According to the National Center for Education Statistics, as of 2016, 44% of full time college faculty were women. While we still have a long way to go to create an academic culture that is free of discrimination and sexism, it is important to appreciate how far we have come. Eleanor F. Dolan’s Papers gives us a glimpse into the struggle women across the country endured while trying to become faculty members in the 1960s.

Eleanor F. Dolan was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1907. After receiving her B.A. from Wellesley College and her M.A. and Ph.D. from Radcliffe College, she started a long career focused on women’s rights and higher education. After being a professor 12 years, Dr. Dolan joined the staff of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) as a specialist for higher education. In 1967 she joined the federal government as a Specialist for Graduate Academic Programs in the Bureau of Higher Education. She was executive secretary of the national Council of Administrative Women in Education, participated in many local organizations, and was a founder of the Women’s Equity Action League.

While Dolan was a part of the AAUW from 1950 to 1967, the organization focused on women and graduate school. With the increase of students (women and men alike) going to college in the 1950s, the organization wanted to support the education of more faculty members. Their College Faculty Program, started in 1959, gave women financial assistance to pursue higher education and future careers in professorship. Specifically for “mature women” (those 35 or over) looking to be full time students, the program gave scholarship winners one to three full years of tuition.

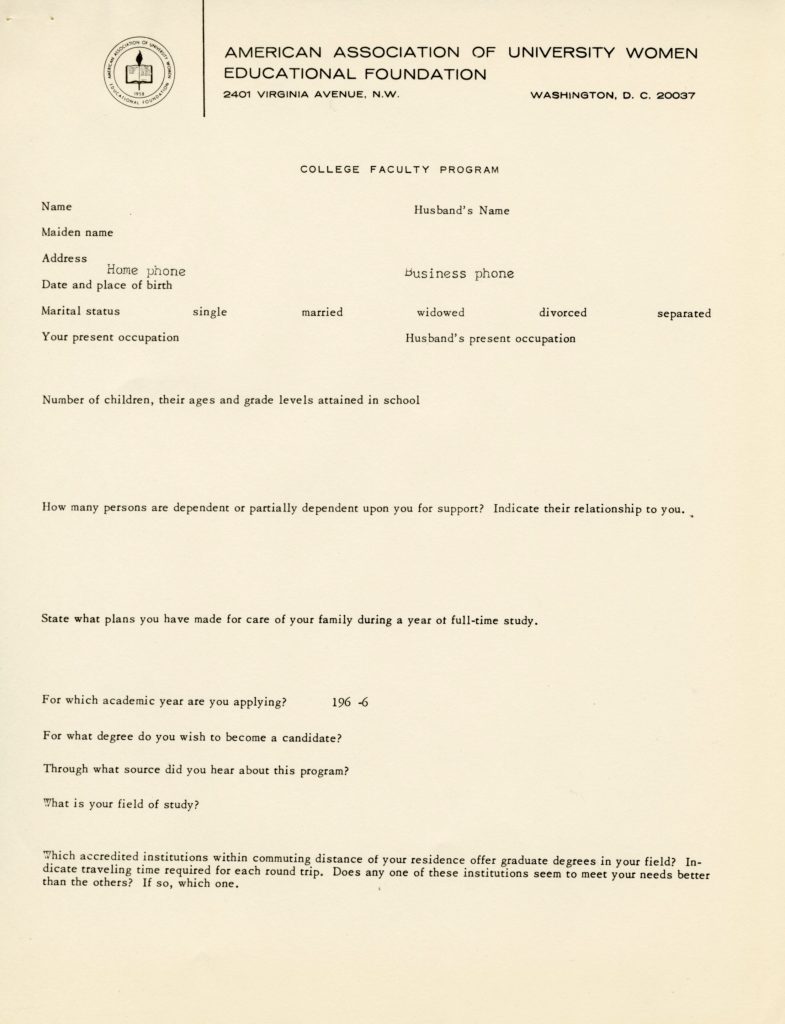

The goals and mission of the College Faculty Program

The folders containing the information on the AAUW and the College Faculty Program offer only a glimpse into the over 100 women’s lives that were changed with this program:

One participant “expressed her delight to ‘find that she is capable of productive mental life though over 50,’” while another suggested that “you continue this wonderful program and encourage others to further their education.”

