In 1920, the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote was ratified by the 34th state and became part of the United States Constitution.[i] Suffragists had won this battle, but the war for equality was far from over. Within a year of winning the right to vote, women’s rights activists found their next battle in the idea for “a federal guarantee that the law would treat people equally regardless of their sex” (Thulin, 2019).[ii] From this idea came the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Though it was introduced early on, the ERA did not gain traction until the 1960s-1970s. This last draft of this Amendment is short and simple:

Section 1. Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Section 3. This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification.

The ERA inspired controversy. One group that opposed it, called Stop Taking Our Privileges (STOP) ERA, claimed the ERA took away women’s privileges as homemakers and would rob them of their femininity. To fight this claim, a new group called HERA (Homemakers for the Equal Rights Amendment) was formed.

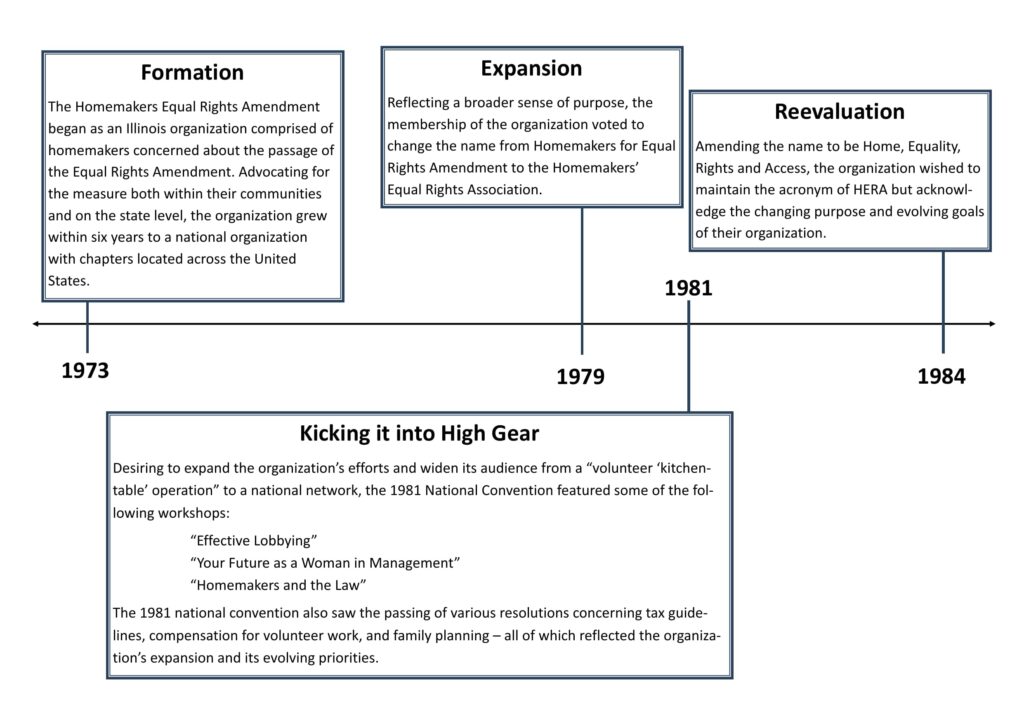

HERA began in Illinois and soon gained a national base, with organizations throughout the United States. Over the long fight for the ERA, their name changed a few times to reflect shifting goals, but always kept the HERA acronym. HERA’s tactics included writing letters to government officials, holding marches and rallies, and lobbying. For a summary of HERA’s timeline, see Figure 1.

Timeline of HERA from a Women and Leadership Archive Exhibit.

A 2015 WLA blog post takes a deeper look at HERA’s history and activist efforts, and – to avoid reinventing the wheel – this post is going to focus on specific items from the Women and Leadership Archives HERA’s collection. The items featured include instructions on lobbying politicians, a rally flier, songs adapted for HERA, photographs, symbols, and political cartoons.

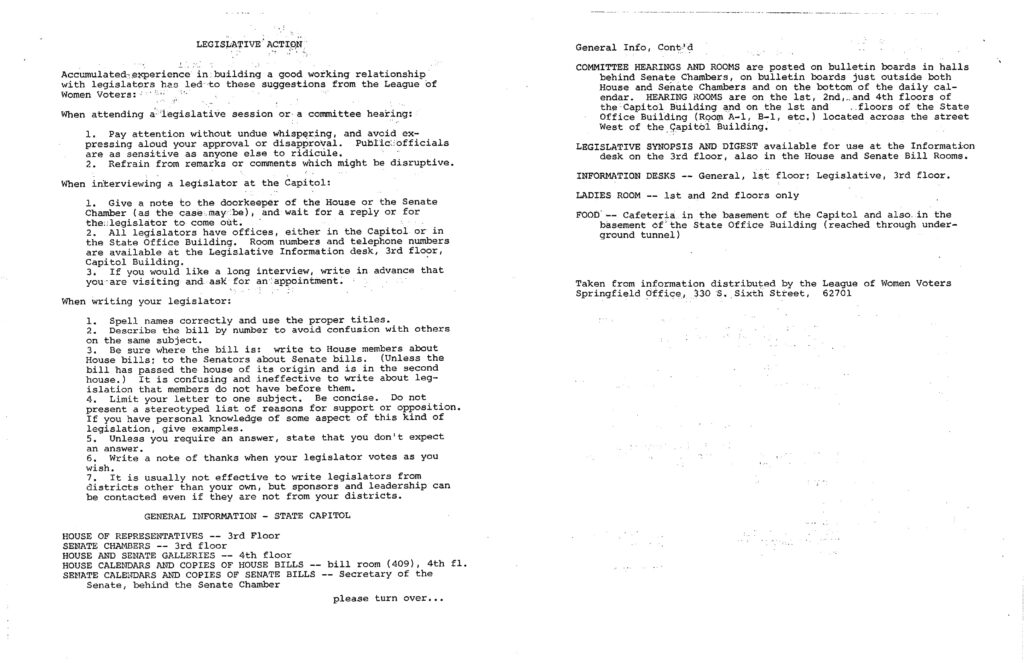

Figure 2 is a piece of literature handed out to HERA members – guidelines for lobbying. HERA focused a great deal of effort on lobbying including writing letters to representatives and gathering at government buildings. Their guidelines show how they gathered advice on proper lobbying tactics and sought to win politicians over to their side.

