This post is part of the WLA blog’s 2022 series written by guest writers. These writers are graduate students in the Public History program at Loyola University Chicago. Each visited the archives during Fall 2021, delved into the collections, and wrote about a topic not yet explored here. We are excited to share their research and perspectives!

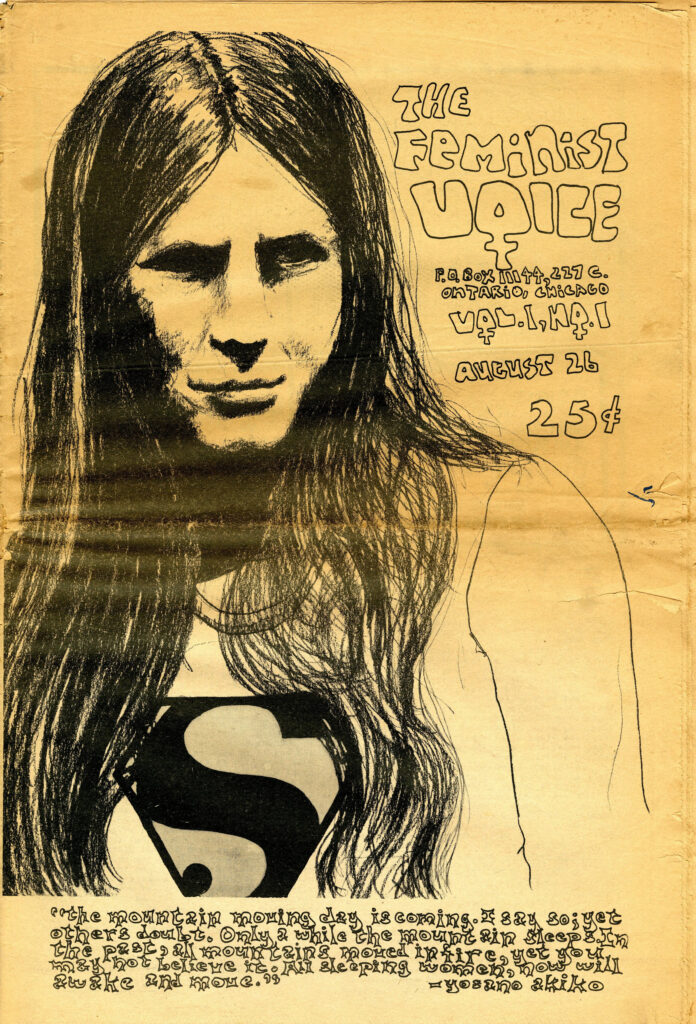

On August 26, 1971, The Feminist Voice, a magazine “published in the interest of women” was first released in Chicago. Four years earlier, in 1967, the first “new feminist,” later known as “second wave feminist,” group in the United States was formed and released a regular newsletter, Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement. It was from this Chicago Women’s Liberation Union newsletter that The Feminist Voice drew inspiration to report on the rise of new feminism in Chicago and the larger nation. The date of the first issue, August 26th, was of key importance to the writers of the magazine as it was the anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment which recognized women’s suffrage nationally, a victory that inspired Second Wave Feminists.[1]

The Feminist Voice collective was composed of a diverse group of women; married women, divorced women, women with and without children, lesbian and heterosexual women, politically organized women, and “loners” [2]. While they shared little philosophically, the collective shared a few key beliefs that the magazine would be used to address. The first editorial column published in The Feminist Voice made their central cause clear: “We know that the liberation of all women must become women’s number one priority. We will not be talked into fighting for another’s cause as our sisters in the 1920s and 1960s were when they fought for the civil rights of other people. We have learned that fighting for the rights of others keeps us from facing our own oppression. We believe that people must free themselves from forces that oppress them [3].” The Feminist Voice would serve as a place for these women to express their “reasoned rage” in alternative to the “male-dominated press” and a space for self-discovery [4].

