When exploring the Edgewater neighborhood on Chicago’s north side, one would have a hard time failing to notice the Broadway Armory. This ornate, gigantic structure—first built as an ice-skating rink in 1916—takes up an entire city block. Repurposed as an armory in response to WWI and race riots in Chicago, by the 1970s and 80s the building was falling apart and barely used. What was to become of this gigantic building?

Local, state, and national players put their differences aside to collaborate and create a vital community resource out of this dilapidated structure—the Broadway Armory Park. One of Chicago’s first female aldermen, the 48th Ward’s Marion Volini, played a key role in rehabilitating the Broadway Armory into an indoor recreation center. Government records, correspondence, photographs, and news clippings found in the Marion Kennedy Volini Papers—housed here at the Women and Leadership Archives—tell the story of how this one-of-a-kind community center came to be.

The Chicago Arena

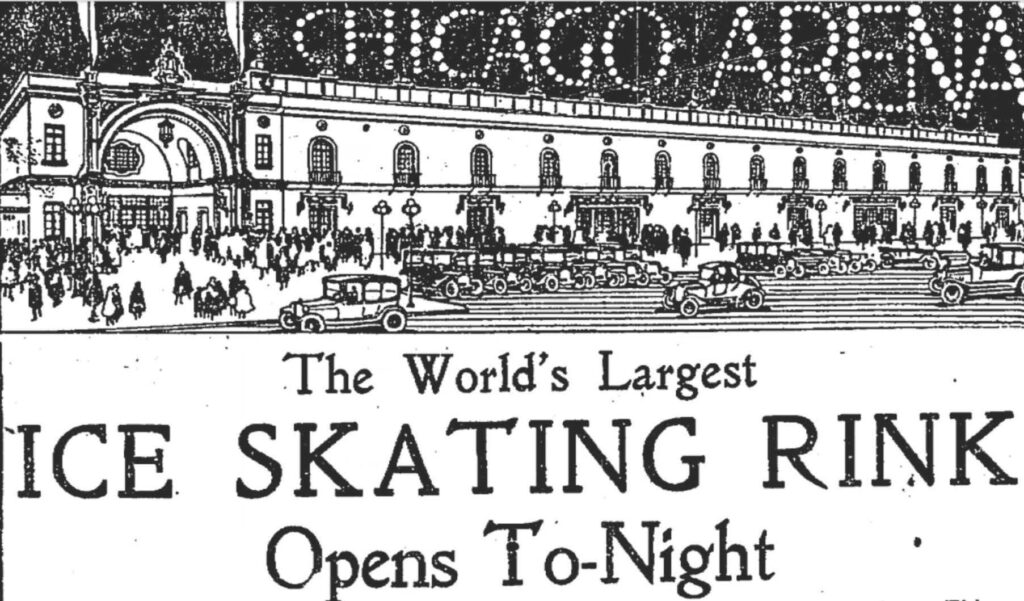

Even though the structure at 5917 N. Broadway served as an armory for decades, it was not designed as such. In fact, the Chicago Arena, not to be confused with the Chicago Stadium, originated with a starkly different purpose—an ice-skating rink. During the early twentieth century, skating was an increasingly popular pastime, driven in part by ice companies seeking profit in winter months when business was slow. Built by the Wood-Springer Company in 1916, the Chicago Arena—marketed as “Chicago’s great inland lake”—was part of this new fadi.

The Arena proved to be a hit with the public, with the Tribune reporting that Chicago was deep “in the grip of ice skating.”ii Patrons happily skated while listening to live music performances, before retiring to balcony dining rooms “as cozy as your library.”iii However, the joy would soon subside; a month after its opening, the United States entered WWI, and skating seemed a rather frivolous activity for a nation at war. The Chicago Arena closed as a skating rink in 1919—but would not lie dormant for long.

1919’s ‘Red Summer’: The Inception of the Broadway Armory

On July 27, 1919, 17-year-old Eugene Williams was swimming in Lake Michigan at the 29th Street Beach on a hot summer day. Eugene, who was Black, accidentally crossed an imaginary color line, drifting into the white section of the water. Whites on the beach began stoning him, striking him on the head and leading him to drown. Over the next week, the city erupted in violence. White mobs invaded Black neighborhoods, attacking civilians and burning houses down. The Illinois National Guard was sent in to restore order and protect property, but not before 38 people were killed, and hundreds more injured.

