At the end of the 1960s, Mundelein College* was in the midst of a cultural crisis. A changing social landscape accompanied by financial and enrollment struggles pushed the college to reevaluate their educational point of view. Historian Tim Lacy writes, “Catholic women’s colleges in the United States juggled a series of sometimes competing, sometimes complementary interests. Faculty and students juxtaposed their Catholic identity, the progress of feminism in American culture, pedagogical innovation, and the increasing presence of laity in administration.”1 Mundelein was far from the only Catholic women’s college to experience a cultural shift at the time, but the school’s reaction to this tension was particularly unique.

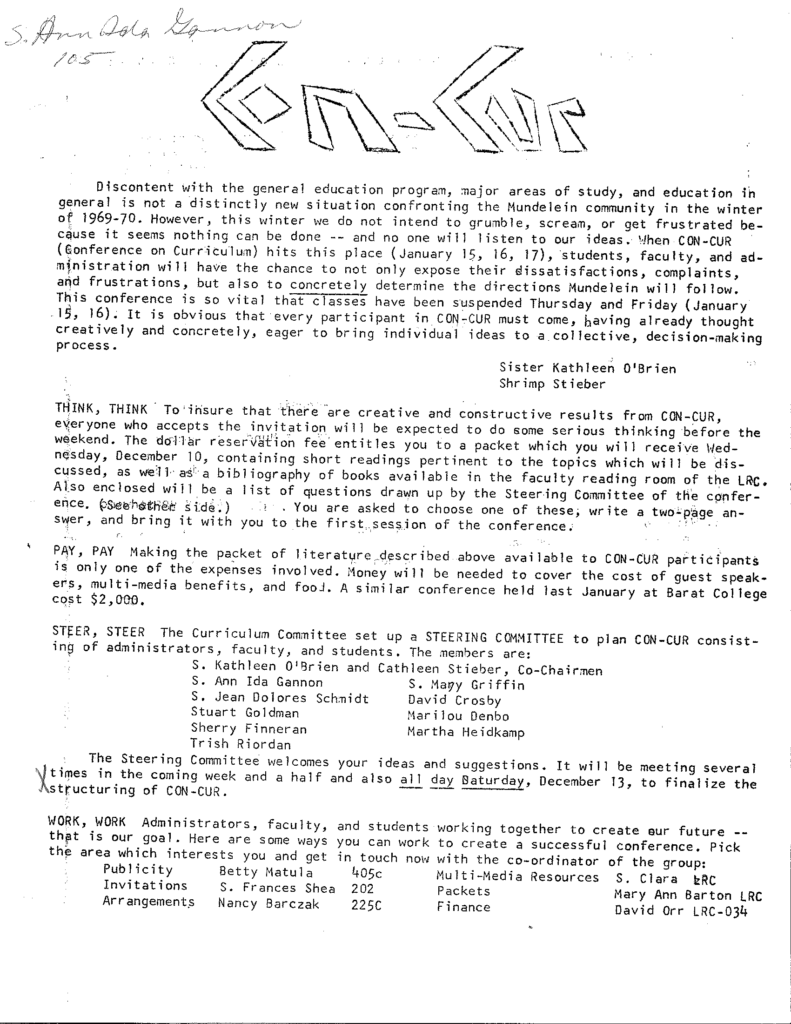

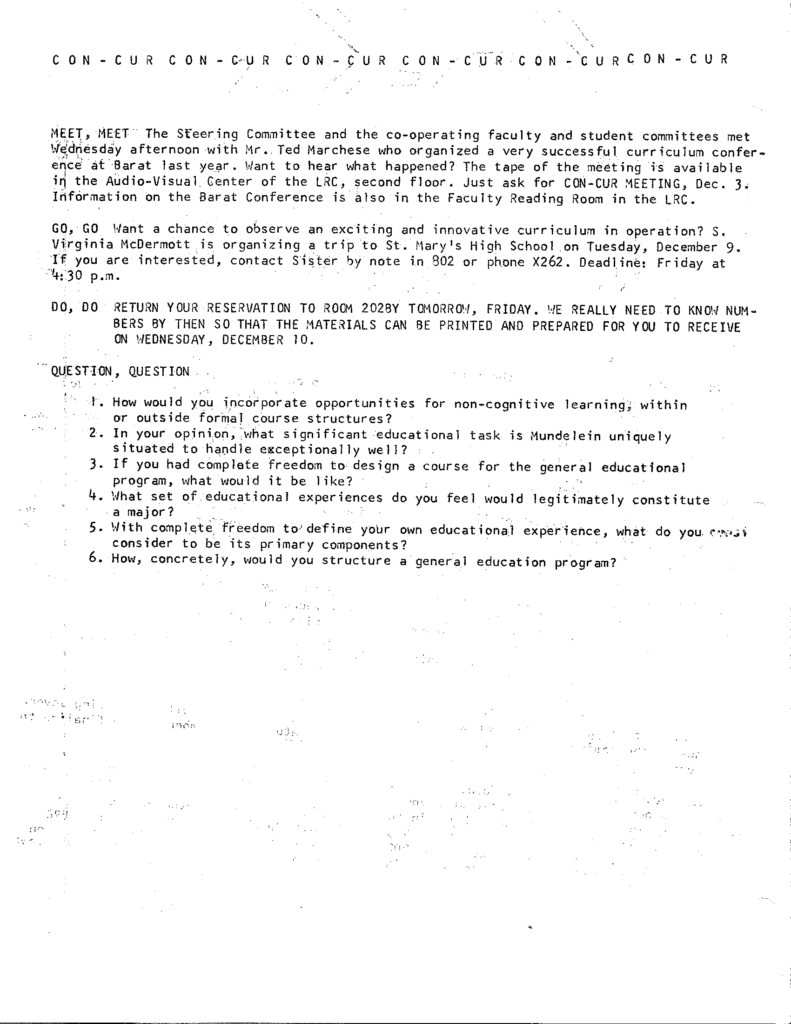

In the fall of 1969, the Curriculum Committee of Mundelein College’s Faculty Senate arranged a three-day Conference on Curriculum, known as Con-Cur, for the following January. The conference was designed specifically to receive and respond to the needs of the Mundelein community. The invitation for the event strongly emphasized that this was a conference for students, faculty, and administration to share their ideas for the future of Mundelein College. Classes were suspended at Mundelein on January 15th and 16th, the first two days of the conference, to encourage student participation.

The invitation for Con-Cur gives a clear idea as to what the organizers had in mind for this conference. Questions listed at the end of the invite ask, “How would you incorporate opportunities for non-cognitive learning, within or outside formal course structures?” and “How, concretely, would you structure a general education program?” Mundelein College was looking to adapt, and the school needed the input of its students to successfully evolve.

Another piece of information from the Con-Cur invite provides a glimpse into the inspiration for Mundelein’s future experimental education programs. The invitation promotes an outing in December of 1969 led by Virginia Anne McDermott, BVM to St. Mary High School to “observe an exciting and innovative curriculum in operation.” St. Mary was an all-girls Catholic academy in Chicago, founded by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 1899. In 1968, the school restructured as the St. Mary Center for Learning, “an interracial, nondenominational model in alternative education,” according to the St. Mary Alumnae Association.2 The Center focused on community decision making, experiential learning, and student organized classes, concepts that would feature prominently in Mundelein’s answers to their education questions.

As a conference, Con-Cur was organized by breaking into task forces that corresponded with the goals of the event, like the General Education Task Force and the Black Studies Program Proposal Task Force. The Task Force for Experimental Education was the group that suggested the initiation of an Experimental College in the fall of 1970, a program that would come to be known as Mandala.

