Every archive has areas it collects in, known as a collecting focus or collection policy. At the Women and Leadership Archives, one area of collecting focus is women artists’ papers, with special interest in Chicago and Midwest-based artists (see our full collection policy here). One might wonder why such a policy exists – after all, aren’t archives supposed to take everything historical?

Not quite. Having a collecting focus is useful for several reasons. First, it allows archives to focus their resources instead of stretching themselves too thin. Space and time are finite after all! Secondly, it facilitates the research process, since researchers can find related collections at a single place, instead of having to expend time and effort at different institutions. Lastly, it also allows collections within a single institution to speak to one another.

Taking women artists’ papers at the WLA as an example to illustrate the last point, we could ask the following. How did different artists engage in public art initiatives? How were women’s issues explored in their work? What kinds of issues? To show that these questions are not merely rhetorical, this blog post will look at a WLA digital collection, “Visions: A Highlight of Chicago Women Artists” (henceforth known as “Visions”), to trace the connections between different collections.

Overview of Visions: A Highlight of Chicago Women Artists

Through documents such as artwork, exhibition catalogs, correspondence, artists’ statements and press coverage, “Visions” gives a glimpse into the careers of ten Chicago-based artists and artist groups. The artists worked with media ranging from photographs to non-recycled plastic waste and addressed themes spanning the gamut of perceptions of the body to interrogations of the structure and psychological implications present in the work of Italian pre-Renaissance artists.

Given the rich range of interests and media reflected in the collection, how does one begin to make sense of it?

In the sections that follow, I will be exploring some ways in which the artists can be placed in conversation with one another. I will also look at how the collection can give insights beyond the artists’ individual careers and into the Chicago arts scene. Linked artists’ names lead to finding aids of their papers at the Women and Leadership Archives.

Women’s experiences

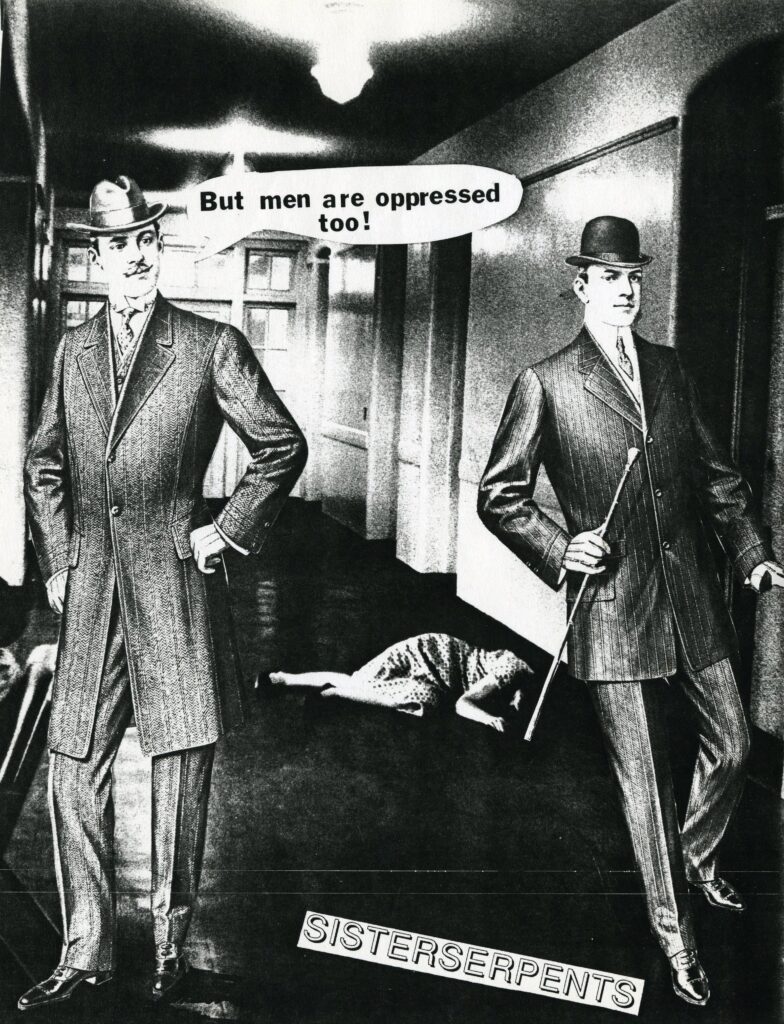

The SisterSerpents, Lindsay Obermeyer, and Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman sought to raise awareness of the issues that women faced. Established on July 4, 1989, SisterSerpents was a Chicago-based women artist group whose members were feminist artist-activists seeking to use their art to raise awareness on issues that women faced (read their manifesto here). Participation in the collective was largely anonymous. However, some members such as Mary Ellen Croteau (also featured in the digital collection) exhibited both their independent works and collective pieces they created.