Legislative Action hand-out, Box 2, Folder 4, Homemakers’ Equal Rights Association Records, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University.

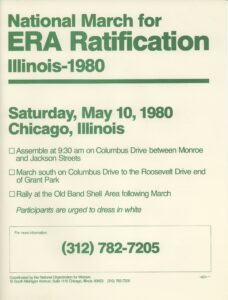

Figure 3 is a poster from a 1980 ERA Ratification rally attended by HERA members. The poster urges marchers to dress in white, a symbolic connection to the white clothes adopted by suffragists almost a century earlier.

Flyer for National ERA March, Box 3, Folder 1, Homemakers’ Equal Rights Association, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

HERA’s leaders also created and rewrote songs for their fight. The audio files below, recreations of HERA rally songs by WLA staff for this blog post, are two examples of songs used at rallies, conventions, and other gatherings to voice their support for the ERA’s promise of “dignity of every human soul.”

Lyrics modified by HERA sung by Sesquicentennial Scholar Scarlett Andes.

Lyrics: Put women in the Constitution! / Put women in the Constitution! / Put women in the Constitution! / We must have ERA! / Glory, Glory, Hallelujah! / Glory, Glory, Hallelujah! / Glory, Glory, Hallelujah! / We must have ERA!

Lyrics modified by HERA sung by Sesquicentennial Scholar, Scarlett Andes.

Lyrics: O beautiful for dignity / of every human soul / And under law, equality / the universal goal / America, America, / God help thy people see / that equal worth for all on earth / is thy security.

Opposing groups like STOP ERA, tried to discredit the ERA by stating it would strip mothers and homemakers of their rights. HERA decided to combat this ideology by including children in their efforts. They took their children to visit politicians, showing that homemakers were not losing their rights. By bringing children into their activities, HERA members demonstrated that women could still be homemakers and pursue traditional roles of motherhood and femininity even if the ERA was passed. In fact, many HERA members supported the ERA as a measure to make homemaking a valid and dignified career choice.

Photograph of HERA meeting with the Illinois Governor in 1982, Box 3, Folder 7, Homemakers’ Equal Rights Association Records, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

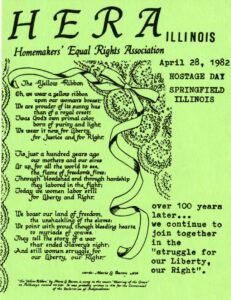

Two common symbols appear in the HERA collection at the WLA: a rose and a yellow ribbon. The rose, Figure 5, was HERA’s logo and appears on official documents. The yellow ribbon, Figure 6, was used for Hostage Day ceremonies and worn “for Liberty, for Justice, and for Right.” Hostage Day was a HERA demonstration that criticized state legislators for ‘holding women hostage’ by refusing to ratify the ERA, as explained in this flyer’s poem.

Rose Logo for HERA, Homemakers’ Equal Rights Association Records, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

Hostage Day Flyer 1982, Box 2, Folder 6, Homemakers’ Equal Rights Association Records, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

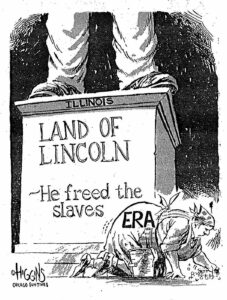

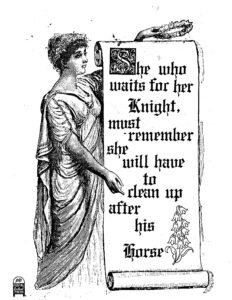

In their newsletters and newspaper ads, they even created political cartoons! Messages in these cartoons ranged from finding men who supported the ERA to implying hypocrisy in local governments. Below are examples of each: cautioning women in what they look for in a man; and reminding Illinois Lincoln freed the land but women do not have some rights.

ERA political cartoon in the Chicago Sun-Times, Homemakers’ Equal Rights Association Records, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

ERA related political cartoon, Homemakers’ Equal Rights Association Records, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

Despite their efforts, the 1982 deadline for the ERA passed without enough states’ approval to become a Constitutional Amendment. HERA changed names once again to Home, Equality, Rights and Access to reflect their evolving goals. HERA dissolved in the late 80s or early 90s and donated their materials to the Women and Leadership Archives in 1994.Researching HERA really opened my eyes to the continuing struggle women’s rights faced. In the beginning of 2020, Virginia became the 38th state to ratify the ERA. However, there is a great deal of debate about whether it can still become part of the Constitution. Looking at HERA’s efforts inspires me to continue to advocate for what I believe in.

Miranda is a graduate assistant at the Women and Leadership Archives. She is a second year Public History Master’s student. Her dream job is work in a museum, possibly with collections. She enjoys studying dance history as well as 20th century social changes. In her free time, she looks for four-leaf clovers!

[i] The 19th Amendment broke a small boundary for women to vote, but the fight for women of color continued. For more information see https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/vote-not-all-women-gained-right-to-vote-in-1920/.

[ii] For information on the ERA, check out https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/equal-rights-amendment-96-years-old-and-still-not-part-constitution-heres-why-180973548/.