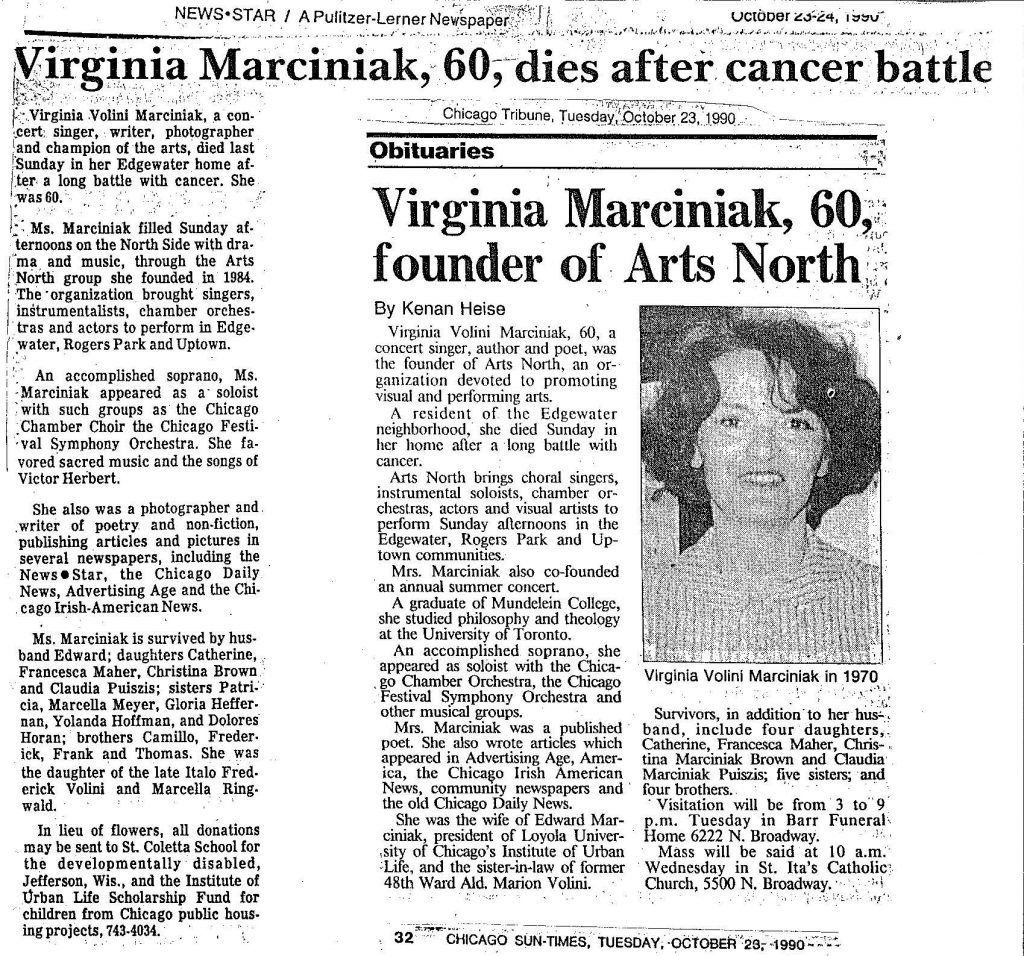

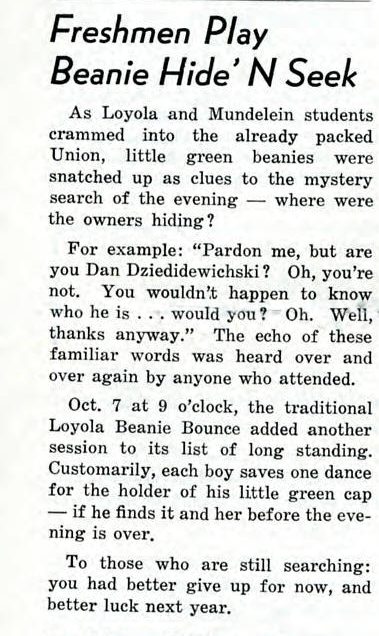

When my husband and I refer to ourselves as dinks and high five, we are celebrating the fact that our status as a “Double Income No Kids” household means we can spend a little more time and money on our current whims and less worrying about finding affordable rent in a Chicago neighborhood with good schools (is this even possible?). When I found the term “dink” on an old green song sheet in the Mundelein College Records, I was pretty sure that the students of the 1940s meant something different.