Adopting installations and guerilla-style tactics such as putting up provocative street posters and stickers all over Chicago, the SisterSerpents highlighted issues confronting women such as misogyny, motherhood and subversive messages in the media. One of their installations, “Dart Game”, invited participants to take part in a dart game where the targets were “misogynists, pillars of patriarchy and obnoxious role models”. To read more about the SisterSerpents’ work and the reception they received, check out this blog post here.

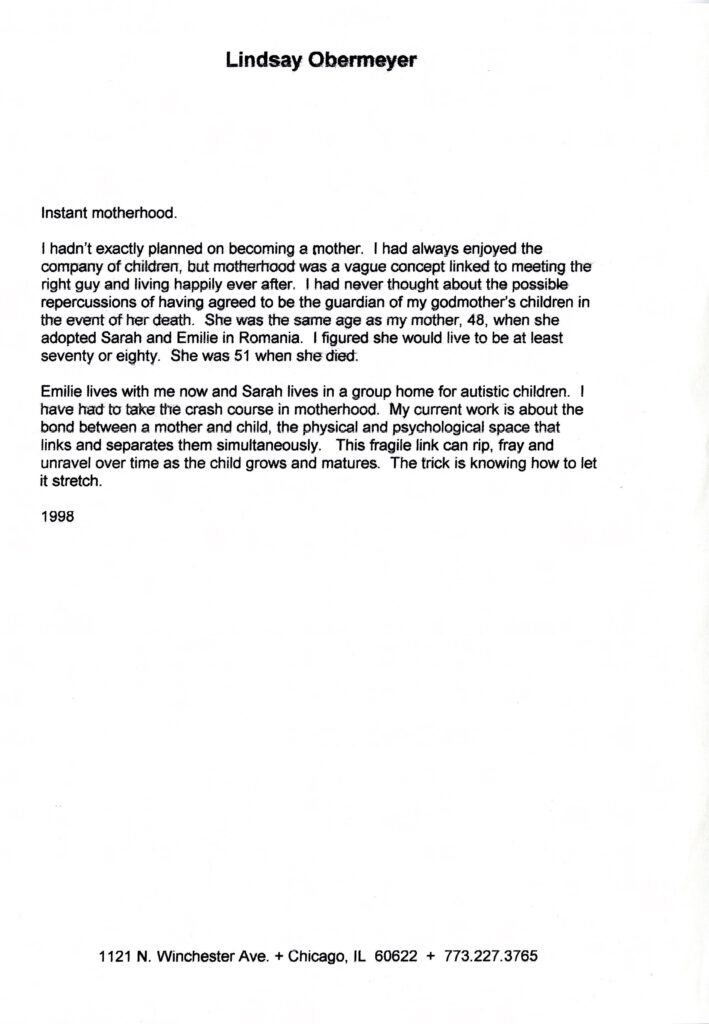

Lindsay Obermeyer’s work chiefly lies in fiber arts, beadwork and historical fashion. Influenced by her battle with cancer, she is interested in how individual perceptions of the body are formed. Her work also engages with themes such as the environment, illness, medicine, myth, feminism and motherhood. Her artist’s statement for “Instant Motherhood” is a moving reflection on the circumstances that lead to an individual becoming a mother, and the give-and-take nature of a mother-child relationship.

