Warning: This blog post contains a reference to racial slurs targeted at black employees by Texaco executives, ca. 1993-1994.

In the fall of 1996, Texaco—one of the largest oil and natural gas companies in the United States—was rocked with scandal when audio tapes came to light that revealed top-level executives using offensive language in reference to their black employees. They also stood accused of conspiring to destroy documentation proving they participated in discriminatory employment practices. The “Texaco Tapes,” so-called in the press, became key evidence in the class action lawsuit Roberts vs. Texaco that was first launched against the corporation by minority employees in 1993. The recordings revealed company executives referring to their black employees as “black jelly beans” and “n****ers” while also discussing efforts to shred evidence the prosecution requested during the discovery phase of the investigation. [1] The company soon settled with the complainants for $176 million dollars; at that time, the highest settlement for a class action lawsuit in U.S history.

The story of the trial and its resolution are described in detail through the personal papers of lead plaintiff Bari-Ellen Roberts, who donated her materials documenting the case to the Women and Leadership Archives in 2003. Bari-Ellen Roberts graduated from Mundelein’s Weekend College in 1978.* This collection is unique for the breadth and depth of information highlighting the processes of a high-profile civil action lawsuit—not only does it contain Roberts’ copies of court documents, but the collection also holds copies of her personal journal during the years of the trial, national media coverage, and transcripts of the “Texaco Tapes” that effectively resolved the case. From Robert’s records, researchers can get a very real look into the process of the legal system in the United States as well as the personal turmoil that can result from a long battle in the court room. The Roberts vs. Texaco case is an important piece of history that shouldn’t be forgotten as important discussions related to the politics of race and gender continue to proliferate in America.

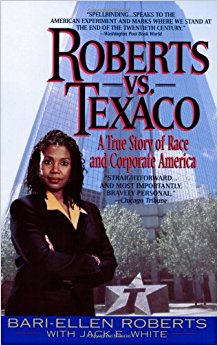

Roberts and her co-plaintiff Sil Chambers began the process of filing a class action lawsuit in 1993. Roberts joined Texaco after vacating a leadership position at Chase National Bank, where she became the first African American in the Corporate Trust Division to become Vice President. When the master trust she managed moved to another state Roberts sought out new job opportunities. She accepted a position with Texaco after a long negotiation that would foreshadow the rest of her time with the company—Roberts turned down two job offers before they offered her a salary commensurate with her previous experience. Texaco recruiters assured Roberts and other potential black applicants that the company was in the process of diversifying their leadership, telling Roberts they promoted candidates based on performance not color. In her memoir Roberts vs Texaco: A True Story of Race in Corporate America, Roberts remarks that she “kept [her] side of the bargain by working as hard and productively as any white man, but the reward Texaco promised… did not come.”[2]

At first Roberts, Chambers, and six other employees silently approached the ICCR (Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility) about their legal options, but it wasn’t until meeting with young lawyer Cyrus Mehri, then of the Washington, D.C law firm Cohen, Milstein, Hausfeld, and Toll, that legal intervention truly gained traction. In spite of the group’s resolve to move forward with the suit, Roberts felt conflicted about going through with it. Roberts wrote in her journal that she had a “real push pull kind of feeling.”[3] Should she jeopardize her financial stability to stand up to this monolithic company with seemingly limitless resources? Was it wise to embark on an expensive, not to mention emotionally taxing, process that could take years to reach an uncertain conclusion?

Her answer came shortly after she read over the final draft of the complaint. In January of 1994, Roberts applied for a managerial position being vacated by her supervisor. In her performance review given by the woman leaving the position, Roberts received a grade high enough to warrant the promotion. When senior management reviewed the evaluation, however, they countered that her performance did not warrant the grade and reduced it. They remarked that she was “uppity” and returned a lower grade that minimized Roberts’ chance of receiving the promotion.[4]

In February of 1994 a white male employee from another branch with less experience was placed in the position Roberts applied for. At the meeting announcing the change in staff, the head of Roberts’ department told her she could help train the new replacement—in front of her colleagues. This was an acknowledgement of everything Roberts knew about the treatment of minority employees at Texaco: they were competent enough to support executives but not good enough to actually be executives. Furious and humiliated, Roberts gave her lawyer the go-ahead to serve Texaco with the complaint. “No pulling back. We are going to call Cyrus and start pushing for the filing of this suit asap.”[1] The surrendered tapes as well as the report of an investigation into Texaco’s discriminatory practices by the EEOC (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) sealed the company’s fate.

As mentioned, the Women and Leadership Archives hold the records of Bari-Ellen Roberts, including the various court documents chronicling the events of the trial such as the transcripts of her personal journal, the infamous Texaco tapes, depositions taken by the defense team of the Texaco executives, and records of Roberts’ life after the trial. By reading the Bari-Ellen Roberts papers, researchers can get a full and detailed picture of the legal process at work in the United States, particularly civil action suits. As a result of my close study of the Roberts’ papers for this blog post, I now hold a fierce appreciation for the leadership she displayed in forging paths for black and other minority women in corporate America. Twenty years later, it is unfortunate that the records documenting her courageous efforts also reveal how far we have yet to go.

Click here to read an excerpt from a transcript of Roberts’ journal, February 1994.

*Mundelein College, founded and operated by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM), provided education to women from 1930 until 1991, when it affiliated with Loyola University Chicago.

[1] “Roberts’ Journal of Racial Discrimination Case,” Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago, Bari-Ellen Roberts Papers, Box 1, Folder 4.

[2] Bari-Ellen Roberts, Roberts Vs. Texaco: A True Story of Race and Corporate America (New York: Avon Books, 1998), 1-2.

[3] “Roberts’ Journal of the Discrimination Case,” Woman and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

[4] ibid.

[5] ibid.

Ellen is a Graduate Assistant at the WLA and is in the second year of her M.A in Public History at Loyola University Chicago. Before moving to Chicago, Ellen was a Kindergarten teacher in Louisiana. She enjoys brunch, procedural dramas, and pugs.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.