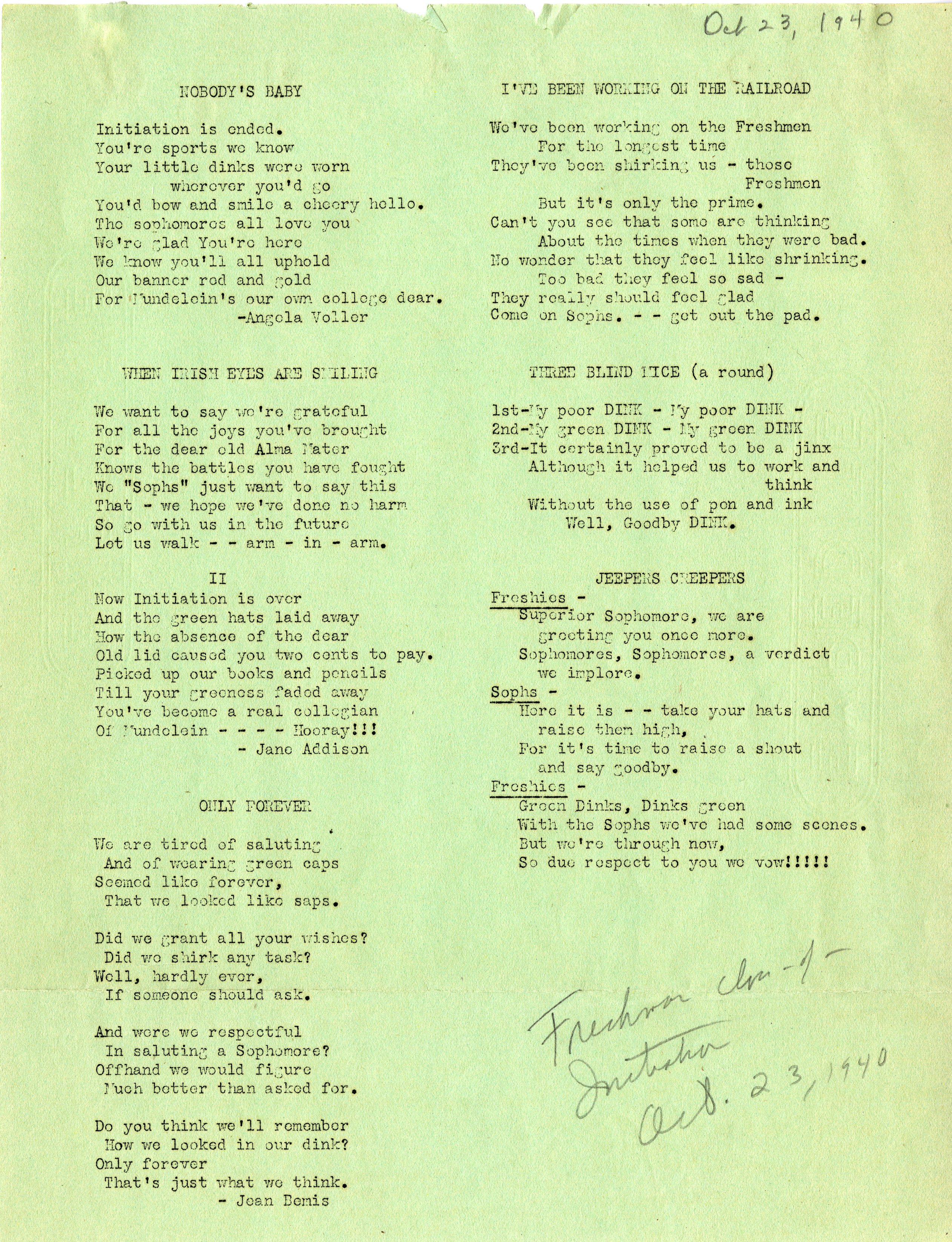

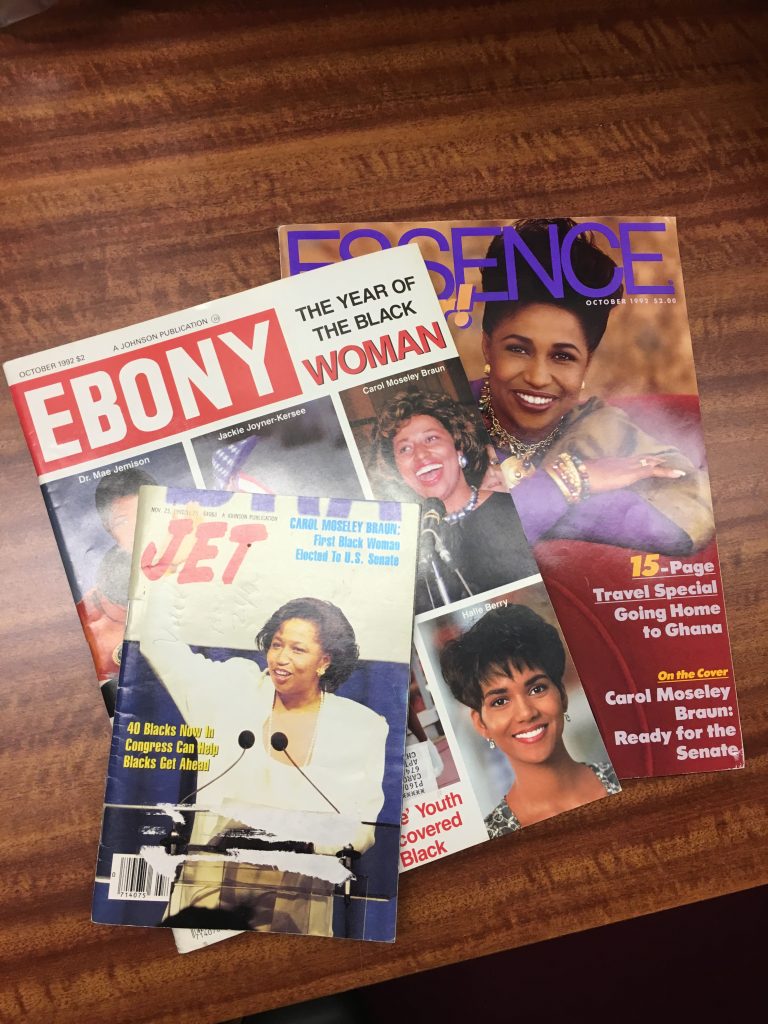

This song sheet from the 1940 Freshman Initiation event features many songs referencing “dinks”.

The songs written and sung for a freshman initiation event hint at the meaning of “dink” and its significance in introducing new students to college life. However, a search of the Mundelein student newspaper, The Skyscraper, failed to bring up a single article giving me more information.

Naturally, I turned to Google to see if this strange term was used in other colleges of the time. I soon found many articles about an interesting tradition that I had never heard of.

Dinks Across the Country

A dink on the 20th century American college campus referred to a beanie cap, often green, worn by freshmen to distinguish them as the newbies. An article on the Penn State University website says that upperclassmen voted in 1906 to require freshmen to wear their dinks at all times on campus and at school events. Freshmen were expected to tip their green caps to upperclassmen and could be subjected to embarrassing hazing if caught without their dinks. Similar antics occurred at many schools in the East and Midwest. In most cases, women on co-ed campuses were not included in the dink tradition, at least at first. Female students at Penn State wore green ribbons in their hair before donning the dink with their male peers in 1954.

The Ohio State University Archives created a fun digital exhibit dedicated to the various freshman beanie traditions found in the colleges of the Big 10. In theory, the beanie was intended to promote school spirit and bonding among freshmen. However, it seems like the real bonding of Ohio State freshmen may have come more from a shared fear of being caught without your beanie by the group of juniors authorized by the Student Senate and the President of the University to throw beanie-less freshman into a nearby lake. It is obvious the beanie did not represent camaraderie to the wearers, as students gathered at the end of their freshman year for the annual “Cap Bonfire.”

