The Women and Leadership Archives hold the papers of Sheli Lulkin, a long-time organizer in Chicago’s northern neighborhoods. Lulkin moved to the Edgewater neighborhood in the late 1970s to pursue a doctorate in political science from Loyola University Chicago. She completed her coursework, but before finishing her dissertation she began community engagement within her condominium and around pressing issues in Edgewater. The first issue that she dedicated major time and effort to was the potential sale of land in Rosehill Cemetery.

In the Ravenswood neighborhood of Chicago is historic Rosehill Cemetery, located about a mile and a half southwest of Loyola. Rosehill was first established in 1859 as Chicago officials moved burials outside of city limits. Initial formal cemeteries in Chicago, established in the 1830s, were within city limits, but concerns with health and sanitation worsened by flooding and improper drainage ended municipal burials by the end of the Civil War. Bodies buried in modern-day Lincoln Park were moved to Rosehill Cemetery in the then-village of Lakeview. Chicago’s northern border grew over time to encapsulate the land, and today Rosehill is the largest cemetery in the city. It is also one of the oldest cemeteries in the city; early burial records no longer exist as they were stored in a Loop office and destroyed during the Great Chicago Fire. Those who did have to reinter their loved ones in Rosehill in the 1860s were anxious about further disturbances. These worries were soothed by the language of the cemetery’s charter, which asserted that the land was dedicated exclusively for burials in perpetuity.