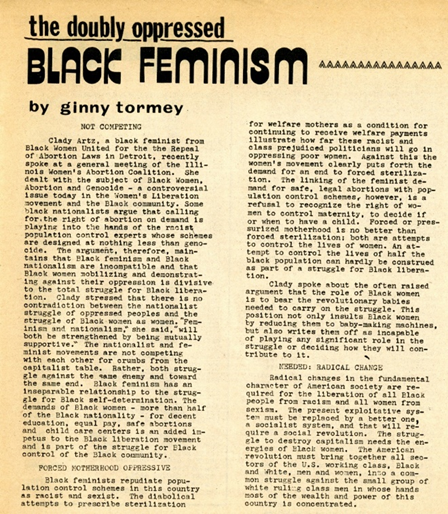

Over the course of its publication, The Feminist Voice covered a variety of taboo topics including abortion, vasectomy, pregnancy, women’s history, and racism. Lesbianism and safety and self-defense for women also had recurring places within the pages of The Feminist Voice. Because of the topics they covered, and the absence of a central ideology, The Feminist Voice faced criticism for “being too literary, not literary enough, too political, to apolitical, too Marxist, too anti-Marxist [5].” Contrary to this criticism, The Feminist Voice collective planted its feet firmly within the politics of change, refusing to be complacent in their roles as feminists and women, constantly looking for avenues to grow personally, and as a society.