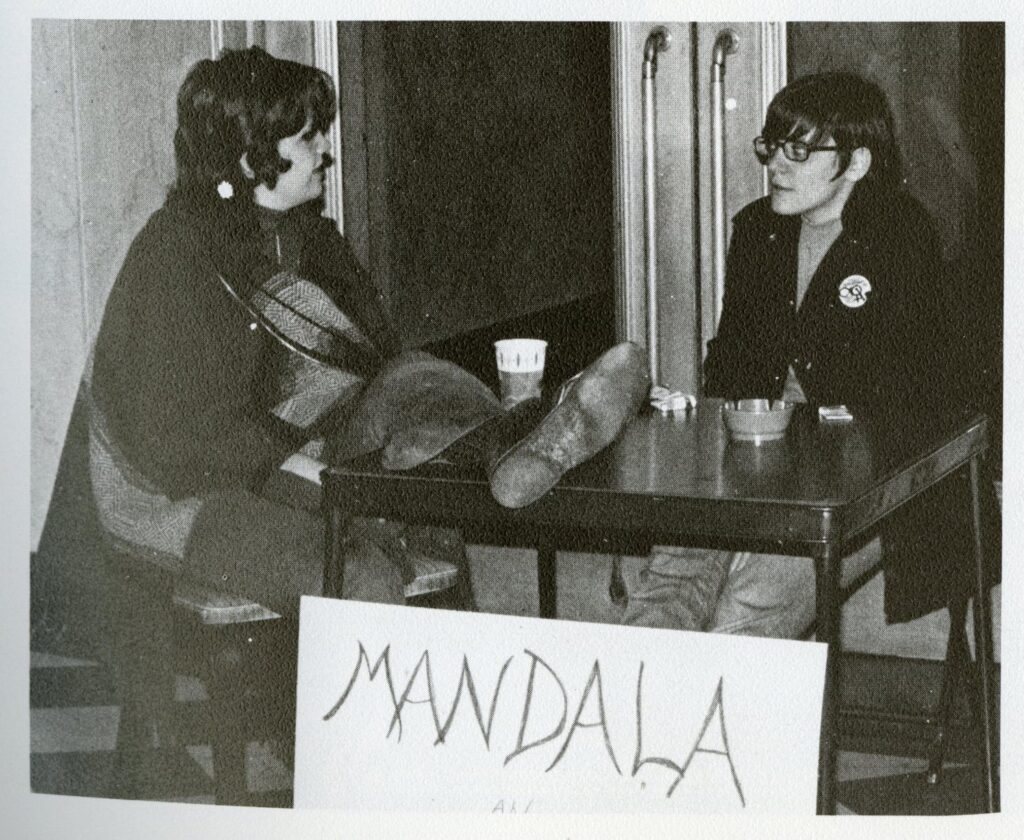

Mandala, in operation from 1970 to about 1973, was a curriculum based on deconstructing traditional educational structures. The program was launched with four Mundelein faculty members: David Crosby, director of Mandala; William Hill, Gerry Honigsblum, and David Orr (who, later in his life, served as the mayor of Chicago for 7 days). Crosby described the program as composed of “two innovations which distinguish it from the regular program: 1) elimination of the credit system; 2) joint student-faculty responsibility for all phases of academic programs.”3 At the beginning of the program, students wrote a contract in which they outlined their educational goals and a program of study designed to reach said goals. The plans of study were often a combination of job experience, travel, and formal coursework that combined to create a comprehensive educational experience. When the terms of the contract were sufficiently met, Mandala decided as a group to recommend the student to the Academic Dean for a degree.

As an experimental program, Mandala inherently had challenges to overcome. The entirety of the Mandala program, including students and faculty, met weekly to discuss their progress in their respective studies and the overall operations of the program. These meetings were a key element of the collaborative structure of Mandala but were also where the struggles of running a pilot program rose to the surface. “Some of the frustration undoubtedly derives from the special problems of our first year,” Crosby wrote in an interim program report in 1971. “We have had to create all our own procedures from scratch, and often have been reluctant to commit ourselves as a group to any specific procedures without first exhausting ourselves in seemingly endless deliberations. The mechanisms for decision-making had to be evolved rather slowly, then re-examined and evolved again.”4

For those students who participated, Mandala was overall a positive and enriching chapter in their educational journey. Early in 1973, Susan Reynolds wrote a story about the success of Mandala for Dialogue, a Mundelein College student newspaper. Reynolds reported that the majority of Mandala students interviewed “stated they felt the uniqueness of their Mandala experience had helped rather than hindered them.” Despite the positive outlook of the article, Mandala was already on the way out by 1973.

A unique challenge posed by the curricular structure of the program was the problem of tuition. In the first year of Mandala, a student was interested in taking classes at Columbia College to contribute to their educational contract. They requested a tuition refund from Mundelein to offset the cost of the courses at Columbia. In the fall of 1971, a Mandala student planned to travel to Europe in order to fulfil their program contract. They requested to not pay tuition for the duration of the fall semester, given they would not have access to Mundelein College resources and facilities overseas. These conflicts illuminate the struggles of balancing educational creativity and responsibility. In response to these questions of finances, Crosby writes, “I realize that in a time of financial restrictions it is difficult to adopt policies involving a reduction in tuition income, but I believe Mandala students are, in these particular respects, not currently on equal footing with students in the regular program.5” Mandala wanted to create something new but had to function within the bounds of Mundelein College and higher education to do so.