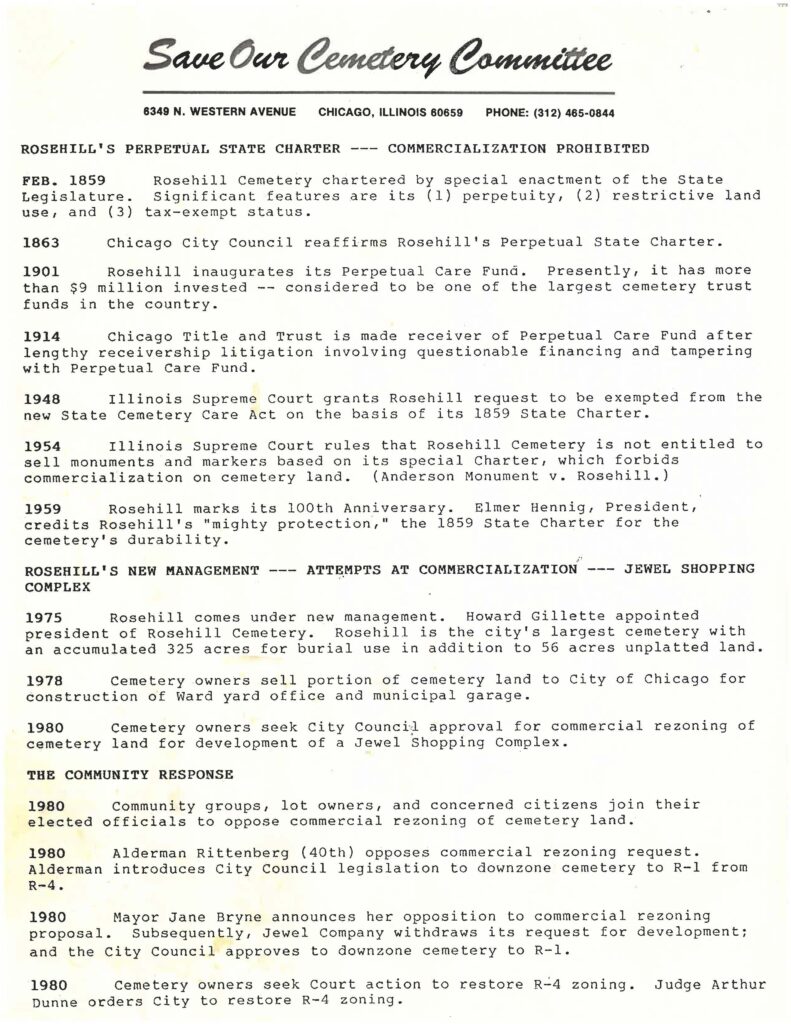

In 1859, the Illinois state legislature approved the charter to incorporate the Rosehill Cemetery Company. The charter was restrictive by design and limited the company to use its assets solely for the establishment and maintenance of a rural cemetery. The Rosehill company regularly used this legal feature as a selling point for potential clients. In promotional material for the Rosehill Mausoleum, constructed in 1913, the first listed advantage of the cemetery is “the mighty and yet invisible protection which will enfold it and its precious contents for all time…This charter gave the entire cemetery absolute immunity from any forced change. Forever, no thoroughfare can be opened through the grounds; no portion of the cemetery can ever be condemned.”1 Given this guarantee, the surrounding community was disturbed by the continuous threats of development posed to Rosehill during the 1980s.

In 1980, the grocery chain Jewel was interested in paying $9 million for 15 acres on the western edge of Rosehill Cemetery to develop a shopping center featuring a grocery store, drugstore, a laundromat, and other specialty stores, contingent on Jewel’s ability to convince the city to rezone the property. By August of that year, Jewel rescinded their project proposal after Mayor Jane Byrne voiced support for anti-development community members. The serious backlash against the commercialization of Rosehill Cemetery was key in its conservation. Community organizations like Neighbors of Arcadia Terrace, Association of Sheridan Condo-Co-op Owners, and Bryn Mawr Neighbors Association were vocally opposed to development, and Jewel became quickly uninterested in the project. Soon after the grocery chain exited, these neighborhood collectives would unite again over cemetery preservation.

In 1983, Chicago heir and investor Potter Palmer IV purchased the assets of the Rosehill Cemetery Company for approximately $2.36 million and incorporated his own company, Rosehill Memorial Inc. to take over operations, thus avoiding the restrictions of the original charter. The name Potter Palmer was likely familiar to many of the Chicagoans first buried in Rosehill. The new owner’s great-grandfather, Potter Palmer Sr., sold his dry goods business in 1867—the eventual Marshall Field & Company—to enter the world of real estate. He widened State Street and established it as the main downtown commercial district, including the construction of the Palmer House—a luxury hotel first built in 1870 as a wedding present for his wife, Bertha Honoré Palmer. Prior to entering the funerary business, Potter Palmer IV was an investor and partial owner of the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves and the Harlem Globetrotters. Rosehill was Palmer’s first company he owned outright. He was quoted in the Sun-Times on April 3, 1984 as “looking for a company in the Chicago area that would be easy to keep track of and to get involved with on a day-to-day basis.”2