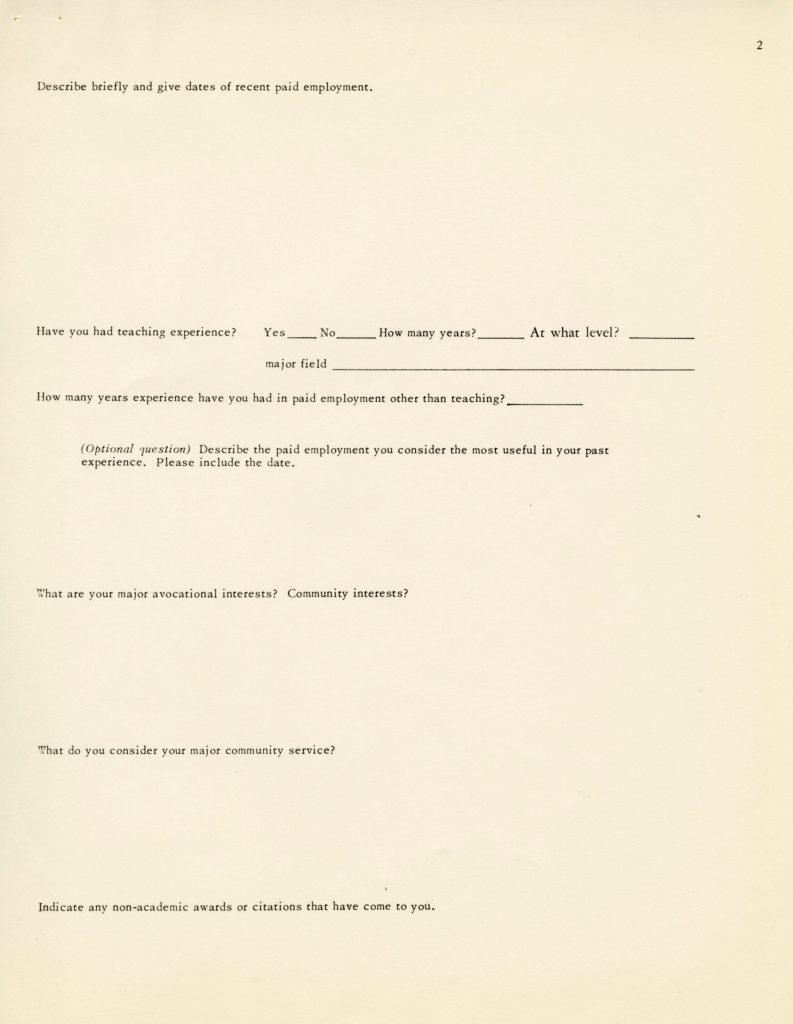

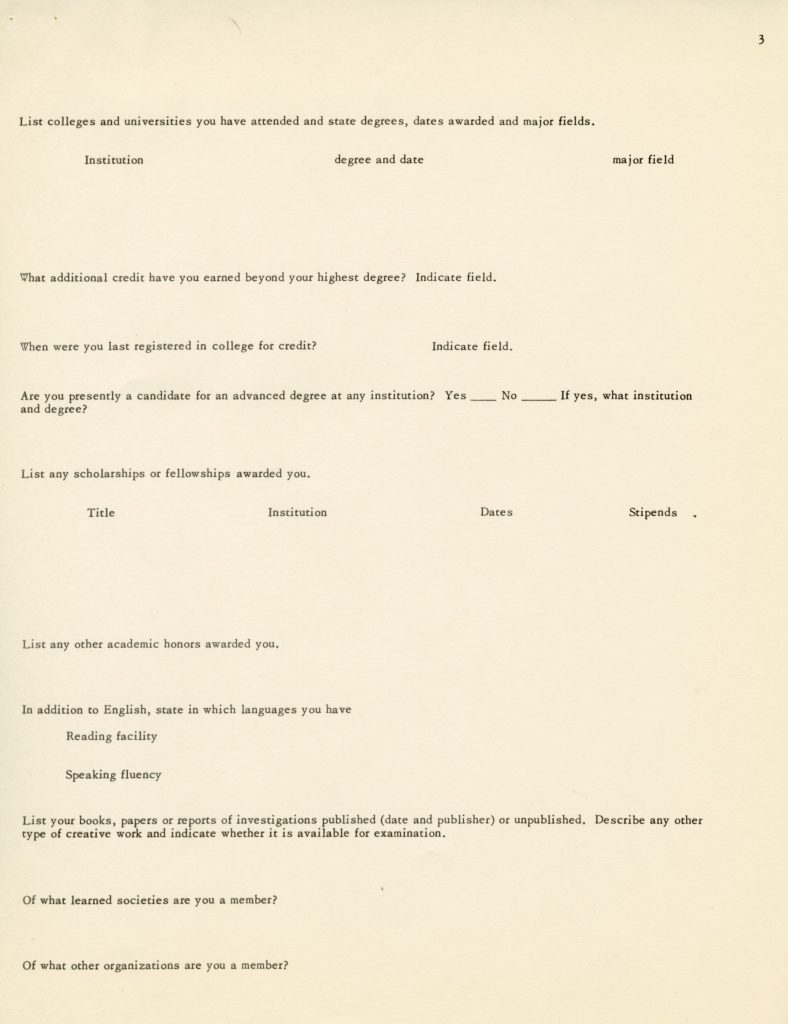

However, beside the glowing reviews and reports of straight A’s, the documents reflect the obstacles women (especially ‘older’ women) faced when considering higher education instead of being traditional homemakers. Here’s a sample application form:

As you can see in the scholarship application, questions about husband’s occupation, ages of children, and the plans about the family are prioritized on page 1, while page 2 and 3 ask about the woman’s personal achievements and interests. The health statement page of the application focuses on their physical ability to carry on a full year’s educational program, especially in her ‘old’ age of 35.

This application offers two different points of view- 1. The view of the AAUW, who want to find applicants who are fit enough to finish the program, and 2. The view of the applicants, who, through the questionnaire, are being encouraged to think first about what their educational journey will mean for their family and then if they are prepared to become faculty members. I wonder if men were ever asked about how their educational careers affect their family.

Scholarship winners’ testimonies also describe the difficulties of being responsible for taking care of the home on top of being a full-time student, and the feelings that come with restarting school after some time away.

Beyond giving money to students, the program also conducted surveys asking universities and colleges about their opinions and policies regarding admission, financial aid, counseling, and employment for ‘mature women’. This shows how focused the AAUW was in fighting institutional sexism and discrimination, along with the importance of offering a variety of masters degrees, and encouraging them to accept more women who are older than the typical candidate. The 44% of women employed as faculty members could thank the AAUW for pressuring universities to think about how their policies fought against women in academia, and could thank the women in the College Faculty program for showing that they can be dedicated, amazing graduate students while still being women.

Emily is a Graduate Assistant at the WLA and is in her second year in the joint Public History/Library Information Science program with Loyola University Chicago and Dominican University. She enjoys going on long walks with her puppy, visiting cool museums, and cheering on the White Sox during baseball season.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.