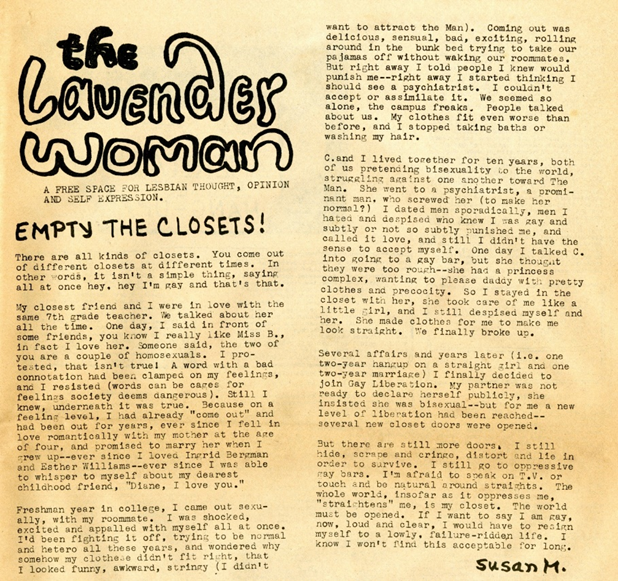

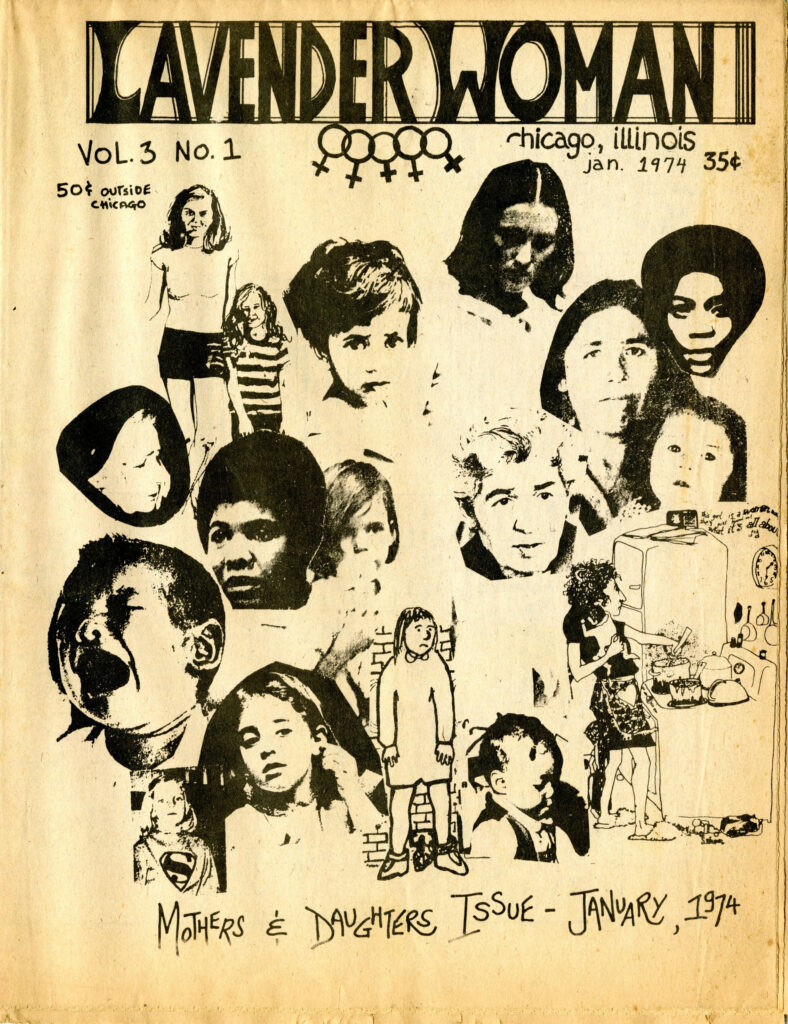

A regular section in early issues, typically located at the end toward the events calendar, was “The Lavender Women,” a monthly forum produced by members of the Gay Women’s Caucus. “The Lavender Women” provided the readership with “a free space for Lesbian thought, opinion and self expression [6].” After four months of publication, The Feminist Voice cut production of the column and Lavender Woman became a standalone publication in 1971. The collective behind Lavender Woman confronted issues such as Lesbian pride, Lesbian parenthood, faith, lesbian interactions with gay men, and identity in Chicago in the 1970s. Lavender Woman remained in print for five years, until 1976.

Throughout its publication, The Feminist Voice, and its spin-off publication Lavender Woman, served as an avenue for feminists in Chicago to speak truth to power. The Feminist Voice allowed for expression of feminist rage, thought, creativity, and self-expression and allowed for these expressions to be utilized to fight for change. From the first editorial, The Feminist Voice collective made their goals for the paper clear: “Our newspaper will use the abundant talent of women to support other women in the women’s movement, to help create women’s history, straight from the viewpoints of women, getting down the events of what will be one of the great revolutions in the history of Western Civilization [7].” In this, The Feminist Voice prophesized its legacy and place in the collections of the Women and Leadership Archives. The Feminist Voice, held in the Connie Kiosse collection at the WLA, offers much insight into new feminism and what it stood for.

Chris is a graduate assistant at the WLA and is in their second year in the Public History MA program at Loyola. Chris focuses on Queer history in America and Germany in the pre-Stonewall era. In their free time, Chris is a baker, drag queen, and dog parent.

[1] “Editorial” The Feminist Voice vol 1. no. 1, 25 August 1971. Box 2, Folder 4,Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

[2] “Editorial,” The Feminist Voice vol 1. no. 1, 25 August 1971. Box 2, Folder 4, Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Editorial,” The Feminist Voice vol 1. no. 6, March 1972. Box 2, Folder 4, Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

[6] “The Lavender Women,” The Feminist Voice vol 1. no. 2, September 1971. Box 2, Folder 7, Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

[7] “Editorial” The Feminist Voice vol 1. no. 1, 25 August 1971. Box 2, Folder 4,Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Images:

Figure 1. Cover page of The Feminist Voice vol 1. no, 1 August 1971. Box 2, Folder 4,Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Figure 2. “Black Feminism,” The Feminist Voice vol 1. no. 6, March 1972. Box 2, Folder 4,Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Figure 3. “The Lavender Women,” The Feminist Voice vol 1. no. 2, September 1971. Box 2, Folder 4, Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Figure 4. Lavender Woman vol. 3 no. 1, September 1971. Box 2, Folder 7, Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Figure 5.“Advertisement: Liberated Woman” The Feminist Voice vol 1. no, 1 August 1971. Box 2, Folder 4,Connie Kiosse Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed. Questions? Please contact the WLA at wlarchives@LUC.edu.