Last spring, the WLA Director informed the Graduate Assistants that we would be receiving a lesson in folding textiles. Great, I thought, someone will finally give me the secret to folding a fitted sheet! Unfortunately, a neat linen closet still eludes me. However, I did gain an important skill for archivists and public historians working with collections. While archives are mainly thought of as repositories for historic papers, several of our collections include various fabric objects. It is important to know how to care for these textiles so that they can be preserved for researchers for as long as possible.

So, I would like to pass on to you the basics of caring for textiles in the archives.

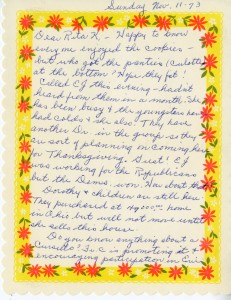

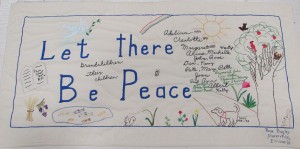

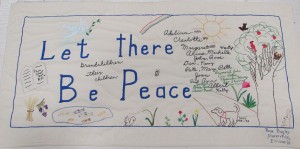

A Peace ribbon embroidered by Rose Bagley

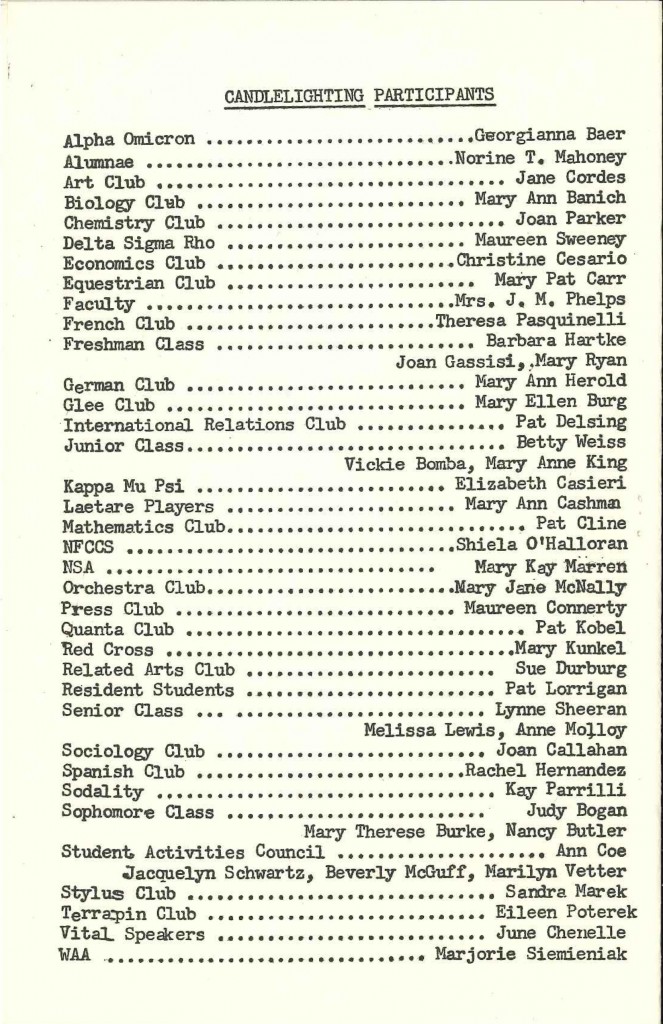

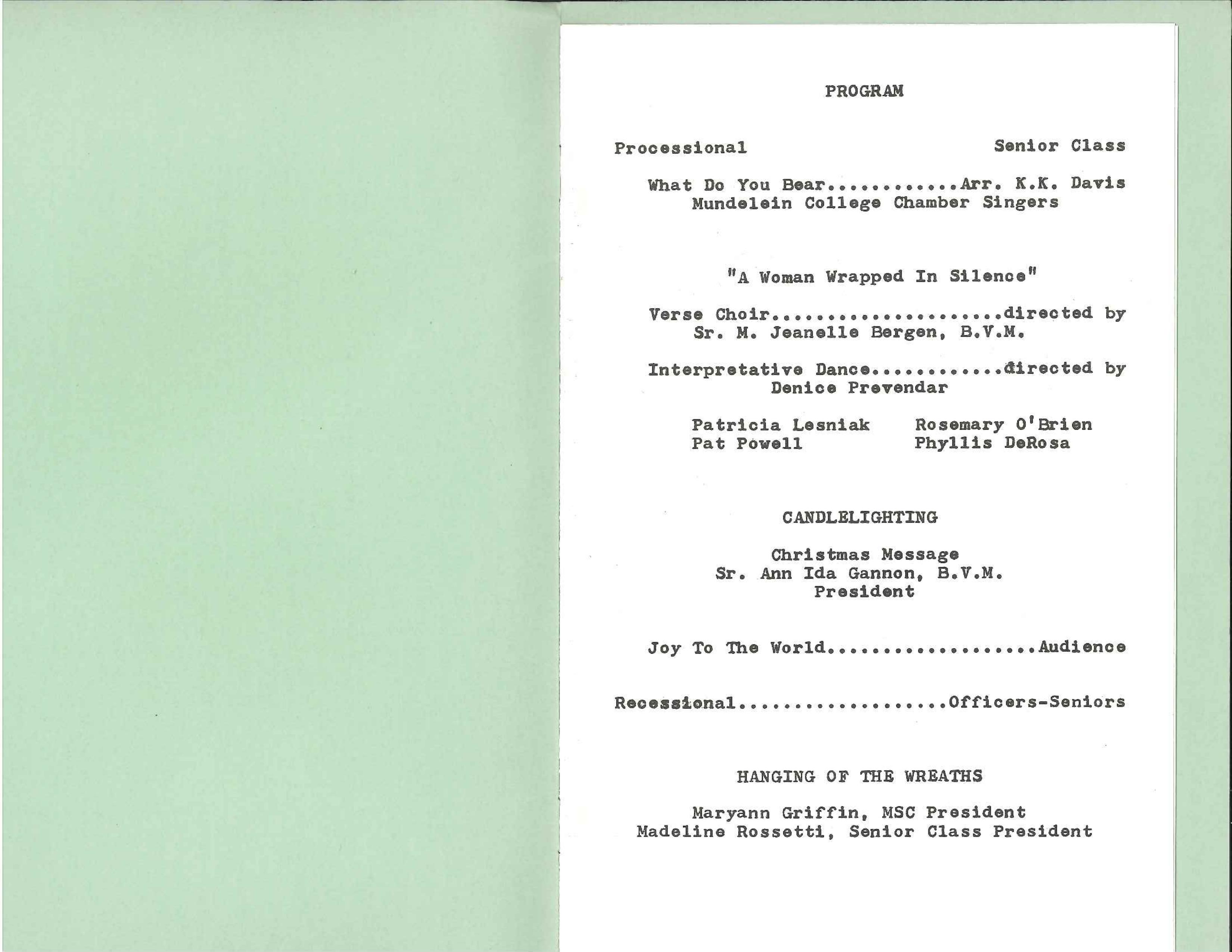

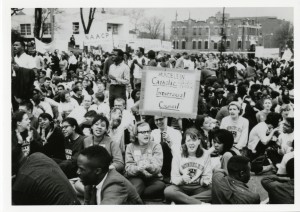

The textiles we were working with were donations from Rose Bagley, whose collection has not yet been processed. Rose participated in organizing for the Peace Ribbon event on August 4, 1985. On that day, an estimated 15,000 people carried a 15 mile long ribbon that wrapped around the Pentagon, the Washington Monument, and Capitol Hill to protest nuclear weapons. The ribbon was made up of 36×18 inch segments decorated with paint, embroidery, and sewing and sent to Washington from all over the country. Our collection includes just some of the over 1,300 segments that were sent from Illinois.

Garments and other textiles with more complex construction would require more careful consideration. While I will be focusing on flat storage of textiles, some items may require a different form of storage. However, these simple, rectangular banners can help us get a feel for the techniques of textile conservation.

Wait, why do I even care?

Imagine it’s laundry day and you’re folding up your t-shirts and putting them into a drawer. When you pull a t-shirt out a week or two later to wear it, there are creases where the folds were that you try to shake out or iron away. Now imagine if that t-shirt sat in the drawer for 25 years, 50 years, a hundred years. The fabric at those folds has been stretched and pressed for that length of time, causing damage and breakage to the fibers.