In most cases, the cap customs came to an end in the 1960s. However, the tradition lives on in a more benevolent form at Hood College in Maryland. Each class at Hood is given a different color beanie so that the caps are used beyond the initiation period to proudly distinguish each graduating class.

At Hood College, junior students in yellow beanies welcome freshmen students of the class of 2020 by presenting them with blue beanies at the 2016 Convocation. Photo courtesy of Hood College.

Dinks at Mundelein

Finding details of the use of the “dink” at Mundelein College was more difficult than my Google search. Although I found a few signs of dinks and beanies being worn by freshmen, the scarcity of information leads me to believe that this was not a continuous tradition at Mundelein. I found a few photos of students wearing the little caps, often at freshman events. However, most photos of freshman picnics and orientations show bareheaded young ladies, so the requirement to wear the cap must have been a rare and unenforced ritual.

Analyzing the songs from 1940 gives us a good bit of information about what the dinks meant at that time. The green hats were worn at all times by the freshmen for some period of time at the beginning of their first semester. Freshmen were expected to give a salute when encountering upperclassmen and perform other tasks. Getting caught without your dink would cost you 2 cents. No wonder the freshmen are singing of how glad they are to remove their caps..

Members of Big Sisters chat at Mundelein College in the 1950s. Are the two students in beanies their freshmen “Little Sisters”?

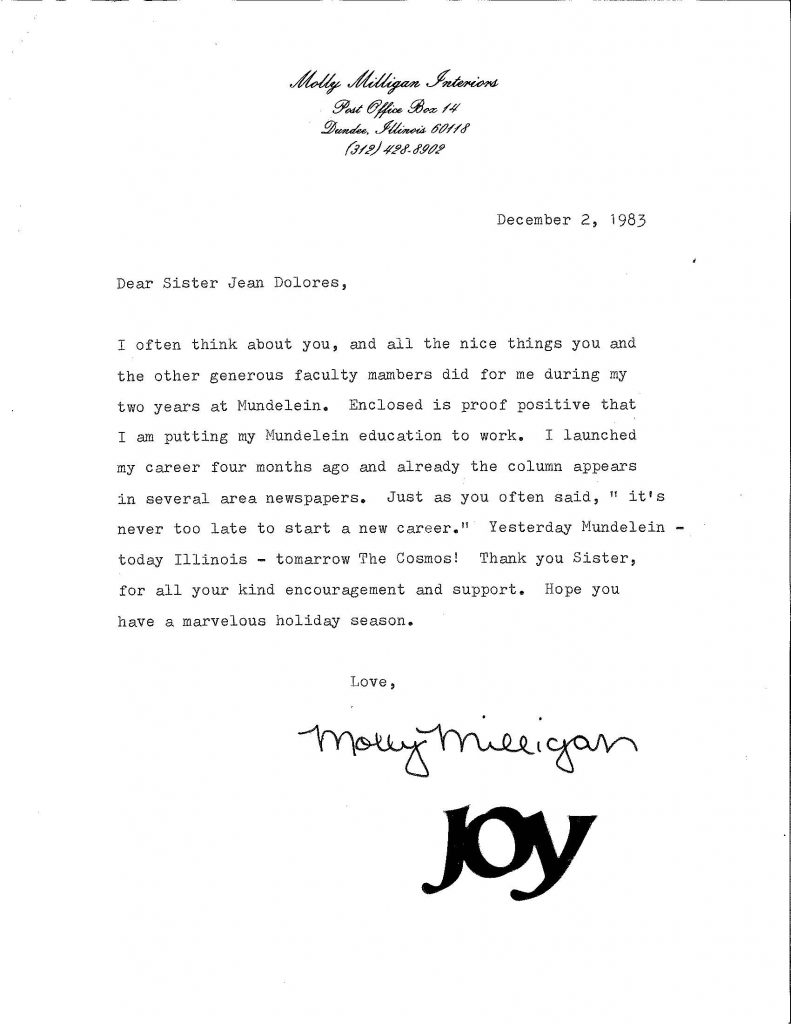

Most references to the freshman beanie at Mundelein are in connection with the Big Sisters organization. The Big Sisters were nominated sophomores and juniors who took on the job of welcoming and mentoring the incoming freshman class, adopting “Little Sisters” to guide individually. Another song sheet from the Big Sister’s Mardi Gras Tea on February 25, 1941 refers to the green dinks that the “Freshies” wore in their first semester.

