Thanksgiving is here and I’m sure we will all spend time this week reflecting on how thankful we are for our homes, families, and an abundance of food. During World War II, Americans definitely did not take any of these for granted, including the food on their tables. When the United States entered the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor, rationing on foodstuffs and other consumer goods began almost immediately as the economy shifted to military production.

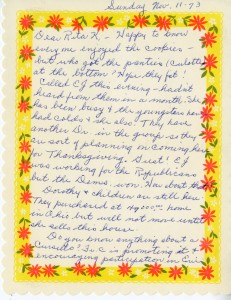

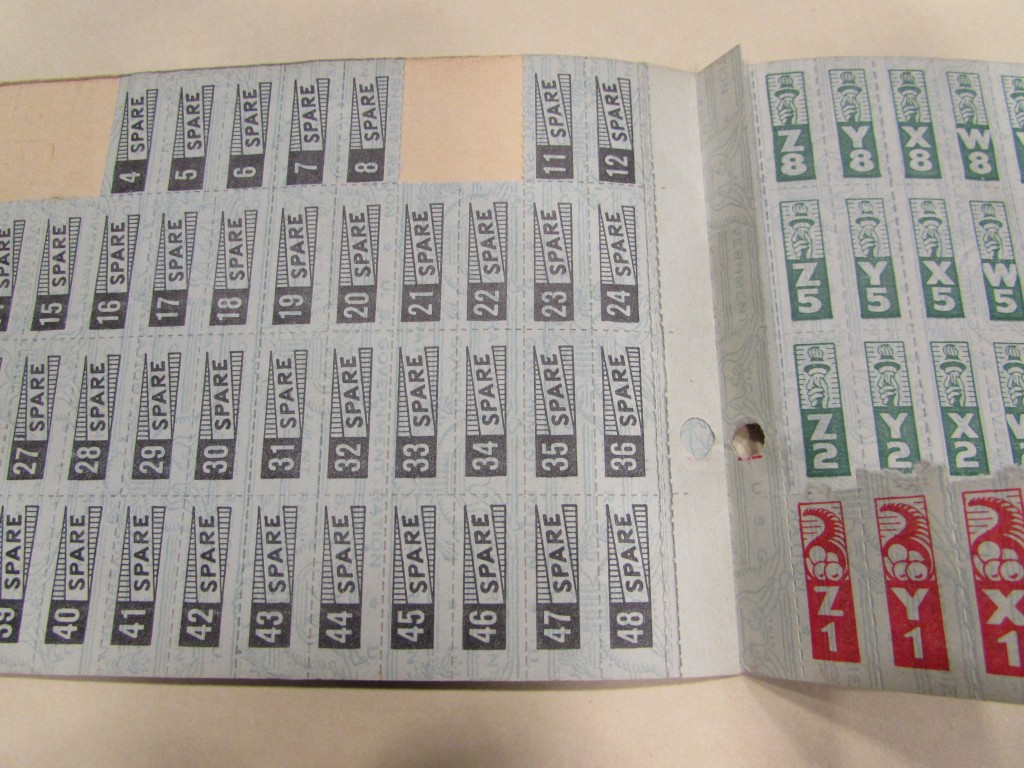

Americans were given ration books like this monthly and used the stamps when purchasing rationed goods. Once a person ran out of stamps, they could not buy any more of that item that month. This war ration book is from the collection of Eleanor Risteen Gordon.

