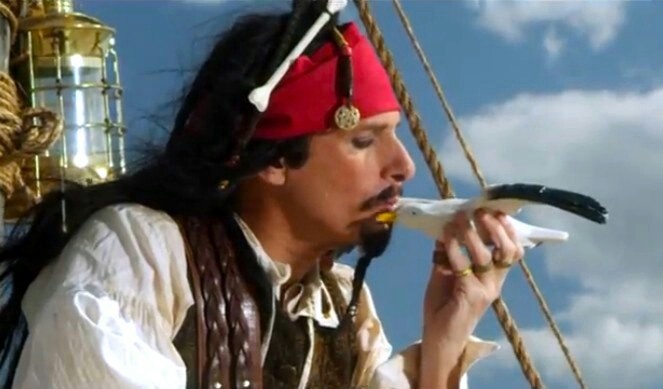

Being an archivist is like being a pirate. Just hear me out on this one.

Popular images of pirates depict them as adventurers navigating the high seas on the search for hidden treasure. Although archivists don’t tend to engage in swashbuckling, or get scurvy (because eww), they do get to explore collections in order to discover the “riches” inherent to every collection. Plus, they have to find a way to share that treasure with the world. That’s where the similarities pretty much end.

To help find that treasure, pirates use treasure maps. For the archivist, the equivalent to the treasure map is…the processing plan!

To help find that treasure, pirates use treasure maps. For the archivist, the equivalent to the treasure map is…the processing plan!

Okay the name’s not exciting, but processing plans are beautiful, beautiful things! When an archives receives a donation, the records are not usually perfectly organized — already prepared to transplant into boxes and immediately perfect for public viewing. When an archivist creates a processing plan, they lay down a model for how the record should be organized so that the records can be accessed by researchers that come to the archives. Processing plans allow archivists to think critically about what is contained in a collection, but plans also make them consider how that information should be displayed so that researchers are able to easily find what they need. See? Treasure map. My inner Virgo that loves order and cleanliness rejoices.

Every archives is unique, so elements within the processing plan may differ depending on the collection itself or the organizational strategies that are put in place by an institution’s archivist. In my opinion, there are three major elements that should appear in all processing plans. There are multiple subheadings that I think go beneath each of these major themes– I will go into some suggestions for each below:

1. Current State: This is the place in the processing plan devoted to describing (you guessed it) how the collection currently exists, including any information regarding the accession information, how the collection was donated, how it appears to be ordered, and the biographical sketch/organization information that will be used to create a summary of the collection for the finding aid. This is also where the processing plan should underscore the scope and content of a collection, or an inventory of sorts of what documents appear in the collection. Generally a more detailed summary appears when you are suggesting an arrangement, but the scope and content is great for a big picture of what is contained in the collection. Here is a great example from the Harvard University wiki:

EXAMPLE: The papers of My Best Friend include travel diaries, family scrapbooks, personal and professional correspondence, photographs, 23 audiotapes and 45 disks.

2. Arrangement: As suggested above, this is where the real organization happens. In the arrangement section of a processing plan, the scope and content is broken down into specific individual series as well as notes for how items within the series should be arranged. Harvard University continues the My Best Friend example below:

2. Arrangement: As suggested above, this is where the real organization happens. In the arrangement section of a processing plan, the scope and content is broken down into specific individual series as well as notes for how items within the series should be arranged. Harvard University continues the My Best Friend example below:

EXAMPLE: Series I. Biographical and Personal (4 cartons)

Series II. Diaries (7 cartons)

Series III. Correspondence (12 cartons)

Series IV. Writings (3 cartons, 2 file boxes)

Series V. Photographs (6 cartons, 8 folio boxes)

Each series as shown above would include information about the specific documents, photos, correspondence, etc. as well as the rough dates. Specificity is key in this component. The more in depth this section is, the easier the ensuing organization will be. It’s worth mentioning that you should always get to know the collection inside and out before beginning the processing plan. If you only glance through each section, you are not ready to organize all of the elements. It is worth taking a few hours or days depending on the collection’s size to see what is in the collection as well as how that collection is already organized. In the world of archives, the process of learning the collection before arranging it is referred to as intellectual control.

3. Work Summary: This section is pretty self-explanatory. This section is a good place to establish a checklist of what exact work needs to be done in order to complete the processing of the collection. Some questions this section should answer are, “What kind of supplies will I need to preserve the collection? Is there anything that needs separate storage? When should the finding aid be completed? What tasks can I delegate to students/interns?” This section would also be a good place to discuss how long the collection will take to process as well as the supplies needed for when the collection is available to be moved into folders and archival boxes.

The three elements listed above are a very rough outline of what might be contained in a very general processing plan. The link above shows a fantastic template Harvard University supplied on their wiki page. It absolutely bears repeating. You can find it here.

In summary, the processing plan is your friend. Detailed organization at the onset of the processing procedure makes all the difference in the world between organizational bliss and utter frustration. Want to know more? The Society of American Archivists has a fantastic book available on their website called How to Manage Processing in Archives and Special Collections. I know what I’m putting on my x-mas list!

Ellen is a Graduate Assistant at the WLA and is in the first year of her M.A in Public History at Loyola University Chicago. Before moving to Chicago, Ellen was a Kindergarten teacher in Louisiana. She enjoys brunch, procedural dramas, and pugs.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.