The second problem that loomed over Mandala was enrollment. Correspondence between David Crosby and academic dean Robert LaDu documents a growing concern over the shrinking size of the program, and a frustration with a seeming inability to appeal to the Mundelein community.6 In December of 1970, faculty projected Mandala enrollment of 45 for the following academic year. During Winter term of 1971, total enrollment was 11. Mandala contributed some of their low enrollment numbers to an inability to appeal to the Mundelein community. In a letter to LaDu, Crosby writes, “The most distressing aspect of Mandala’s situation is its ability to appeal to students, faculty, and administrators outside the Mundelein community while making little or no headway within Mundelein.” The program was receiving inquiries from across the country but had trouble getting a foothold in their own college.

By 1972, the administration had accepted the fate of the program. In the fall of that year, Mandala stopped accepting new students, with enrollment numbers dropping down to single digits. Reflecting on the project in 1973, LaDu wrote, “While I have a great deal of regret at seeing Mandala disappear—for besides the many tangible benefits it gave to the College, it also provided no less valuable intangible ones such as helping to identify the limits of our institutional creativity and commitment to alternate ways of learning.” Mandala was not the first experiment in education at Mundelein College, but it was the last before Mundelein’s home run in alternative education: Weekend College.

During a faculty meeting in the summer of 1974, Mary Griffin, BVM started an ad hoc committee to plan a possible weekend college project. The committee was made up of Griffin, Mary De Cock, BVM, Daniel Vallaincourt, and two members of the Mandala faculty, Bill Hill and David Orr. In the document that outlines the philosophy of Weekend College (WEC), Griffin describes the changing landscape of education, and how the reassessment of higher education at Mundelein created a “serendipitous by-product…an upsurge of creative thinking by college faculty and administrators and an increase in experimentation with new educational models,” through which both Mandala and Weekend College were born. WEC was structured as a program for full-time workers, where students would stay in residence at Mundelein College from Friday to Sunday one out of every three weekends, designed to serve those who were unable to commit to classes on weeknights or every weekend.

The pilot program was launched June 11, 1974. In 70 days, the college received over 1000 requests for information and 87 applications. The explosion of interest in the program indicated to the college that they had finally found their niche: serving the needs of working adults. The Weekend College would grow to comprise over half of Mundelein College’s enrollment and became one of the most lasting legacies of the school. Similar programs were established throughout the country.

The achievements of WEC were a direct result of Con-Cur in 1970, when a community of students and educators came together to dream up something new. Mundelein College was willing to take risks and try something different, and when it didn’t work the first time, they tried again. The beauty of higher education is providing a space for people to make mistakes and learn from them, and the failures of Mandala made way for the successes of Weekend College.

Learn more through the Mundelein College Digital Collections

* Mundelein College, founded and operated by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM), provided education to women from 1930 until 1991, when it affiliated with Loyola University Chicago.

Kaylee is in their second year of master’s programs in Public History and Library and Information Sciences. They have a BA in History, with interests in art history and religious studies. They love calico cats, crocheting, and going to museums in their free time. For more information about this post, contact wlarchives@luc.edu.

Footnotes

1 Lacy, Tim. “Understanding ‘Strategies for Learning:’ Pedagogy, Feminism, and Academic Culture at Mundelein College, 1957-1991.” American Catholic Studies 116, no. 2 (2005): 39–66.

2 St Mary High School Centennial Celebration Brochure, 26 September 1998, box 11, folder 2, St. Mary’s, Ann Ida Gannon, BVM Papers, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago.

3 Women and Leadership Archives. Loyola University Chicago. Mundelein College Paper Records, Mandala Interim Report, 1971. Box 286, Folder 9.

4 Mandala Interim Report, 1971.

5 Women and Leadership Archives. Loyola University Chicago. Mundelein College Paper Records, Letter from David Crosby to Sister Ann Ida Gannon and Robert LaDu, 27 January 1972. Box 286, Folder 9.

6 Women and Leadership Archives. Loyola University Chicago. Mundelein College Paper Records. Box 286, Folder 9.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Questions? Please contact the WLA at wlarchives@LUC.edu.