Because of the perils of sharp folds, the method of storing historic textiles revolves around creating as few folds as possible. Where folds must be made, we try to reduce the strain that creases put on the fibers.

Supplies needed:

- Acid free, lignin-free archival boxes

- Acid-free, lignin-free, unbuffered tissue paper (lots of it)

- Cotton gloves

- A large work space

Step One: Every box has a tissue lining.

Prepare the box in which your textiles will live by lining it with tissue paper. The goal is to have the artifacts only touching tissue paper, not any part of the box or other objects.

Step Two: Best laid plans

Wearing your gloves, lay the first textile flat on a clean surface. When moving textiles, be sure to lift carefully from both ends in a way that does not put strain on any part of the fabric. Use a cloth underneath as support or get help from a colleague for large, heavy objects. Your textiles may not be delicate now, but we still want to treat them carefully.

With your object flat and your box nearby, plan out the best way to fold the textile. Remember, you want the item to fit into the box with as few folds as possible.

Step Three: Time to make sausage

Once you know how you will fold your textile, you must pad these folds in order to reduce strain on the fibers. The formal archival term for this padding is a sausage.

To begin making your sausage, take two or three rectangular pieces of tissue paper and crinkle them up like a kid opening a birthday present. Well, maybe not that violently. Next, pull the now messy paper back out into rectangles. Here, you may choose between two methods. You can roughly pleat your paper like an accordion, or you can loosely roll the paper. Either way, you should end up with a sausage-shaped roll of tissue paper. You may want to slightly twist the ends to keep your sausage from coming apart. Delicious.

The goal in sausage-making is to make the tissue paper full and crush-resistant.

Step Four: Know when to fold ‘em

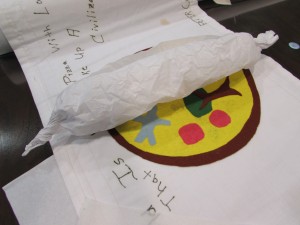

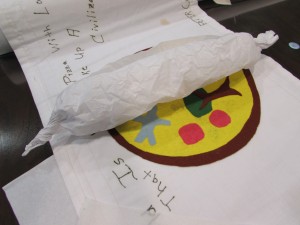

An accordion-style sausage in place

A rolled sausage

Place your sausage where it is needed on the textile and fold the fabric over. Gently push the sausage into the fold so that there are no sharp creases. Depending on the width of your textile, you may need to add another sausage or two to insure that the fold is padded all the way to the edges. Maybe you’ll need some mini sausages.

For garments, you will also need to use tissue paper to puff out bodices, sleeves and ruffles. Some sources also suggest that you use cardboard tubes, covered in tissue paper, to support folds in heavier fabrics.

Step Five: Think inside the box

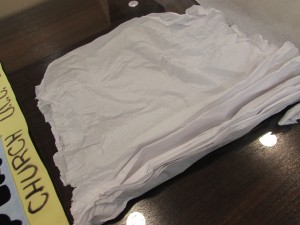

Carefully move your textile into the box and readjust your sausages as needed. Cover the textile with a layer of tissue paper.

Surrounded by tissue paper, the final peace ribbon banner goes into the box.

For the sake of space, it is likely that you will need to put multiple items in a box. Avoid stacking heavy fabrics that will crush the folds of items underneath. Never crush your sausages. Because our peace ribbons were fairly light and only had one fold, we found that we could put five in each box without putting too much weight on the folded banners.

Be sure to put tissue paper in between each item in the box.

When you have placed the last textile in the box, cover it with, you guessed it, more tissue paper, and fold any overhanging paper over the textiles. Be sure that you have not overfilled the box and that your carefully puffed textiles will not be crushed as you put the top on the box.

It is recommended that textiles be repacked and refolded regularly, perhaps annually. This gives you an opportunity to put new fluffy sausages and change where the folds are located so that no area of the textile is under perpetual stress.

Committing to Textiles

Recently, another donor asked the WLA if it would like to take a donation of over 100 more peace ribbon segments. When packed as described above, with five to a box, this donation would take up a considerable amount of shelf space (as well as a parade float’s worth of tissue paper). Archives often face the decision of whether they can take donations like this and properly care for them. Will these objects be more valuable to researchers than potential future donations that could fill this space? Archivist job requirement: predicting the future.

