Though Father’s Day may still be a couple months away, I’d like to use this post to celebrate a special organization that existed at Mundelein College* during the 1950s and early 1960s: the Mundelein College Fathers Club.

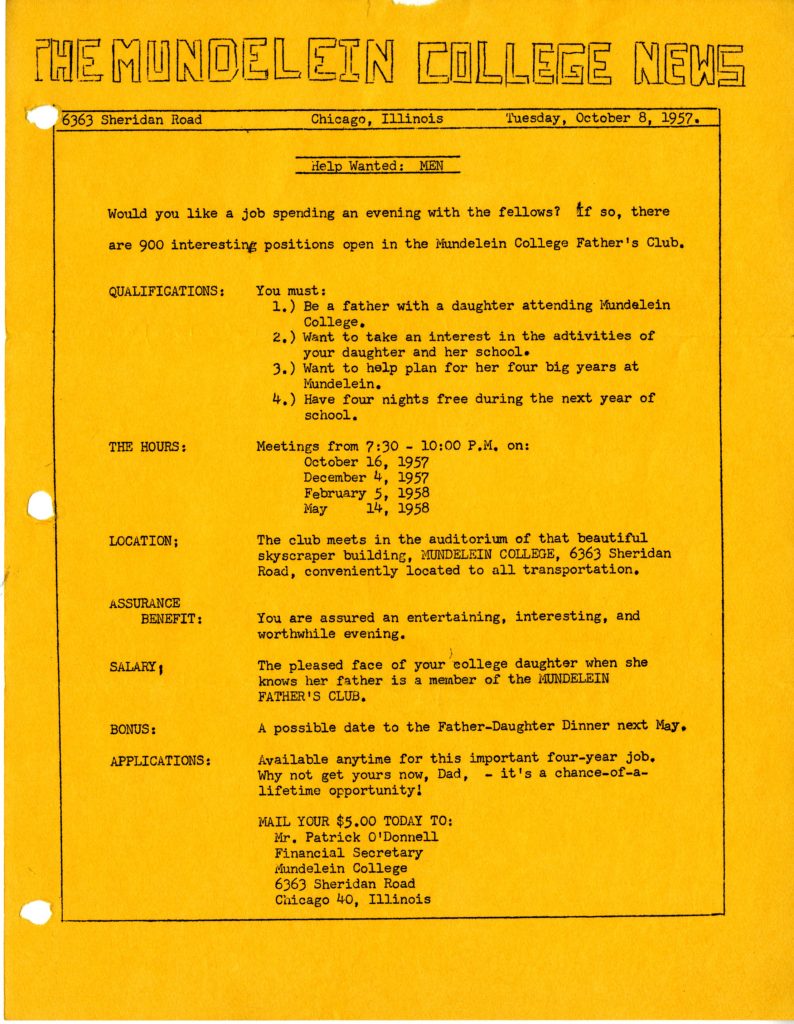

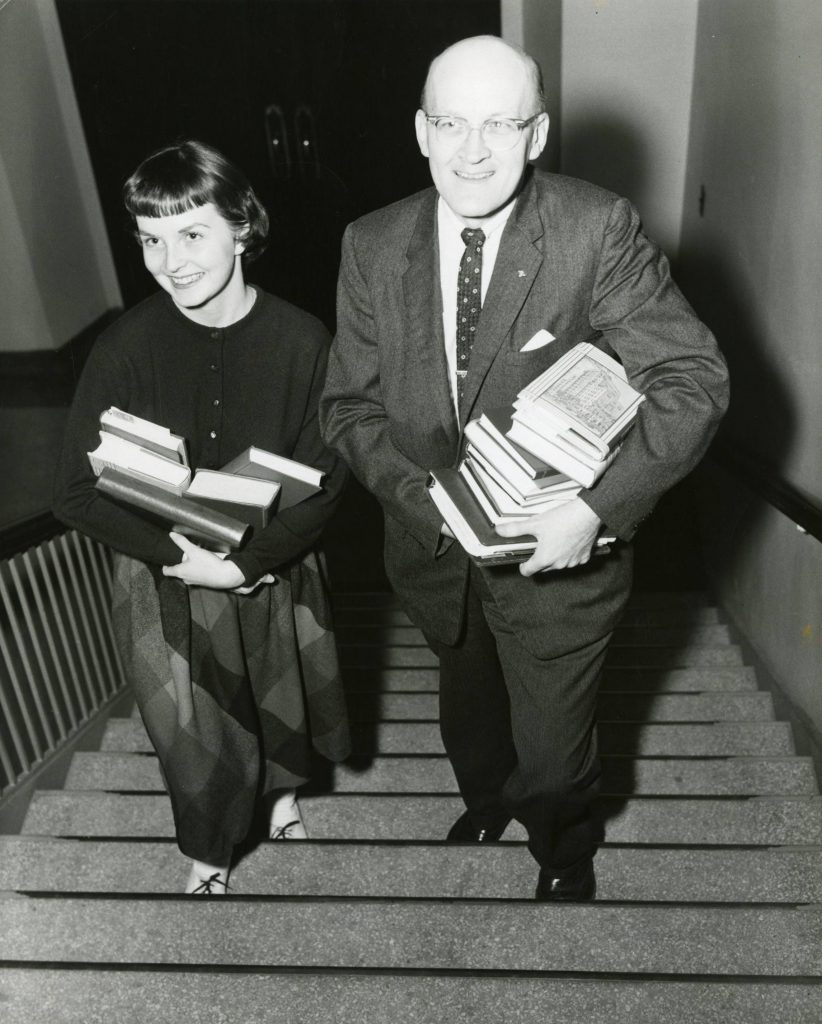

Founded in the spring of 1952, the organization was formed by fathers of Mundelein students to support the College and administration. Edwin B. Parkes, Chairman of the inaugural Club Membership Committee, described it this way: “We know of no better way to gain recognition for our girls and the Sisters than by organizing and using our talents. Individually we can do little, but collectively we can accomplish the results desired.” Through membership dues and fundraising events, these dedicated dads raised funds to rehabilitate the school buildings, including modernizing the classroom light systems, updating the convent section of Mundelein, and otherwise assisting with building upkeep. In 1961 they funded the purchase of closed circuit television equipment to be used for educational purposes. They also provided scholarships and loans to students in need.

