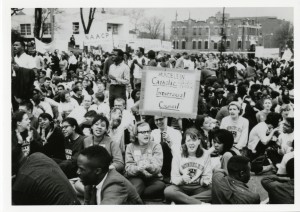

For the past few months we have been researching Mundelein College’s role in the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama as well as the march itself in preparation for the anniversary and the accompanying events this March. After researching Selma, writing blog posts and web features, and attending related events at Loyola, we wanted to use Selma as a starting point to talk about broader issues of race, gender, and representation in archives and elsewhere.

JENNY: Within our archives Selma is a challenging topic to research. Although we have historic persons as well as organizations who participated in Selma and other events of the Civil Rights movement, the vast majority of material is photographs. Small amounts of other material that relates to the history of the civil rights movement can be found – but is generally integrated into other collections such as Mundelein College and that of scholar Suellen Hoy. These two collections contain relevant material on Selma, but also represent other important strengths of the Archives, particularly the history of women in the field of education.

Despite our many strengths, like every historical institution, the WLA has gaps. When thinking of this for our collections, we do not have much material that relates to hispanic women and there is also little that relates to the history and presence of various Asian populations in the midwest.

MOLLIE: But how do you even begin to collect? We don’t have a slew of people knocking down our door desperate to donate their personal papers or organization’s records on a daily basis. Many people don’t even know that archives, much less the WLA, exist. Often class or educational levels can play a role in a person’s knowledge of archives, which could lead to somewhat homogenous donors and collections. How can archivists reach out to fill in these gaps?

Mahalia Jackson, 1962. Photo by Carl Van Vechten. Carl Van Vechten photograph collection, Library of Congress.

JENNY: Taking inspiration from the Civil Rights movement, who are some Black women leaders or activists in the Civil Rights movement who could be part of ours or another archive’s collections? Why have I not learned about them? Take for example, Mahalia Jackson. Born New Orleans in 1926, Jackson was a nationally-renowned gospel singer who worked for 40 years in the music industry. She also actively participated in the Civil Rights movement, singing at multiple national rallies and events, but this portion of her history is overshadowed. I found Jackson’s page on Wikipedia, as well as entries on biography and music history sites. Much of the information I found was brief, noting two to three paragraphs of accomplishments and referencing her association with more publicly known figures of the Civil Rights movement. Wikipedia’s page has background on her childhood and youth, her career, her activism in the Civil Rights movement, as well as her death and legacy.

MOLLIE: Although Mahalia Jackson has a pretty decent Wikipedia page in terms of length, it is by no means complete. But unlike many other women, she actually has a page, which let Jenny learn about her in the first place. Like almost all Wikipedia articles about women, Jackson’s article is subject to gender bias. In the section on her Civil Rights activism, the article focuses on her relationships with Ralph Abernathy and Martin Luther King, Jr. rather on how Jackson herself contributed to the movement. Gender bias on Wikipedia can take many forms ranging from total exclusion of women to a bias in the way the article is written.

Archives are spaces where stories like Jackson’s reside, but they are also places of interaction. We want visitors to come and engage with, look at, touch (when appropriate), and discover the materials in our collections. But because barriers (getting there, navigating the finding aids, finding the time etc) often restrict people from engaging one-on-one with the collections, we have to ask ourselves how to tell the stories of the women in the archives. With Selma, we told the story of Mundelein College and their role in the march. Public programs contextualized the stories found in the archives while blog posts and web features made it available to a wider audience. But did we tell a complete story? Did we tell a good story? As an institution that collects and makes available women’s stories, gender bias issues found on Wikipedia are not as much of an issue for us.

At the March 12th Mundelein Remembers Selma event, panelists reached out beyond Mundelein’s story to talk about broader issues of race, gender, and religion during the 1960s and participants in the march recounted their personal experiences. Was it a good story? Yes – it was engaging and interesting. Was it complete? No. But no story can be one hundred percent complete and coherent. Archivists and public historians need to acknowledge the gaps in their collections and stories and work to close them through exhibits, general interactions with visitors, or Wikipedia edit-a-thons.

Jennifer is a Graduate Assistant at the Women and Leadership Archives. She will be graduating in May 2015 with a M.A. degree in Public History. In her spare time she enjoys stumbling upon public art and reorganizing her apartment.

Mollie is a Graduate Assistant at the WLA and is finishing her last semester of her MA in Public History at Loyola University Chicago. In addition to sharing authority, she enjoys biking, making/eating pie, and playing the musical saw.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.