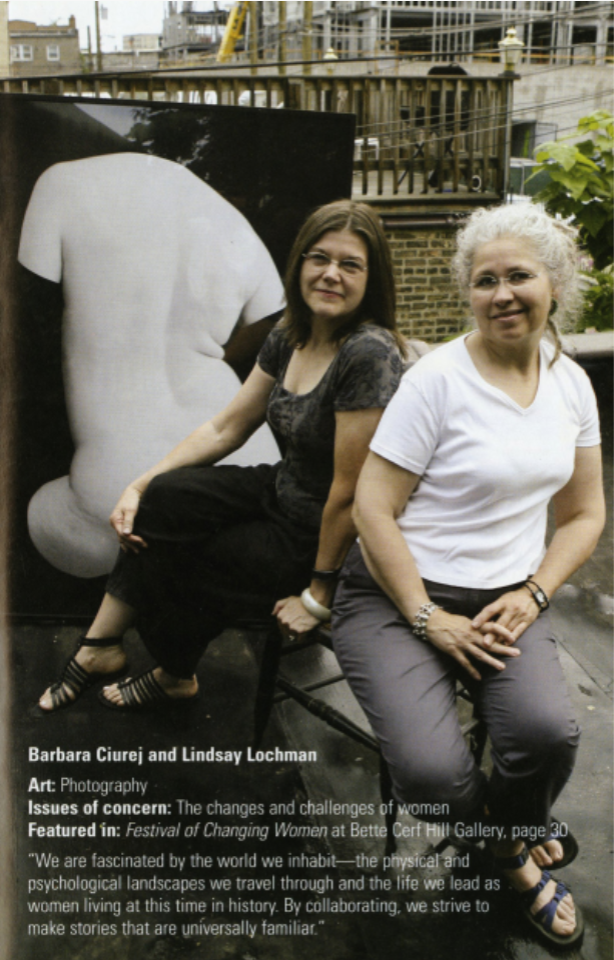

Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman are fine art photographers who have collaborated on photography since 1978. Their work explores feminist themes and landscapes, physical and psychological. During the Festival of Changing Women held in 2008, Ciurej and Lochman exhibited original prints to trace the contemporary experiences of women.

“Instant motherhood” by Lindsay Obermeyer. Women and Leadership Archives.

“Festival of Changing Women” exhibit catalog. Women and Leadership Archives.

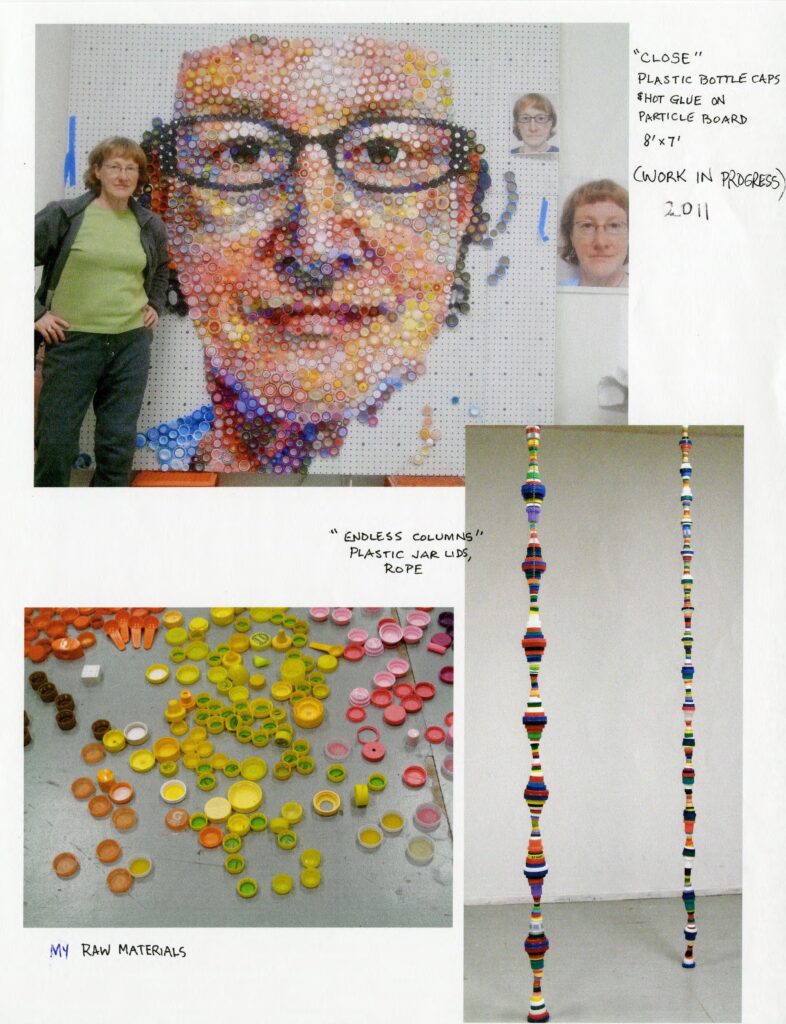

Self-portraits

Mary Ellen Croteau and Susan Sensemann utilized self-portraits as a medium for considering environmental issues and gothic narrative structures respectively. Describing herself as “a radical feminist and artist” who “sees [her] work as social criticism”, Croteau’s early paintings exposed and critiqued patriarchy and sexism. Her later works were interested in revealing the large amounts of trash humans produce and its harmful impacts on the environment. To demonstrate this, Croteau worked with non-recyclable human trash such as plastic caps and plastic bags to create work such as this self-portrait.