“Remember the days—

You were but Freshies green,

And dinks you wore

Which made you quite serene.

Freshies, then and still—

But now Sisters too,

My pledge I renew- faithful to you—

I give you my word.”

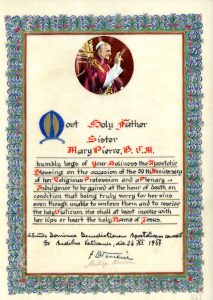

Whether or not the young pupils actually felt “serene” in their beanies, the records of the Big Sisters point to good intentions of the upperclassmen to use the beanies to identify and offer friendship to new students. An article in the Skyscraper from 1965 mentions that freshmen were given their “traditional red beanies” by the Big Sisters at a reception during orientation week. This description of the red beanie matches up with the one real piece of evidence we have that was recently donated to the collection. By this time, the beanies seem to be more about school spirit and a welcome to the community than about calling attention to the “greenness” of the freshies.

This felt “dink” in Mundelein College colors is the only one in the collection and was likely worn in the 1960s.

The top-ranking freshmen of 1966 pose in their Mundelein beanies. This is the only photo we have of a group of freshmen all wearing their caps.

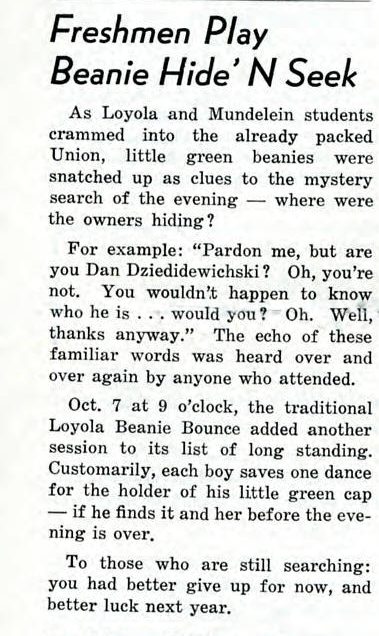

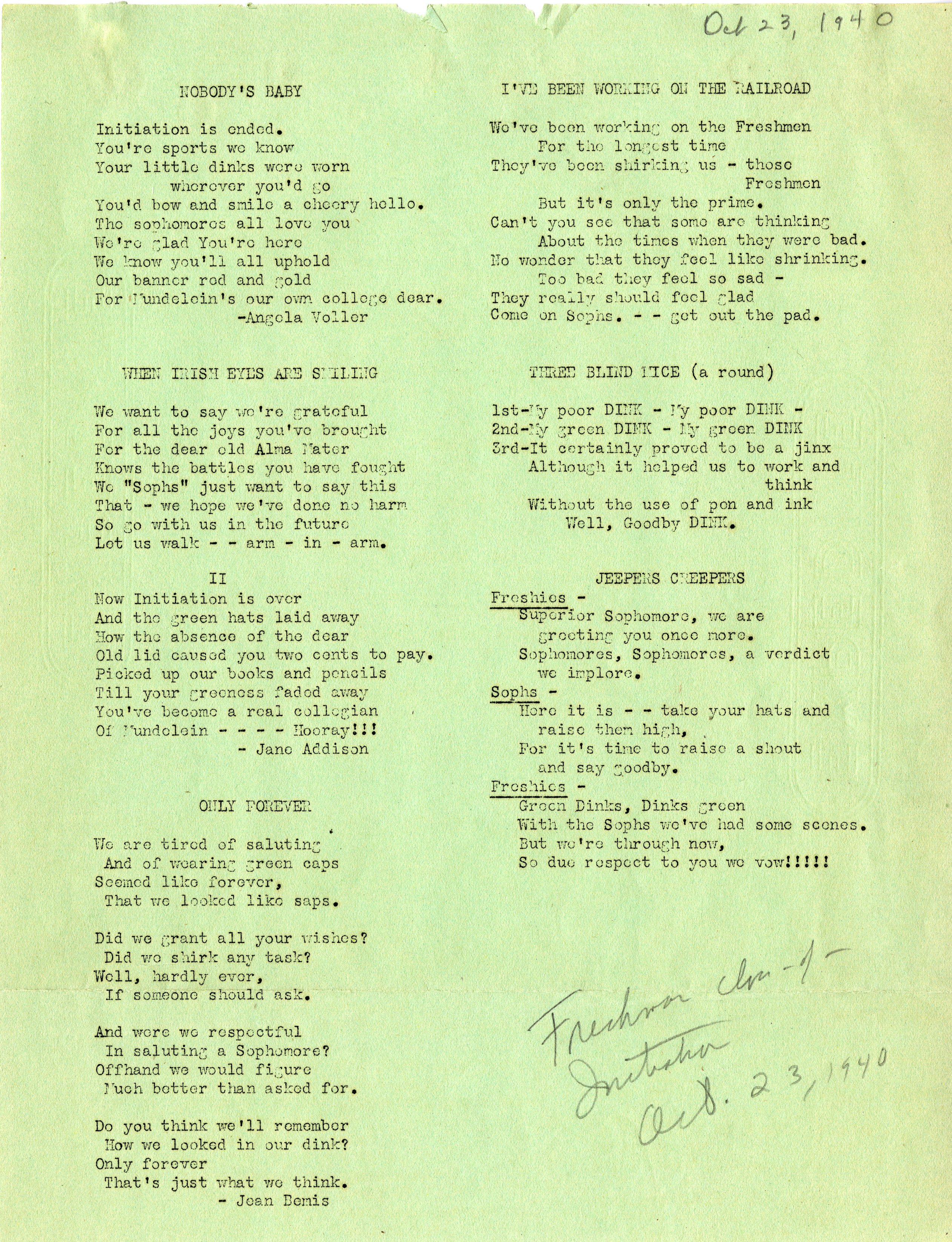

I found one other way that the green dink impacted life on the Mundelein campus and it relates to the boys next door. From 1949 to 1961, freshmen students from Loyola University and Mundelein College came together at the beginning of the fall semester for a mixer they called the “Beanie Bounce.” The dance, sometimes hosted by Loyola and sometimes planned jointly by both student activities councils, officially