The May Crowning ceremony originated in the 16th century as a papal tradition and spread as a form of public veneration for the Blessed Virgin Mary until the mid-20th century, where it reached peak popularity in the United States.i The ritual was often celebrated in schools and parishes concurrently with Mother’s Day or First Communion ceremonies to celebrate the role of women in the Church.ii Young women were chosen from among their peers as most deserving of the honor of placing a crown of flowers atop a statue of Mary. The ‘May Queen’ and her attendants would dress in white and process around the campus or church grounds while other students, teachers, and parents gathered to watch and sing devotional hymns.

May Crowning ceremonies were celebrated at Mundelein College* from the early 1930s through the mid-1960s. A 1942 planning bulletin concludes, “Remember that Coronation is an act of RELIGIOUS HOMAGE… And be dressed becomingly”.iii While in some years, Mundelein College students elected the worthiest representative from their peers to serve as the May Queen and her attendants, other years the prefect of the Sodality Club, the school’s lay religious group, was given the honor automatically.

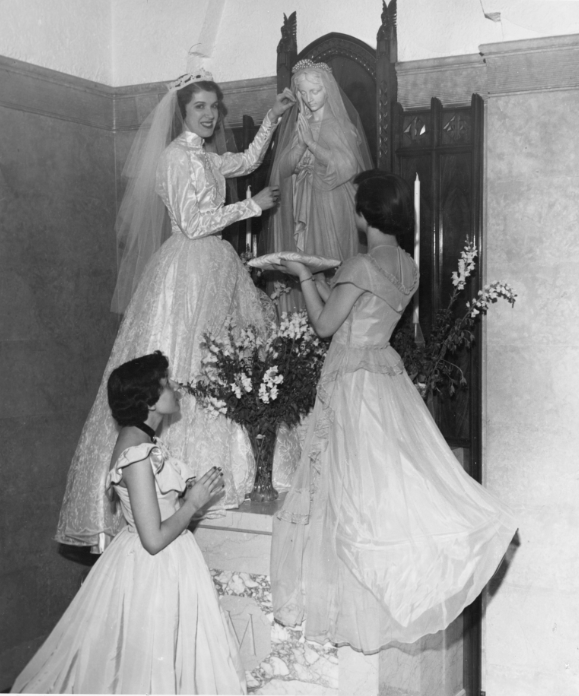

Students would process from the Skyscraper building to the steps of the library (later known as Piper Hall), with the May Queen and her attendants leading the procession, all wearing white or light-colored dresses, and the seniors processing behind them in graduation caps and gowns.iv In later years, the ceremony moved to the auditorium to eliminate possibly inclement weather.v

The celebration of the May Queen at Mundelein College exemplifies the conflict between American Catholic feminists and their relationship with the Church in the 20th century; while the ceremony celebrates women’s historical and contemporary contributions to Catholicism, it also relegates these contributions to traditional – and some may argue, outdated – gender roles. For example, the traditional logic behind choosing the May Queen is to select the loveliest eligible girl, a fact emphasized by Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s popular 1855 poem “The May Queen”:

[There’s] none so fair as little Alice in all the land, they say:

So I’m to be Queen o’ the May, mother, I’m to be Queen o’ the May.vi

The elevation of the May Queen above her peers could suggest that less than works of charity, justice, or kindness, morality and devotion for girls ought to be linked to their appearance. Historically, the role of women in the Catholic Church has been tightly linked to their ability as mothers or in relation to men. Marina Warner writes in Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary, that, through the Church’s adoration of Mary as an object of intercession, “The natural order for the female sex is ordained as motherhood… The idea that a woman might direct matters in her own right as an independent individual is not even entertained”.vii

However, another interpretation of the May Crowning gives young girls democratic agency in electing the best representative from amongst themselves. Arguably, the important role the ceremony played in 20th-century Catholic life brought Mary and lay women to the forefront of modern Catholicism. In his 1974 encyclical Marialis Cultis, amidst a new wave of Marian adoration, Pope Paul VI suggested an essential role for Mary in the Church, writing, “She shows forth the victory of hope over anguish, of fellowship over solitude, of peace over anxiety, of joy and beauty over boredom and disgust, of eternal visions over earthly ones, of life over death”.viii

Spaces women carve out for themselves within religious traditions may have a uniquely feminist bent. Meredith McGuire writes in “Embodied Practices: Negotiation and Resistance” that rituals reserved for women often “transform or sacralize aspects of women’s everyday lives that are disvalued or denigrated in the dominant religious practices”.ix Feminist ritual practices like the May Crowning, then, can be a way for Catholic women to work against their own religious traditions in the context of those traditions themselves, a concept often referred to in feminist theology as “defecting in place”.x

McGuire also argues that women’s spiritual practices are “likely to take bodily expression” and “link body and spirit”.xi It makes sense, then, that the May Crowning ritual should primarily be focused on externalities; perhaps the white dresses and flowers are simply a way for women to embody the religious rituals of Catholicism usually reserved for male priests.

Certain aspects of Mundelein May Crowning ceremonies reflect this counterculture. Celebrations of the May Crowning were often combined with a Mother’s Day prayer service, which grounded the ceremony in a celebration of the women important to Mundelein students in their daily lives.xii The students in graduation gowns, too, linked their devotion for the Virgin to their academic achievements, rather than their external appearance. These traditions speak to a broader potential framing of the May Crowning ceremony, that of a uniquely feminist ritual within the limitations of a larger religion.

A few weeks ago, I spent several days scanning and writing about hundreds of photographs from Mundelein College May Crowning ceremonies spanning decades. Year after year, girl after girl in white, but the statue remained the same, and so did the white marble steps of Piper Hall. I repeated the same process of scanning and describing each photo, and the process almost started to feel like a religious ritual in and of itself, an act of devotion not only to Mary but to the students celebrating her – and celebrating themselves. What did Mundelein students think of this ritual? The college’s relationship with feminism, as an institution dedicated to the formation of educated, independent women, albeit one with a strong relationship with many patriarchal aspects of the Catholic Church, is complex – as is the ideology of the May Crowning ceremony at large.

* Mundelein College, founded and operated by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM), provided education to women from 1930 until 1991, when it affiliated with Loyola University Chicago.

Anna is a Summer 2022 IHDI Assistant in the WLA. She recently graduated from Loyola University Chicago with a BA in political science and, after a year of service with AmeriCorps & the Jesuit Volunteer Corps Northwest, plans on pursuing graduate education in public history. She enjoys contemporary fiction, embroidery, and swimming in Lake Michigan. For more information about this post, contact wlarchives@luc.edu.

Figure 1. “May Crowning 1954”, May 5, 1954. Box 47, Folder 49, Mundelein College Photograph Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Figure 2. “May Crowning 1935”, May 1935. Box 47, Folder 41, Mundelein College Photograph Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Figure 3. “May Crowning 1944”, May 4, 1944. Box 47, Folder 45, Mundelein College Photograph Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Figure 4. “May Crowning 1962”, May 1962. Box 47, Folder 56, Mundelein College Photograph Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Chicago, IL.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed. Questions? Please contact the WLA at wlarchives@LUC.edu.