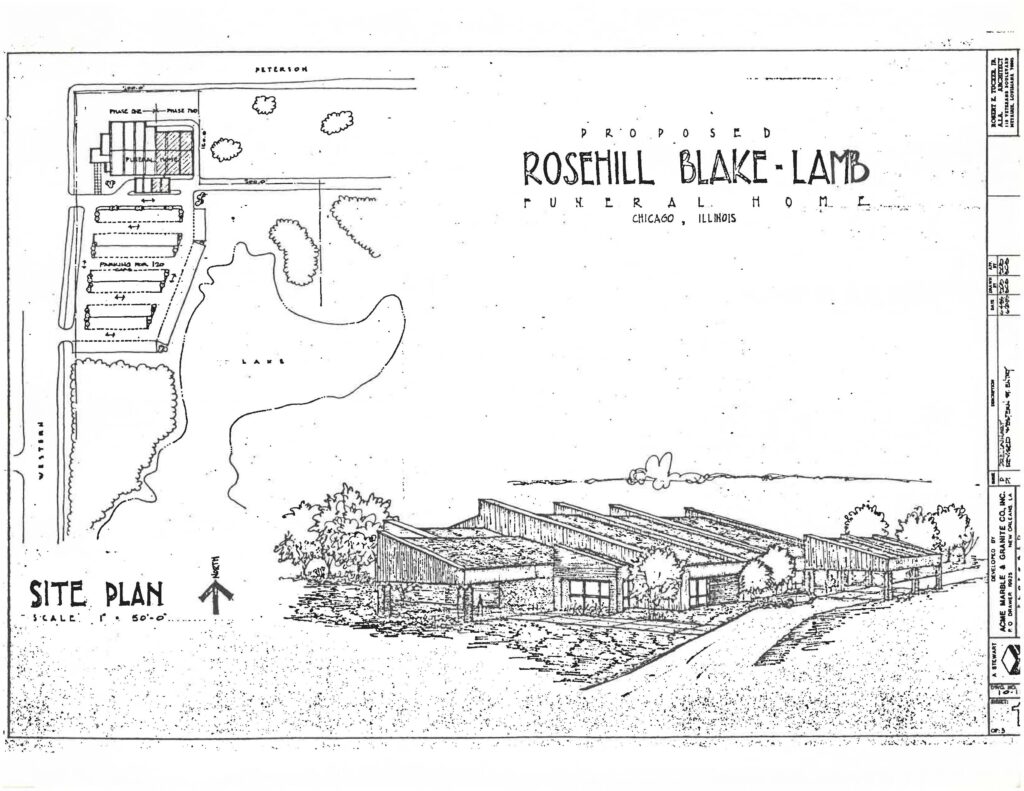

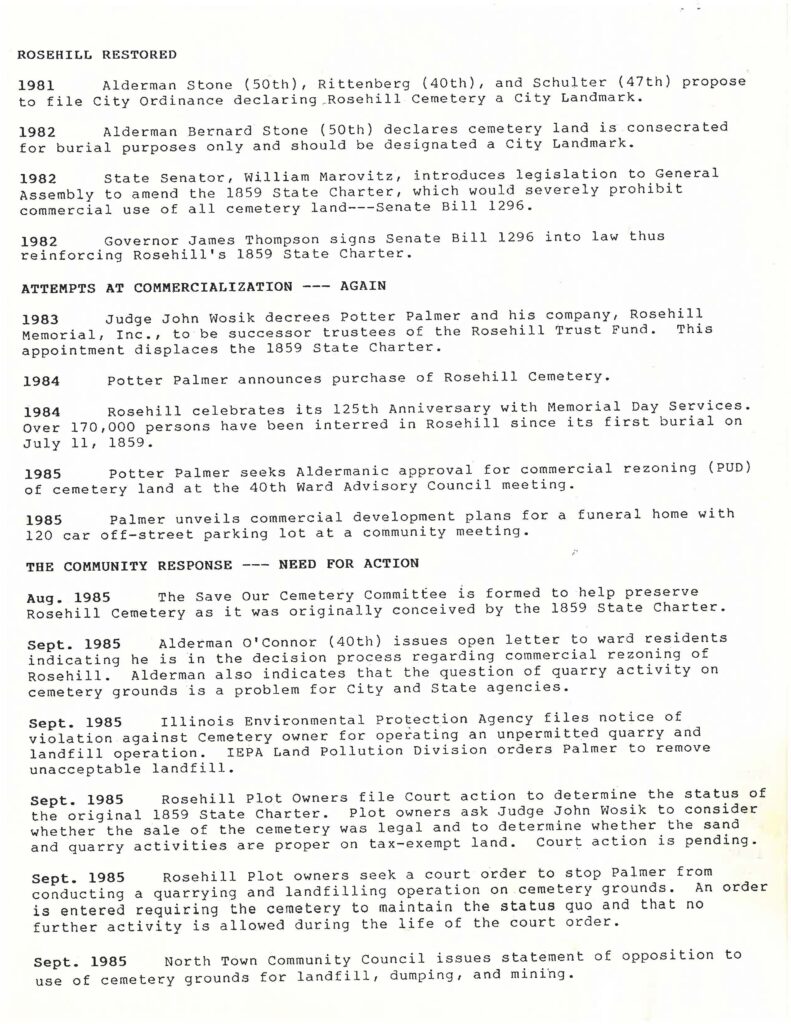

In a community meeting on July 19, 1985, Potter Palmer and his legal representatives floated the idea of constructing a funeral home and parking lot on unplatted cemetery land. Residents were concerned by the attorney Daniel Houlihan’s assertion that the 1859 charter preventing commercial use had been dissolved, and attendees doubted Palmer’s pledge of no further development after the funeral home. In response to these proposed developments, community members like Sheli Lulkin assembled the Save Our Cemetery Committee (SOCC) in August of 1985 to organize and fight against cemetery construction. In the committee’s investigations toward legal action, SOCC discovered Palmer was quarrying sand and operating a landfill inside the cemetery. The new Rosehill Company was simultaneously planning a construction project and extracting resources from cemetery grounds, both projects with considerable environmental impact. At this point, SOCC realized they would need money and influence to take effective legal action.

On behalf of the committee, Sheli Lulkin sent a letter to Chicago investor and perennial Forbes 400 feature Henry Crown asking for assistance, appealing to the Crown family because of their own plots in Rosehill. Lulkin asked directly, “the purpose of this letter is to request your aid and support.”3 Henry Crown’s son, fellow Chicago investor and perennial Forbes 400 feature Lester Crown signed onto the lawsuit and was a vocal opponent of Palmer’s management of the property. With proper legal representation and financial support, the Save Our Cemetery Committee entered a years-long process of lawsuits and appeals concerning whether the 1859 Rosehill charter applied to Palmer’s new corporation.

In 1988, Palmer’s promises of no further development fell flat, as news broke that Rosehill was in negotiations with the Waldorf School and Open Lands Project to sell land parcels, the former to build a new facility and the latter to create park space. This announcement was more evidence for the Save Our Cemetery Committee of the risk posed to the exclusive status of Rosehill as a cemetery. Continued litigation, however, was not feasible for SOCC even with the support of high-profile Chicagoans like the Crowns. They and Palmer settled out of court