Piper Hall, 2005

Many visitors to Loyola’s campus and Piper Hall, where the WLA is located, are amazed by the beautiful white marble mansion and its incredible location on the shores of Lake Michigan. We are always answering questions about the history of the building as a home and as a library for Mundelein College. However, we do not often talk about how the house got its current name.

Like most buildings on university campuses, Piper Hall was given its name by important donors. In this case, Virginia Galvin Piper donated funds to Mundelein College and had the building named after her late husband, Kenneth Piper. The building was later renamed the Virginia G. and Kenneth M. Piper Hall in honor of the couple.

I myself had not given much thought to who these people were, until I came across several files in the Mundelein College collection containing correspondence, informational pamphlets, and a book written to share the life and legacy of Virginia G. Piper. In this book, I found a story more enthralling and inspiring than I ever imagined.

The story of Virginia Piper is intertwined with the story of Chicago. It has more human drama and heartache than a novel. There is romance, tragedy, transformation, and even a mysterious unsolved murder. Lucky for you, the text of the book, Devotedly Virginia, has also been put into a lovely website where you can read all of the challenges and triumphs of Virginia and the many individuals who shaped her life. Trust me, it is much more interesting than you might think.

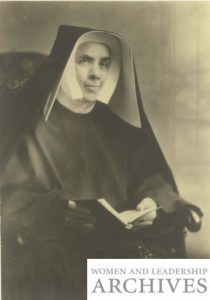

In this post, I would like to share some of the highlights of the story and add details about Virginia Piper’s relationship with Mundelein College and her deep friendship with the college’s longtime president, Sister Ann Ida Gannon.

Portrait of Virginia, 1965

Born in 1911, Virginia grew up with humble roots and a loving family. Her close relationships with her mother, her sister, her grandmother, and many female friends shaped the woman she became. As a young woman, she worked hard to help her parents through the Great Depression and did not marry until she was 33. This first marriage, to Motorola founder and public figure Paul Galvin, transformed her life. Along with love and happiness, the union led to Virginia’s conversion to Catholicism and her introduction to the world of philanthropy. When Paul died in 1959, Virginia chose to take control of the Paul V. Galvin Charitable Trust. This began her forty-year career as a philanthropist.

Virginia took her new position seriously. She met with bankers, stockbrokers, and financial advisors to learn everything she could about the job ahead of her. Her active involvement in every aspect of her charitable giving was unique at that time, especially for a woman.

According to Virginia’s biography, the remarkable woman’s relationship with Mundelein College began with a phone call to another remarkable woman, college president Sister Ann Ida Gannon, in 1964. Virginia likely saw Mundelein as a perfect fit for charitable gifts, as it shared the late Paul Galvin’s dedication to education and faith. The first gift recorded in the Mundelein records is a $300,000 donation to build a 350-seat auditorium in the college’s new Learning Resource Center. The Paul V. Galvin Memorial Hall was dedicated on October 30, 1969. At this event, Virginia introduced her friends at Mundelein to Kenneth Piper, a longtime friend and vice president of Motorola. The couple had fallen in love and were married later that year.

Galvin Hall Dedication

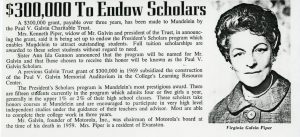

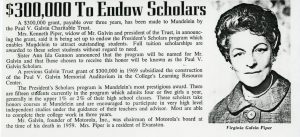

In 1972, it was announced that Virginia planned to give $300,000 to set up a scholarship endowment to provide full tuition scholarships to top students. The Mundelein records hold a number of letters Galvin Scholars wrote to Virginia updating her on their successes and thanking her for the role she played in their education.

Galvin Scholarship news, 1972

Even in times of personal transition, Virginia remembered Mundelein College. When she and Ken bought a home in Arizona where they would live most of the year, letters show that she gave her dining room furniture and Oriental rug to the college.

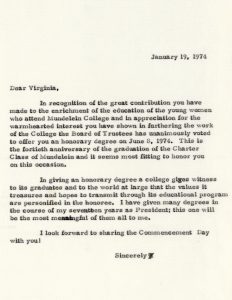

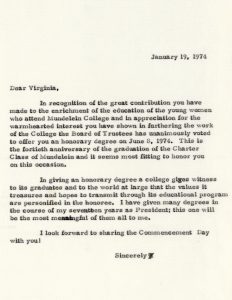

Mundelein recognized Virginia’s contributions to the college and many other causes by giving her an Honorary Degree at the 1974 Commencement ceremony. On June 8, a memorial mass was held for Paul Galvin in Galvin Hall before the Pipers and their friends attended the Commencement where Virginia was honored. Many letters from Virginia, Ken, and other friends describe the special day and the gratitude they felt for the experience.

Honorary degree letter, 1974

Ken Piper was a great supporter of Virginia’s work. Letters between Virginia and Sr. Ann Ida reveal that Ken worked “so diligently and hopefully” on plans for a Women’s Executive Institute at Mundelein that he would support. Unfortunately, Ken passed away suddenly in January of 1975 before these plans could be realized. Sr. Ann Ida flew to Arizona as soon as she could and stayed by Virginia’s side for 10 days to help her through the difficult time, a testament to their strong bond.