Part of the larger ‘Red Summer’ of labor and racial violence taking place in American cities, the riot played a large part in the creation of a new armory in Chicago: The Broadway Armory. In October 1919, the Tribune reported that Chicago Arena’s owners leased the building to U.S. War Department for use as an armory. At its dedication ceremony in February of 1920, Illinois Governor Frank Lowden acknowledged the National Guard’s role in Chicago, praising their valor “on the south side during the race riots.”iv

Learn more about the Chicago race riots of 1919

Broadway Armory Park

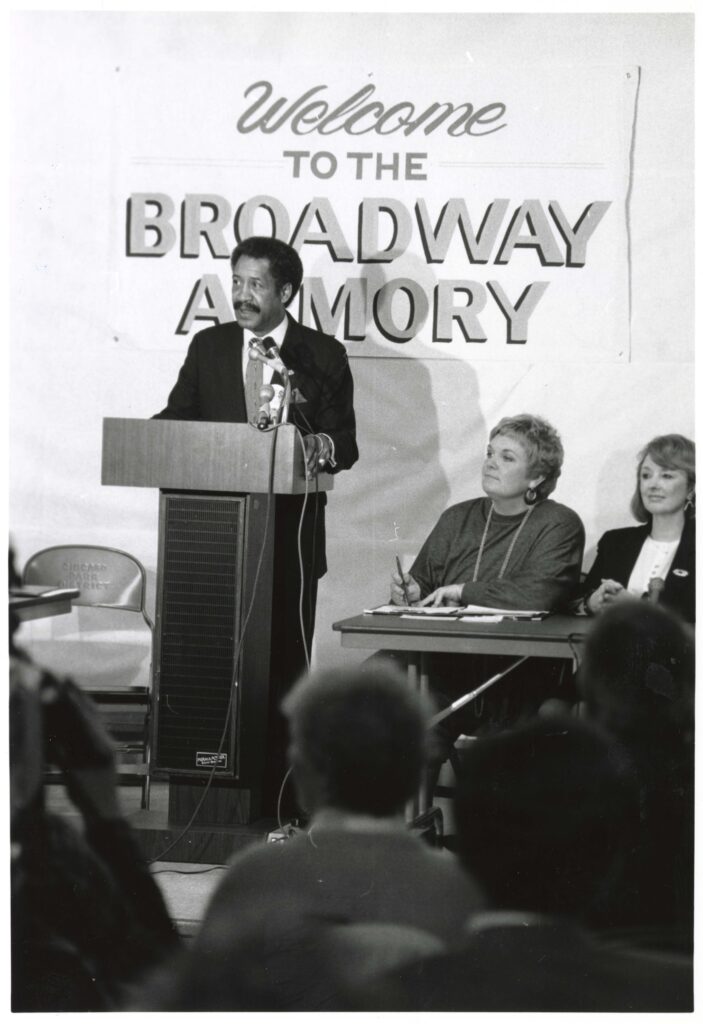

Throughout the mid-twentieth century, the National Guard used the Broadway Armory only for a few hours per month, leading the historic building to deteriorate. Beginning in the 1970s, community leaders advocated for the building to be repurposed into a recreation center—especially considering the Edgewater neighborhood lacked any city parks. Kathy Osterman, who later joined the city council, spearheaded the years-long effort, starting during her time in the Edgewater Community Council (ECC). Osterman described the community’s efforts as “a very complex operation,” involving a myriad of players across government.v

In a letter to Ald. Volini, the ECC succinctly stated the case for the park, arguing that:

“The Broadway Armory will have tremendous importance in renewing community spirit in Edgewater and in giving our children and senior citizens recreational opportunities they have never had in their neighborhood.”vi

The community’s hard work paid off. In 1979, the Chicago Park District signed a 25-year lease with the National Guard to use the armory as a recreation center.

