This summer, the Loyola Libraries are excited to bring you the World Cup of Books, an interactive program to encourage reading books from other countries. Show your support for your favorite team by reading books from and about their country!

Today’s match-ups include England v Belgium, Panama v Tunisia, Japan v Poland, and Senegal v Colombia.

England: Life after life by Kate Atkinson

If you could travel back in time and kill Hitler, would you? Of course you would.

Atkinson’s (Started Early, Took My Dog, 2011, etc.) latest opens with that conceit, a hoary what-if of college dorm discussions and, for that matter, of other published yarns (including one, mutatis mutandis, by no less an eminence than George Steiner). But Atkinson isn’t being lazy, not in the least: Her protagonist’s encounter with der Führer is just one of several possible futures. Call it a more learned version of Groundhog Day, but that character can die at birth, or she can flourish and blossom; she can be wealthy, or she can be a fugitive; she can be the victim of rape, or she can choose her sexual destiny. All these possibilities arise, and all take the story in different directions, as if to say: We scarcely know ourselves, so what do we know of the lives of those who came before us, including our own parents and—in this instance—our unconventional grandmother? And all these possibilities sometimes entwine, near to the point of confusion.—Kirkus Review

Find it here, or on display at Lewis!

Belgium: My little war by Louis Paul Boon, translated by Paul Vincent

In this peculiar WWII novel, first published in 1947, the Flemish author gives his own first name, Louis, to the narrator, but also insists that the “I” of his first-person narration is also “you,” the reader. As someone whose generation “blossomed between the two wars,” Louis offers a heavy dose of overtly symbolic disillusionment and self-conscious sentimentality while writing very little about the war itself. Mostly, he’s at home contemplating the people in his neighborhood. An “anarchist, nihilist, and a dirty old man,” Louis can’t quite identify anything connected with the war, and this ambiguity is of course meant to question the nature of war itself. Instead, the reader gets lost in a strange, vague world where multiple characters are referred to as “What’s-his-name” and musings on misery are italicized or printed in capital letters. This cursory treatment of reality allows Boon more time to talk about himself, the decline of humanity (best illustrated by loose women), and the feigned hypersensitivity that accompanies all great nihilist authors, but that Boon can’t quite get right.—Publishers Weekly

Find it here!

Panama: When new flowers bloomed: short stories by women writers from Costa Rica and Panama by Enrique Jaramillo Levi 1944- 1991

Women writers from the Central American nations of Costa Rica and Panama have distinguished themselves in the fields of short fiction and poetry during recent years. Their triumph mirrors their countries’ struggles to overcome poverty and political violence. The quality and sheer number of their stories testify to their ongoing pursuit of artistic perfection. The women whose stories have been especially translated into English for this special issue have found the key to effective communication by searching their hearts and minds, and by exploring the intricately textured web of life that surrounds them. Costa Rica and Panama are linked by culture, geographical location and political history. A recent earthquake that struck sections of both countries at once underlined their similar vulnerability to natural disaster. A deep and continuous theme running through these writings is a note of hope for a calmer future.–Goodreads

Find it here!

Tunisia: Wounding words: a woman’s journal in Tunisia by Evelyn Accad, translated by Cynthia T. Hahn

At heart, this is a work of intelligent nonfiction, which Accad, a Lebanese feminist scholar and novelist has unfortunately tried to cast in a fictional guise. At the center of this earnest, occasionally intriguing fictionalized autobiography is Hayate, a feminist scholar from Beirut who visits Tunisia to acquaint herself with the women’s movement in “”the most democratic”” country in the Arab world–where civil rights were updated in 1956 to include women as almost equal participants. However, as Hayate quickly learns, traditional Islamic culture and custom overrides many civic laws; Tunisia is still “”a country where women are considered permanently under age.”” The narrative consists largely of Hayate’s attendance at various women’s meetings, where the topics include their deeply conflicted sexuality; devastating accounts of abusive husbands; activists’ tales of arrest, imprisonment, and even torture for protesting sexist legislation; and energetic if somewhat simplistic arguments about Marxism and pacifism. Along the way, Hayate must give up her peaceful rented house on the Mediterranean when the landlord accosts her; forges several close friendships; and finds herself the victim of misdirected anti-American sentiment from some feminists. Though readers comes away with quite a vivid portrait of life for women in contemporary, urban Tunisia, they are subject to a poorly crafted, rambling narrative that is littered with well-meaning but uninspired poetry.—Publishers Weekly

Find it here!