Virginia lived another 24 years after losing her second husband and dedicated the rest of her life to her work. Just eight months after Ken’s death, Virginia returned to Mundelein College for the dedication of the Kenneth M. Piper Hall, Center for the Study of Religious Education.

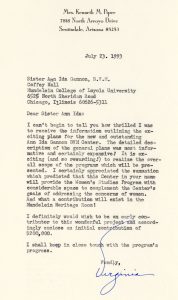

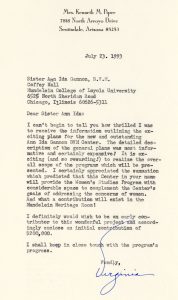

Virginia continued to give to Mundelein for scholarships and other projects. After the affiliation with Loyola, she took great interest in the plans for a women’s center to carry on Mundelein’s legacy. She was one of the first donors to the Gannon Center for Women and Leadership and continued to give generously to the project that was named after her dear friend.

Gannon donation letter, 1993

Virginia Piper and Sr. Ann Ida continued their friendship through letters, phone calls, and frequent visits until Virginia’s death in 1999. Her last gifts and those given by the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust after her death went towards renovations to Piper Hall. At the rededication of the white mansion by the lake in 2004, the new home of the Gannon Center and Women and Leadership Archives was renamed to reflect the generosity of both Virginia and Kenneth Piper.

Over 50 years after she began supporting the education of women at Mundelein, Loyola students and the community are still benefiting from Virginia Piper’s contributions. Virginia did not attend Mundelein or grow up in the Catholic faith or have any other personal connections to the school. When looking for projects to support, she saw the potential and the value she was looking for in Mundelein College. And today, when we look at this woman who contributed so much to the growth of Mundelein College, we see someone who embodied the strength, leadership, compassion, and grace that the small Catholic women’s college strove to instill in each of its students.

Learn more about Virginia Galvin Piper’s life and philanthropic work through Devotedly, Virginia and The Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust, which continues her work. You can also learn more about her relationship to Sr. Ann Ida Gannon and Mundelein College at the Women and Leadership Archives.

You can tour Piper Hall yourself during Open House Chicago on October 13, 2018!

Caroline is a Project Archivist at the WLA currently processing the Mundelein College Records. She is a graduate of the Public History Masters Program at Loyola University of Chicago.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.