More than $2 million of local, state, and federal money was spent rehabbing the building, putting in a new roof and hardwood floors. Residents’ hopes and ideas for the park were compiled by Loyola professor Homer Johnson in a comprehensive recreational needs assessment. This exhaustive survey of the community—seeking input from children and senior citizens—drove decision making and ensured the space would be used often by the public. For her part, Ald. Volini was instrumental in securing the city council’s support for the project. Volini helped create the Broadway Armory advisory board, a group made up of community members tasked to manage the park. She also locked in funding from the city to construct parking lots adjacent to the armory, further increasing its access.

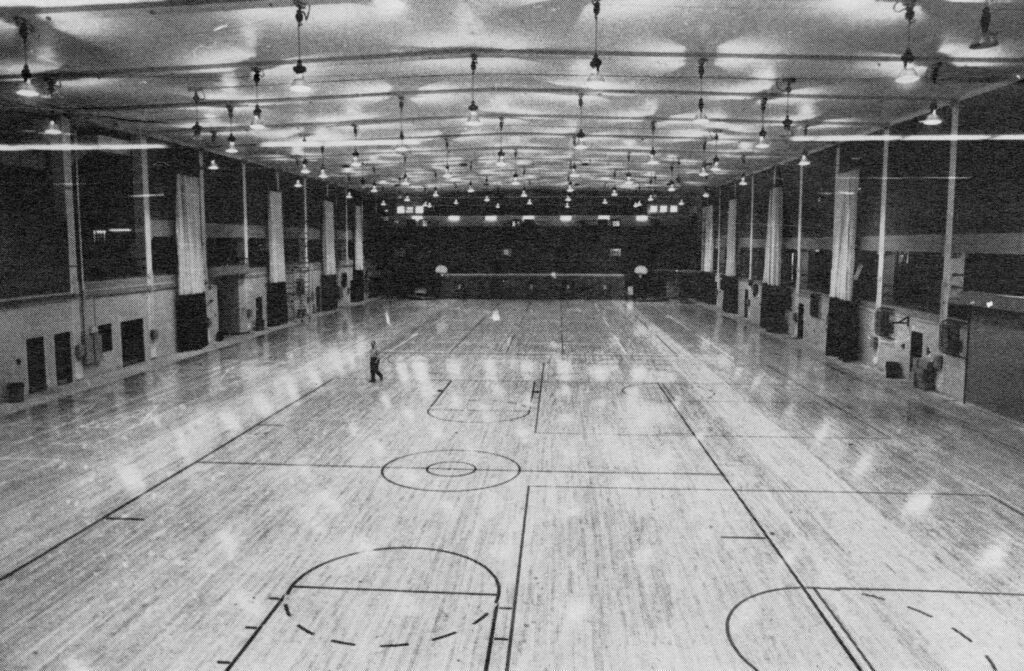

Once the park opened to the public on April 1, 1985, countless recreation, art, and community building activities were now available to the Edgewater community. According to Ald. Volini, “The Armory has emerged as a tremendous asset to the neighborhood.”vii Schools were invited to tour the new recreation center, as were block clubs, condo associations, and youth groups. An estimated 1,000 community members used the park every day. The building contains 100,000 square feet of recreation space, including a huge gymnasium, art rooms, a stained-glass studio, a workout room, a woodshop, meeting rooms, and a fully equipped photography lab. Popular activities included basketball, volleyball, track and field, fitness classes, dancing, gymnastics, ballet.

Conclusion

The Broadway Armory Park remains a beloved resource in the Edgewater community. In fact, in the late 1990s, residents made clear their passion for the park. When the city made moves to demolish the building for a parking lot, the community came together in protest. Their advocacy for protecting the park paid off: the city officially purchased the property from the Illinois National Guard in 1998, transferring ownership to the Chicago Park District. In the end, Ald. Volini was spot-on when she pointed to what made the project so successful: “The key to a well-run facility is community involvement.”viii Luckily, the park continues to flourish today, providing the setting for countless recreational and community activities.

Willow is a Graduate Assistant at the Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). They are in the final year of Loyola University Chicago’s M.A. in Public History degree program. In their spare time, they are a stained-glass artist who designs windows and lampshades. For more information about this post, contact wlarchives@luc.edu.