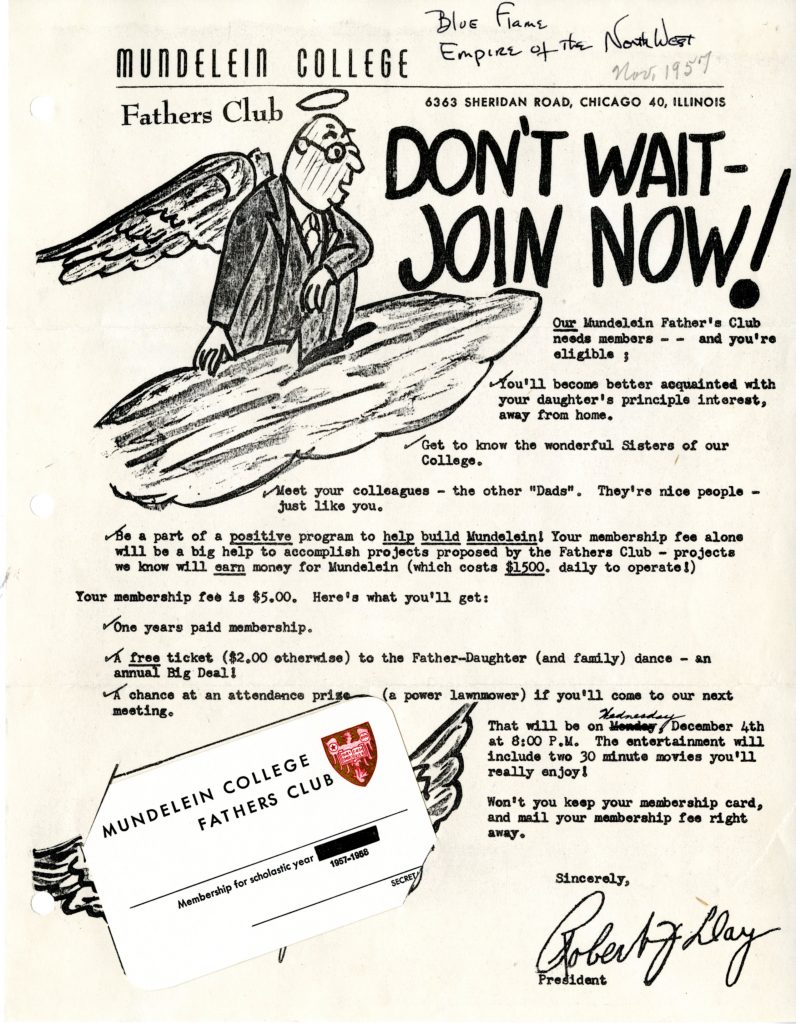

Just as important as their good works was the club’s mission to providing opportunities for fun, social get-togethers for their members. They planned opportunities not only for Mundelein fathers to meet and get to know one another, but also so that fathers and daughters could spend meaningful time together during the college years. For the dads, each club meeting included some form of entertainment after the business was concluded. These included some stereotypical, 1950s male interests – such as lectures from a criminal cases columnist from the Chicago Tribune, an FBI agent, a popular sports editor at the Chicago Daily News, and film showings on such subjects as the inner workings of the Stock Exchange, traffic patterns, the Baseball World Series, and one called “Blue Flame” that chronicled the story of natural gas from well head to consumer. At a meeting in 1960 they arranged to put in a long distance call to the Air Force Base in Colorado Springs, where they were able to ask questions of an Air Force Officer about the country’s defense system.

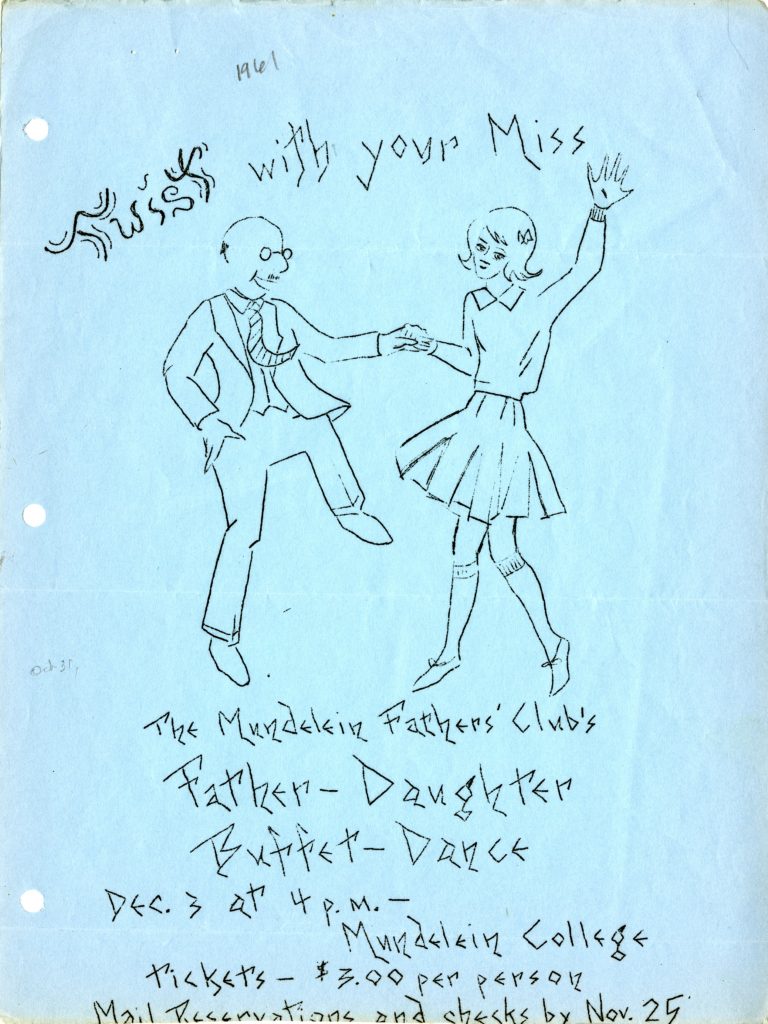

One of the signature events for the club was their annual Father-Daughter Dinner-Dance. Though it went through a few name and venue changes, the basic idea stayed the same; an evening of father and daughter bonding over music and food. A 1962 club membership letter told fathers that participation in events, like the Father-Daughter Buffet-Dance, “demonstrates to her [their daughter] that I am interested in her, her teachers, and in what she learns.”

As any educator will tell you, investment from a student’s parents or guardians in their education can make a world of difference in how that student feels about and does at school. Hat’s off to this dedicated group of dads (and who often worked alongside the “Women’s Auxiliary”, the Mundelein Mother’s group) to support their daughter’s college experience. To see how the Fathers Club tradition has lived on, check out the Loyola Parent’s page.

*Mundelein College, founded and operated by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM), provided education to women from 1930 until 1991, when it affiliated with Loyola University Chicago.

Kate is a Graduate Assistant at the WLA and in the first year of her M.A. in Public History at Loyola University Chicago. A Colorado gal, she enjoys classic films, bike riding, and all things museums.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.