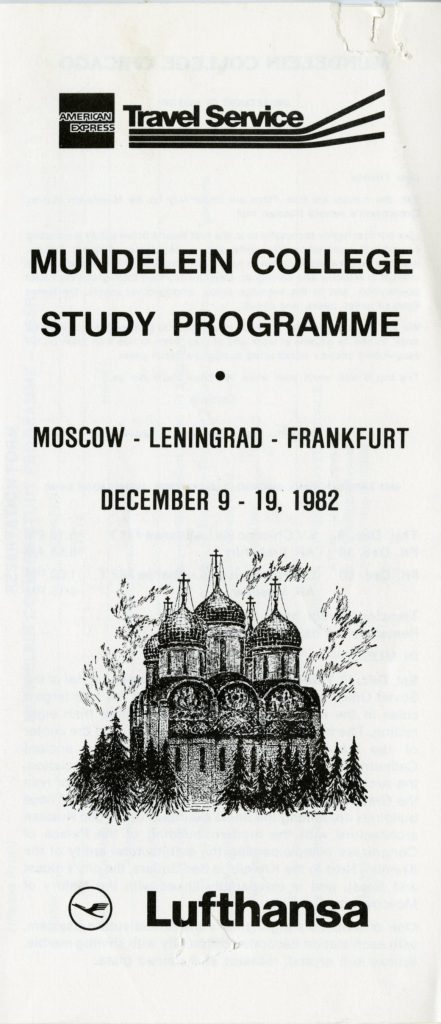

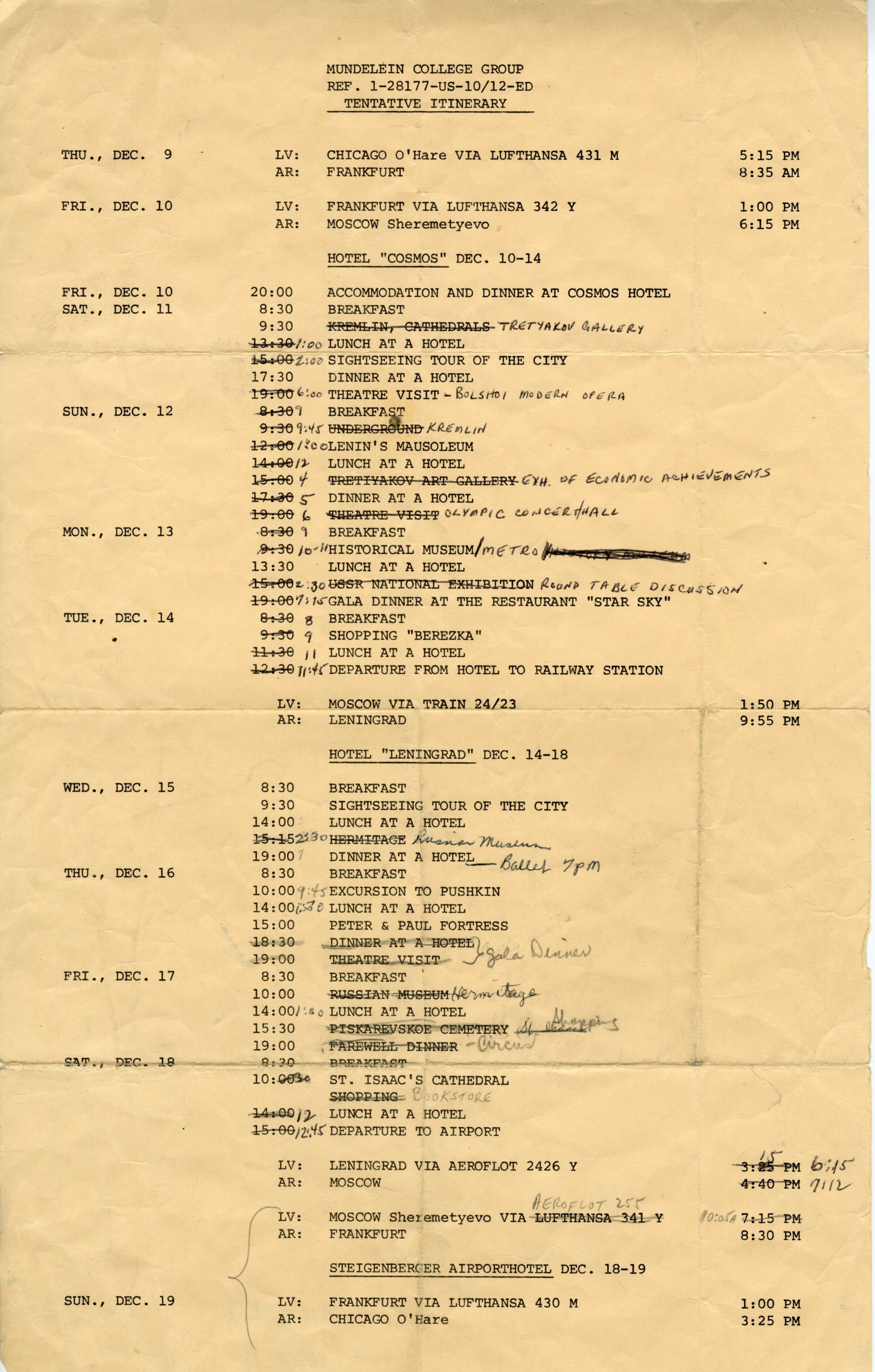

Ora was busy packing her bags for the trip. She had to fit everything she needed for the ten-day trip, but she was not worried about space; she was worried about getting through Soviet customs. Ora, and forty-three other students, alumnae, and friends of Mundelein College* were preparing for a study abroad trip to the Soviet Union in December of 1982. Shortly after Mundelein planned the trip the Chicago Action for Soviet Jewry (CASJ) contacted Ora and other participants of the study abroad trip. The organization asked the students to help them deliver gifts and religious material to “Refusenik” families in the Soviet Union.

Ora was busy packing her bags for the trip. She had to fit everything she needed for the ten-day trip, but she was not worried about space; she was worried about getting through Soviet customs. Ora, and forty-three other students, alumnae, and friends of Mundelein College* were preparing for a study abroad trip to the Soviet Union in December of 1982. Shortly after Mundelein planned the trip the Chicago Action for Soviet Jewry (CASJ) contacted Ora and other participants of the study abroad trip. The organization asked the students to help them deliver gifts and religious material to “Refusenik” families in the Soviet Union.

On the last day of the trip, the students made contact with the family in Leningrad. They only had one hour to visit before they had to catch their flight back to the United States. The Leningrad family, much like the family in Moscow, were very welcoming to the Americans. Their four-year-old daughter showed off her English skills, reciting children’s rhymes her father had taught her. After visiting for an hour and distributing the gifts, Ora and her classmate departed for the hotel to pack their things for the trip home. All the students and alumnae made it safely back to the United States despite smuggling contraband into the Soviet Union and breaking several Soviet laws.

On the last day of the trip, the students made contact with the family in Leningrad. They only had one hour to visit before they had to catch their flight back to the United States. The Leningrad family, much like the family in Moscow, were very welcoming to the Americans. Their four-year-old daughter showed off her English skills, reciting children’s rhymes her father had taught her. After visiting for an hour and distributing the gifts, Ora and her classmate departed for the hotel to pack their things for the trip home. All the students and alumnae made it safely back to the United States despite smuggling contraband into the Soviet Union and breaking several Soviet laws.

Bruce, pictured here, is the current canine porter and guardian of the door for the author of this

Bruce, pictured here, is the current canine porter and guardian of the door for the author of this