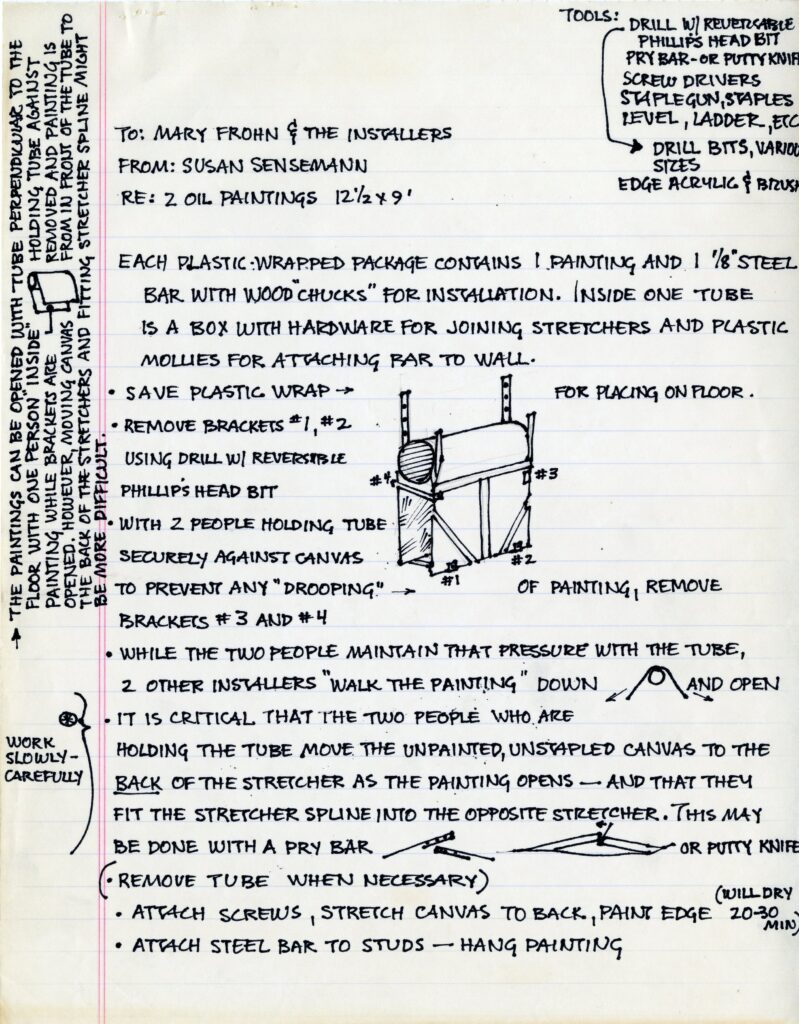

Susan Sensemann is an artist, educator (for more on her international lectures, see this blog post) and arts administrator whose work engages with a variety of subjects. One of the pages of her publication, “Impersonations”, contained within the digital collection shows an example of Sensemann’s photomontages. The photomontages, composed of Sensemann’s self-portrait overlaid with other images, were used to explore the intertwining of feminist self-portraits with gothic narrative structures.

“Close” by Mary Ellen Croteau. Women and Leadership Archives.

“Flirt” by Susan Sensemann. Women and Leadership Archives.

Multi-culturalism

Multiculturalism is a prevalent theme in the works of Margot McMahon and Eileen Ryan. Margot McMahon is a sculptor whose work is committed to public art and community involvement. Some of McMahon’s works can be seen in the Chicago metropolitan area, such as in the suburb of Oak Park. The digital collection features “Just Plain Hardworking”, a multi-media, collaborative exhibit featuring ten Chicagoans who made historical contributions to the city. Individuals of different cultural and working backgrounds were featured, drawing attention to the myriad ways in which everyday lives have shaped the course of Chicago’s development.