introduced the new freshmen to their neighboring students. In early years of the dance, each Loyola boy would give his beanie to a Mundelein lady in the course of the night, but a Skyscraper article from 1960 describes how the game evolved over the years.

Loyola freshmen Joe Doody and Jim Whiting demonstrate the Beanie Bounce tradition, passing their green caps to Mundelein freshmen twins Rita and Louise Kozak at the 1953 dance.

A Skyscraper article from October 19, 1960 recounts the activities of the “Beanie Bounce” on Loyolas Campus.

A 1984 photo of Mundelein College freshmen at orientation shows three students wearing white and red beanies, a sign that the love for the little hats continued in some form for many years.

Three Mundelein College freshmen proudly sport little white caps at freshman orientation in 1984.

I remember being a scared freshman and can’t imagine the added anxiety associated with the dink hazing traditions. However, when used as a symbol of welcoming the next generation into the college community, its hard not to get nostalgic for the chic little freshmen caps. I vote school bookstores add the vintage felt beanies to their shelves of sporty caps.

Did you have a dink at your alma mater? Are you a Mundelein alumna with a memory of the beanies? We would love to hear your stories and see your photos!

Caroline is a Project Archivist at the WLA currently processing the Mundelein College Records. She is a graduate of the Public History Masters Program at Loyola University of Chicago. Caroline has a talent for looking good in almost any hat, but always forgets to wear them.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.