August 21, 1959 consecration day. Commercial firms had been retained and sisters had been sewing at four sites in Iowa and Chicago for several months. Citing the “very practical problem of paying for all the materials and manufacturing,” Mother Mary Consolatrice instructed each community to repay the motherhouse $20 per habit [11]. A few months later, she wrote and share the text that would be spoken at Mount Carmel, the motherhouse, to consecrate the habits.

Staff and students took note of the new headdress and habit. “Change was everywhere,” wrote Norbert Hruby, vice president for institutional development at Mundelein College. “Gone were the cigar-box headdress and the black gabardine sheath” [13]. In another reflection also written decades later, Sr. Ann M. Harrington, BVM, conferred powers on the habit, allowing teachers to model to their female students that “our horizons as women were limitless” and “women could do anything they set out to do” [14]. “One question keeps returning to me. … What if we had not been in the habit? … Certainly our presence in classes and the halls of Mundelein would not have stood out as it did” [15].

Indeed, Hruby witnessed and documented student confusion when, a few years after the habit revisions, the BVMs could either wear a modified habit or to stop wearing a habit altogether.

So it was that on the first day of the fall semester in 1965, when the students returned to campus, they were met by faculty women who looked familiar, but so different. The students would address their professors, ‘Sister?’ hoping they got it right. (Several Jewish and Protestant women on the faculty took to wearing tags, stating simply, ‘I am not a sister!’ These changes were more than symbolic [16].

For Sr. Ann M. Harrington, BVM, discarding the habit “freed us as women to recognize our own individuality” [17]. But it also made the religious women the target of vitriol. In an oral history interview, Sr. Mary DeCock recalled that when lay women saw the religious sisters choose to not wear a habit and “choose to do what they wanted to do,” she felt their anger. “I don’t know if they thought we were going after their husbands or what,” Sr. DeCock said. “If we changed and became more like them it unbalanced them a little bit. … We had stepped out of our role. And when we stepped out of our role, what did that do to theirs?” [18] During that same time, sisters could also return to their given names and their family names, and opt not to be called by a title and their assigned religious name. This enraged clergy, DeCock said. One pastor expressed his frustration at needing to learn the women’s names. Before, he admitted, he could visit a convent and greet anyone as “sister” and “it didn’t make a difference who they were” [19]

The six years from 1959 to 1965 introduced more change to the BVMs than any of the previous 125 years. Before the habit disappeared, it had seemed to be the subject of widespread ambivalence, by the sisters who grappled with its complexity daily as well as those who considered it a symbol of the Catholic Church and faith, itself. With the habit gone, students and parishioners were left to reflect—or simply react—while the religious sisters worked to forge their own paths as educators and agitators, as symbols of convention and revolution.

Abbie is a PhD student in US and Public History at Loyola University Chicago. She has an MFA in visual arts from the University of Chicago and an MFA in creative nonfiction from the University of California, Riverside. Abbie is the author of Dedicated to God: An Oral History of Cloistered Nuns (Oxford University Press, 2014) and documentary filmmaker of the 2017 collaborative film, Chosen (Custody of the Eyes), which forms a portrait of a young woman in the process of becoming a Poor Clare Colettine nun.

Citations

[1] Blanche Marie Gallagher, BVM, “Life Flows Through the Dream,” in Mundelein Voices: The Women’s College Experience, 1930-1991, ed. Ann M. Harrington and Prudence Moylan (Chicago: Loyola Press, 2001), 75.

[2] Gallagher, “Life Flows Through the Dream,” 75.

[3] Ibid., 83.

[4] Sr. Joan Frances Crowley, BVM, transcript of an oral history conducted on November 16, 1998 by Lisa Oppenheim for Mundelein College Oral History Project, Voices from Mundelein, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago, 5.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Sr. Mary Francine Gould, BVM, transcript of an oral history conducted on June 10, 1999 by Mary DeCock, BVM, for Mundelein College Oral History Project, Voices from Mundelein, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago, 14.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Mother Mary Consolatrice letter dated August 10, 1959. Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Mundelein College Records. BVM Reference Collection. Box 5. Folder D. Community Correspondence.

[10] Ibid.

[10] Mother Mary Consolatrice letter to the BVM congregations dated June 1, 1959.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Norbert Hruby, “The Golden Age of Mundelein College: A Memoir, 1962-1969,” in Mundelein Voices: The Women’s College Experience, 1930-1991, ed. Ann M. Harrington and Prudence Moylan (Chicago: Loyola Press, 2001), 185.

[14] Harrington, “A Class Apart: BVM Sister Students at Mundelein College, 1957-1971,” page 139.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Norbert Hruby, “The Golden Age of Mundelein College: A Memoir, 1962-1969,” in Mundelein Voices: The Women’s College Experience, 1930-1991, ed. Ann M. Harrington and Prudence Moylan (Chicago: Loyola Press, 2001), 185.

[17] Sr. Ann M. Harrington, BVM, “A Class Apart: BVM Sister Students at Mundelein College, 1957-1971” in Mundelein Voices: The Women’s College Experience, 1930-1991, ed. Ann M. Harrington and Prudence Moylan (Chicago: Loyola Press, 2001), 139.

[18] Sr. Mary DeCock, BVM, transcript of an oral history conducted on November 3, 1998 by David B. Cholewiak for Mundelein College Oral History Project, Voices from Mundelein, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago, 8.

[19] Ibid.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.Questions? Please contact the WLA at wlarchives@LUC.edu.