Japan: Me by Tomoyuki Hoshino, translated by Charles De Wolf

Hoshino (The Mermaid Sings Wake Up) draws inspiration from the “It’s me” telephone scams that prey mostly on Japan’s elderly, opening with mischievous Hitoshi Nagano as he takes the cell phone of Daiki Hiyama and (posing as Daiki) asks the young man’s mother for ¥900,000. Hitoshi explains that the wire is to pay a debt to a friend, and then gives her his actual name and bank account. Three days later, Daiki’s mother appears in Hitoshi’s home and, calling him Daiki, treats Hitoshi as if he is her son. From this point, the ordinary life of the characters transforms, as Hoshino leads readers on a psychological and philosophical journey in which the value of individualism is questioned and tested in escalating absurdist measures. When Hitoshi visits his old home, he finds another young man living as his parents’ son and is treated as an imposter by his mother. The novel is most successful during Hoshino’s riffs on parents obsessed with making sure their children achieve respectable vocations and marriages, value children more for their lack of individualism than for their unique talents and eventually losing sight of their adult children’s identities. In Hoshino’s dystopia, identities are fluid and any one is as good as another. The novel pushes this idea into a highly plotted, absurd world where normally shocking movements are rendered as reportage, depicted with the same emotional weight as casual conversations. Hoshino’s ambitious novel is pleasingly uncomfortable.—Publishers Weekly

Find it here, or at the IC display!

Poland: Our Life Grows (uncensored) by Ryszard Krynicki, translated by Alissa Valles

The first uncensored, English-language translation of a Polish dissident poet’s brave act of witness in post-World-War-II Europe. The Polish poet Ryszard Krynicki, born in a Nazi labor camp in Austria in 1943, became one of the most prominent poets of the New Wave generation of 1968, his poetry offering what Adam Michnik has called “a strange and beautiful testimony,” merging “Conrad’s heroic ethics with a great metaphysical perspective.” Krynicki is the author of a body of work marked at once by the solitude of a poète maudit and solidarity with a hurt and manipulated community. The collection Our Life Grows appeared first in an edition crippled by communist censorship, then in 1978, in the uncensored Paris edition that forms the basis for this translation. These poems, combining a biting wit and rigorously questioning mind with a surreal imagination, are a vital part of the story of postwar Europe. –National Library Board

Find it here, or on display at Lewis!

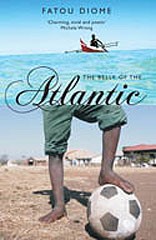

Senegal: The Belly of the Atlantic by Fatou Diome (Author), Ros Schwartz (Translator), Lulu Norman (Translator)

The third-world native must leave home if he is not only to succeed but also triumph. If he does so, he can never be at home again. Salie, the Senegalese native, who narrates The Belly of the Atlantic, says on a visit to Niodior, the Senegalese island where she was born, that, “I go home as a tourist in my own country, for I have become the other for the people I continue to call my family.” When she checks into a hotel on the mainland, the clerk thinks she is a prostitute and asks when her client will arrive to pay for the room. No Senegalese woman can afford a room of her own.—Words without Borders

Find it here, or on display at the IC.

Colombia: The sound of things falling by Juan Gabriel Vásquez

An odd coincidence leads Antonio Yammara, a law professor and narrator of this novel from Latin American author Vásquez (The Informers, 2009, etc.), deep into the mystery of personality, both his own and especially that of Ricardo Laverde, a casual acquaintance of Yammara before he was gunned down on the streets of Bogotá.

The catalyst for memory here is perhaps unique in the history of the novel, for Yammara begins by recounting an anecdote involving a hippopotamus that had escaped from a zoo established in Colombia’s Magdalena Valley by the drug baron Pablo Escobar. After the hippo is shot, Yammara is taken back 13 years to his acquaintance with Laverde, a pilot involved in drug running. Yammara is a youngish professor of law in Bogotá, and, generally bored, he spends his nights bedding his students and playing billiards. Engaged in the latter activity, Yammara meets Laverde without knowing his background—for example, that Laverde had just been released from a 19-year prison stint for drug activity. A short time later, Yammara is with Laverde when the drug runner is murdered, and Yammara is also hit by a bullet. He is both angered and intrigued by Laverde’s murder and wants to find out the mystery behind his life. His curiosity leads him circuitously to Laverde’s relationship with Elena, his American wife, whose death in a plane accident Laverde was grieving over at the time of his murder. Yammara meets Maya Fritts, Laverde’s daughter by Elena, who fills in some of the gaps in Yammara’s knowledge, and the intimacy that arises from Yammara’s growing knowledge of Laverde’s family leads him and Maya to briefly become lovers.—Kirkus Reviews

Find it here!