in 1986, Palmer appealed in 1987, and the settlement was renegotiated in 1990. Though legally the conflict was over, not all were satisfied. Jim Chronis, a chairman of the Save Our Cemetery Committee, stated that he did not believe the question of the original charter was answered, but “it would be impractical for a community-based organization to carry out a legal challenge to Palmer’s plan.”4

Palmer’s plans for Rosehill would never come to fruition, as he sold Rosehill to Texas-based funeral and cemetery company Service Corporation International in 1991. The funeral home and parking lot were never constructed, and the Waldorf School never purchased a lot. Only one non-burial project has been completed, when the Chicago Park District dedicated the West Ridge Nature Park on unplatted Rosehill land in 2015.

Lulkin’s involvement in the Save Our Cemetery Committee prepared her for further community organizing. She served as president of the Association of Sheridan Condominium/Co-op Owners for 32 years and the Executive Director of the Edgewater Chamber of Commerce for 19 years. The physical paper trail of a local figure like Sheli provides a framework through which to study and learn from the tactics used by neighborhood organizations to negotiate the makeup of a community. When made available in archival settings, the strategies of neighborhood associations are available for future investigation and analysis. In the case of Rosehill Cemetery and the Save Our Cemetery Committee, the most effective strategy for implementing change was making noise. The public outcry around potential land development is what prevented it from moving forward, a tactic that can be replicated by contemporary organizers. The members of SOCC were determined to have a say in the shape of their community, and their work can be used as a launching pad for future organizers looking to create change in a similar fashion.

Kaylee is in their second year of master’s programs in Public History and Library and Information Sciences. They have a BA in History, with interests in art history and religious studies. They love calico cats, crocheting, and going to museums in their free time. For more information about this post, contact wlarchives@luc.edu.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Questions? Please contact the WLA at wlarchives@LUC.edu.