This basic lesson on caring for textiles does not cover all of the procedures that may be needed with different types of textiles. However, my practice with the peace ribbons gave me an understanding of the problems that must be considered for this type of artifact.

For more information on textile conservation, see this in-depth guide from the National Park Service.

For guides on caring for textiles at home, take a look at the links below.

Guide to storing antique textiles from the Smithsonian Encyclopedia

Textile Care guide from the International Quilt Study Center and Museum

Caring for Your Heirloom Textiles is a thorough article from Marjorie M. Baker at the University of Kentucky

Caroline is a Graduate Assistant at the WLA and is working on her Master’s in Public History at Loyola University Chicago. When not scrapbooking, she spends her spare time exploring Chicago, interpreting dreams and watching cheesy movies with her husband.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.

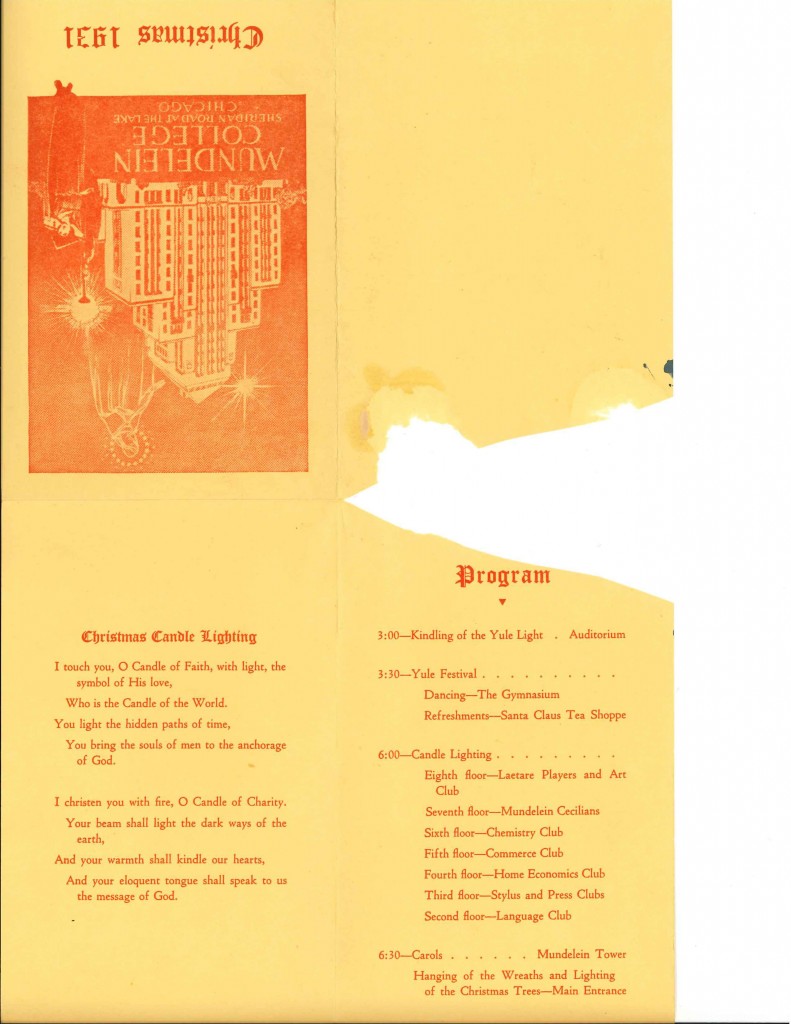

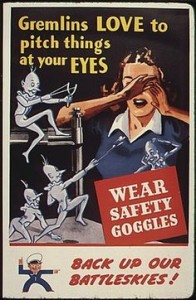

Social media has become an important and valuable tool for cultural institutions such as archives, libraries, and museums. Technology has changed the way people seek information and relate to the world around them. This means that archives that make connecting with the public a priority must stay informed with how their audience is communicating and get creative with their outreach.At the WLA, we use this blog and our Facebook page, along with our website, to share news and cool things from the archives in order to inform the community about the useful and interesting collections we have here.