Multi-media and photographic artist Eileen Ryan’s “Face the Street” exhibit is another instance of how artists use their work to draw attention to the multicultural threads woven through the fabric of Chicago’s urban landscape. Ryan was involved in coordinating the public art exhibit (held in Wicker Park, Chicago), which highlighted artists working in non-traditional art forms.

William Franklin McMahon, Margot McMahon (center), Franklin McMahon. Women and Leadership Archives.

“Face the Street” exhibit catalog. Women and Leadership Archives.

“Everyone must leave something behind”: Legacies

Ecological and technological concerns resonate through Jacqueline Moses’ and Mary Ellen Croteau’s pieces as they interrogate humankind’s legacies. Using imagery from photographs, Jacqueline Moses creates paintings to contemplate the legacies left for posterity. Some themes that Moses has explored include the costs of war and globalization and death.

Mary Ellen Croteau’s work, whose self-portrait was highlighted in an earlier section, explores this theme of legacy by looking at the impacts of human trash upon the environment. The painting “Van Gogh’s Bag” (probably referencing Van Gogh’s “Almond Blossoms”) brought a resigned chuckle – how many times has one glanced up at a tree only to find a specter-like plastic bag marring the view?

“Van Gogh’s Bag.” Women and Leadership Archives.

Jacqueline Moses’ artist catalog. Women and Leadership Archives.

Processing Information

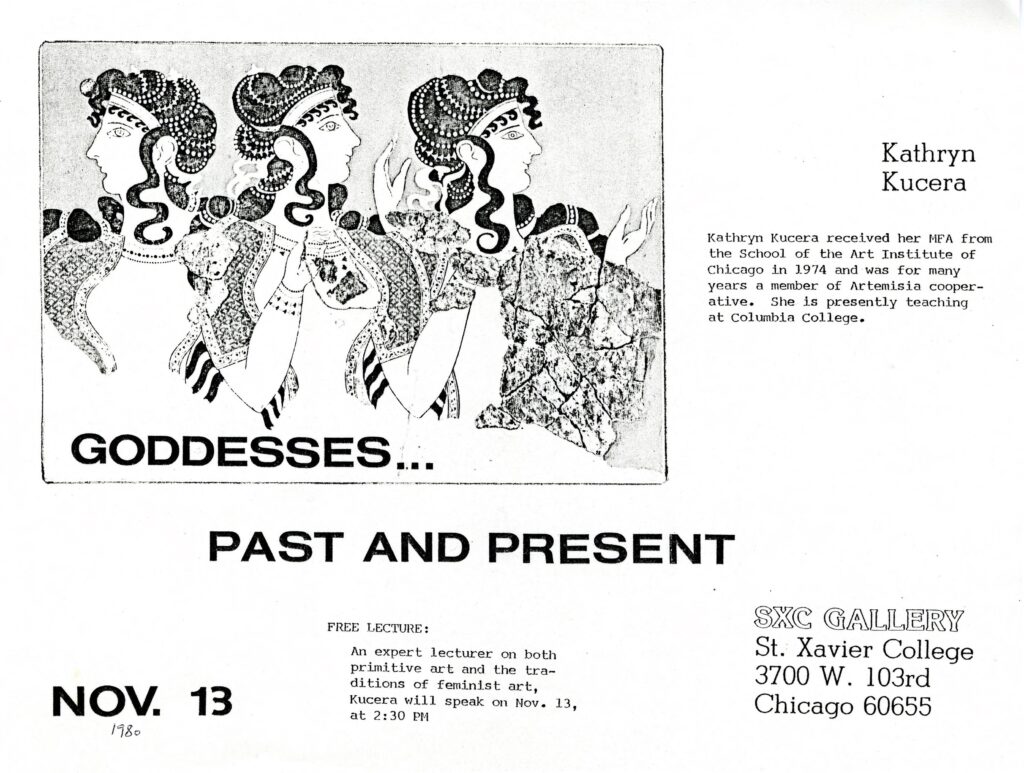

Every piece of art naturally carries and conveys information. However, our perceptions of a particular work are also shaped by the information surrounding it (its metadata, whether we see it on-site or virtually, etc.). Mary Tobin’s and Kathryn Kucera’s works engage with questions of how our perceptions are shaped and how the method of processing information affects our feelings.