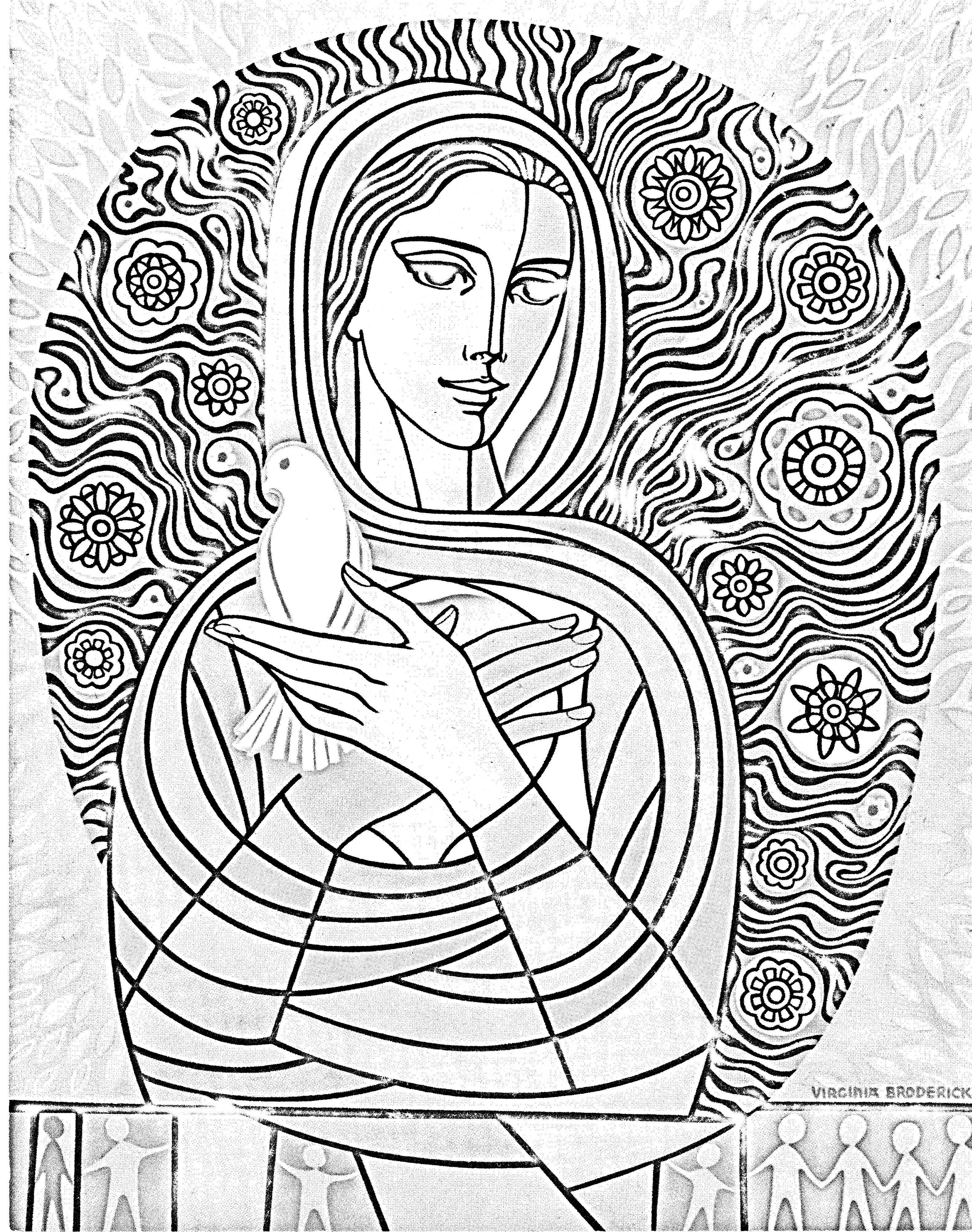

Social media has become an important and valuable tool for cultural institutions such as archives, libraries, and museums. Technology has changed the way people seek information and relate to the world around them. This means that archives that make connecting with the public a priority must stay informed with how their audience is communicating and get creative with their outreach.At the WLA, we use this blog and our Facebook page, along with our website, to share news and cool things from the archives in order to inform the community about the useful and interesting collections we have here. Virginia Broderick coloring page

Virginia Broderick coloring page Mercedes McCambridge coloring page

Mercedes McCambridge coloring page