Mary Tobin is a photographer who has exhibited at many institutions. There is an image in the digital collection showing a group of individuals wearing only bottoms, standing by something that was shiny. I was initially unable to make sense of it until I read the image title – “Untitled from Beach Series” – and understood that the shiny something was the sea. Research on her other work indicates her interest in considering how language structures our perceptions of the world. Perhaps my not being able to understand what an image was about until I read the title was part of the point. That is, language shapes how we process the other pieces of information it engages with.

Kathryn Kucera has shifted over time from the “more literal, painted human form” to “more metaphorical, dimensional pieces”. The “Another Story” exhibit catalog has images of collages Kucera made to present the “ambivalence, tension, [and] complexity of the accelerated pace of life today.” Kucera considers the collage an effective medium for contemplating how the bourgeoning of digital and paper images today has caused impressions to be processed in a fleeting manner.

“Untitled from Beach Series” by Mary Tobin. Women and Leadership Archives.

“Between Hatred and Desire” by Kathryn Kucera. Women and Leadership Archives.

The Chicago Arts Scene

Beyond being an overview of these artists’ careers, the digital collection also offers a glimpse into the ecosystem of the Chicago arts scene, enabling us to understand how artists interacted with one another and how the arts was cultivated in Chicago.

All the artists were affiliated with the Chicago-based women’s art cooperative, Artemisia Gallery (1973-2003), at some point during their careers. Before its closure in 2003, it was located at 700 N. Carpenter, Chicago, IL 60622. Named after the Italian baroque painter, Artemisia Gentilesch (an artist now widely regarded as a prodigy, but little acknowledged during her time), the gallery was founded in 1973 by a group of women artists who were disgruntled at the lack of opportunities for women artists. Envisioned as a space where artists could exhibit and discuss art, Artemisia played an instrumental role in nurturing the careers of local, national, and international artists. Reflecting on Artemisia’s influence upon her career, Susan Sensemann, Professor Emerita at the University of Illinois – Chicago (UIC), gives it credit for her promotion to full professor. Artemisia also had a mentorship program, of which Sensemann was a part.

Exhibition card with Artemisia Gallery’s address. Women and Leadership Archives.

“The Annunciation” by Mary Ellen Croteau, displayed at Artemisia Gallery. Women and Leadership Archives.

A discussion of the Chicago arts scene would be incomplete without considering other crucial elements such as exhibition logistics and art classes. The types of documents contained within “Visions: A Highlight of Chicago Women Artists” give us snippets of that tale.

Fliers calling for submissions reveal the types of opportunities available for artists to exhibit their work. Event fliers indicate where events were held, providing a useful tool for mapping art spaces in Chicago. Correspondence traces the interactions between institutions and individual artists. Aside from these, other fascinating documents show lesser-known details such as the topics taught in arts classes and installation techniques.

Interpreting art is not intuitive. While exploring the collection, I found myself frequently stumped at what a particular work was trying to convey and had to turn often to the artists’ statements for some help. But apart from thinking about the meaning of a work, I also began to pay attention to how a work made me feel. Was a work disturbing? Engaging? Frustrating? Why? The process was a reminder that art is an ongoing conversation between artist and viewer(s), all holding different perceptions of the world. And when more voices are added to the mix, the conversation grows richer.

A recent donation, the papers of Judith Roth (1935-2019), a Chicago-based visual artist who also created window displays for Marshall Field’s, is a prime example of how new collections enrich existing conversations. Roth was the founder of the first Ravenswood ArtWalk (which began in 2002), an annual event in which members of the public can explore art spaces in Ravenswood and learn about the community’s culture and history. The Ravenswood ArtWalk certainly reminds me of Eileen Ryan’s “Face the Street” exhibit mentioned above. I would be curious to know how these two community arts initiatives differed from each other and how they are part of a larger question on how such initiatives differ across different neighborhoods. This could in turn be part of an even larger conversation on how artists are possibly drawn to different neighborhoods based on the type of work the existing artist community engages in and how such concentrations form in the first place. The rabbit hole of research questions never ends!

Interested in delving into those conversations? The WLA has recently added several collections to its holdings and welcomes donations from women artists to enhance this area of collection focus. Check out the manuscript collections here and/or contact an archivist for more information!

Regina is a Sesquicentennial Scholar at the WLA and is in the second year of the Digital Humanities MA Program. Born and raised in Singapore, she enjoys reading, cooking, baking and figuring out how to keep her plants alive.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.