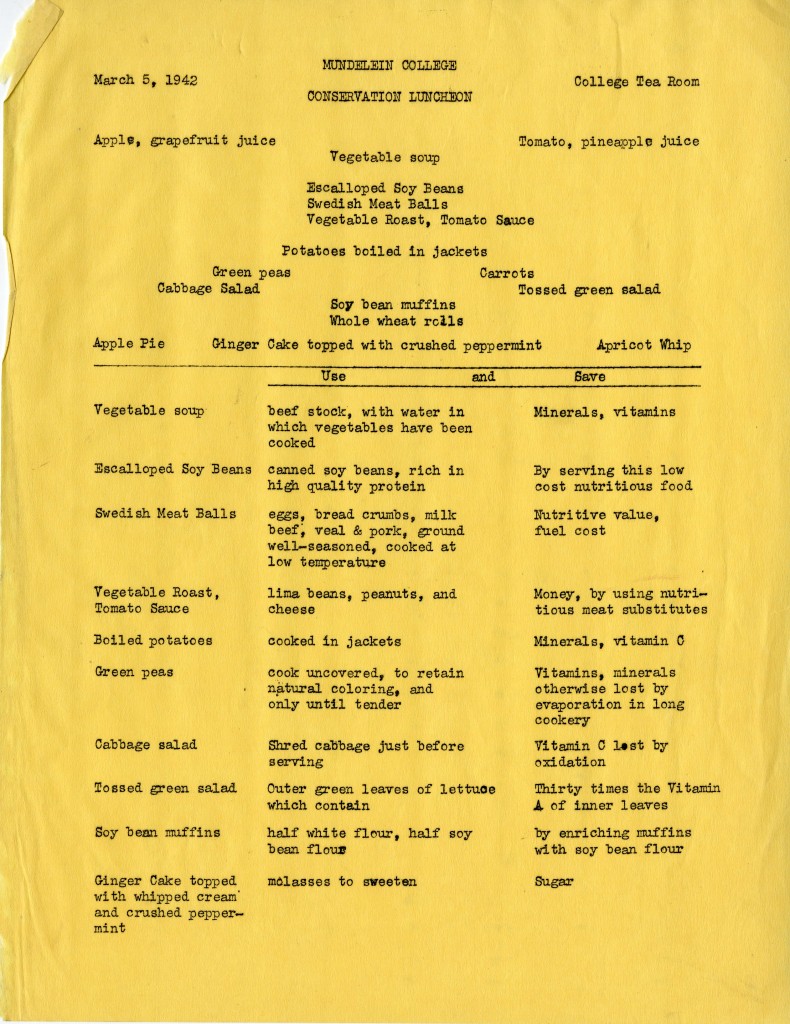

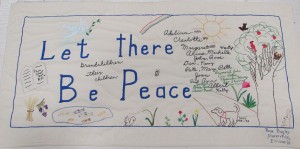

In 1942, Mundelein students took part in building a wartime garden on campus to grow fruits and vegetables for the college. These “victory gardens” were planted by Americans all over the country during World War II (as they were during WWI) to aid the war effort by reducing the pressure on food supplies. Food acquired new importance as Americans dealt with limitations and found pride in their ability to support the troops from their own backyards. Along with growing food for the school, the Mundelein Department of Home Economics wanted to find ways to help families in the community make nutritious and affordable meals with minimal need for the rationed ingredients. The department held a Conservation Lunch on March 5, 1942, where students shared ways to adjust popular recipes to use substitutions for rationed ingredients and make dishes healthier.

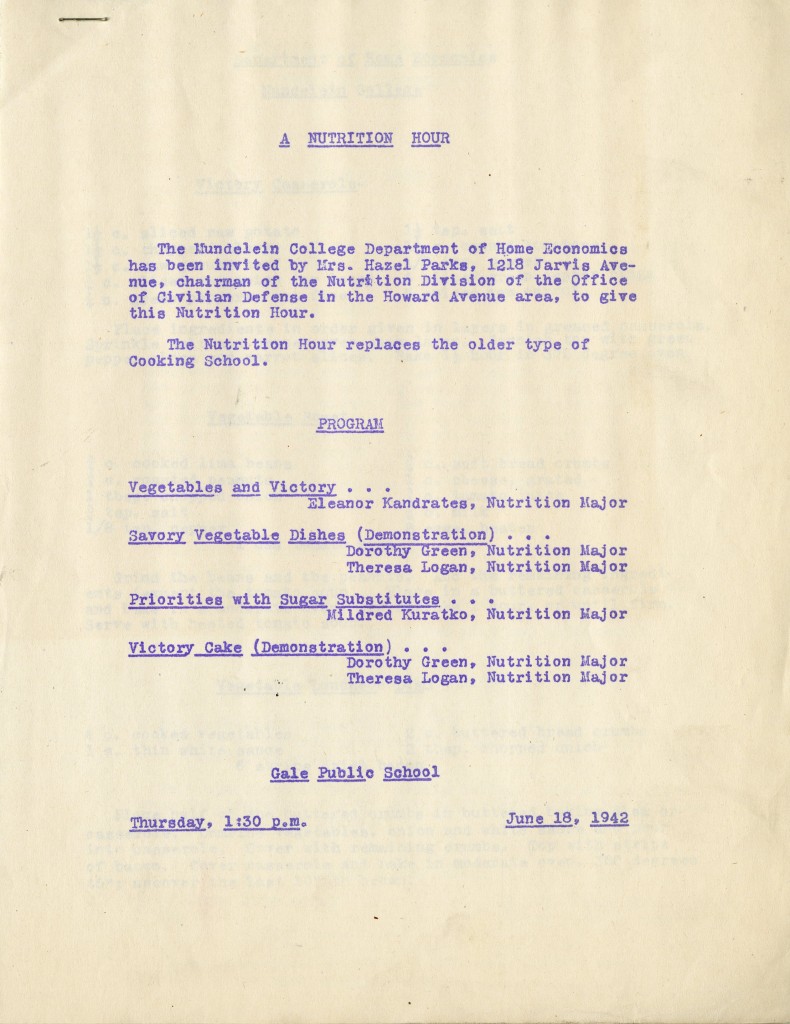

Home Economics students were also invited by the Nutrition Division of a local Office of Civilian Defense to present a Nutrition Hour program at which they gave cooking demonstrations and information on wartime nutrition to members of the community. Attendees were given recipes for dishes that used less of the rationed meat, sugar, and butter.

The Nutrition Hour event gave Mundelein Home Economics students the opportunity to share their research and knowledge about cooking nutritious, conservative meals.

Want to add some vintage flair to your upcoming holiday celebration? Try out some of these wartime Mundelein recipes! They are sure to lead you to victory!

Recipes from the Nutrition Hour program, June 18, 1942

Victory Casserole

1 1/2 cup cooked lima beans 1 1/2 tsp. salt

1 1/2 c. chopped celery 1 1/2 c. canned tomatoes

1 1/2 c. raw ground beef 1/8 tsp. pepper

1/2 c. sliced raw onion (or less) 6 slices green pepper rings1/4 c. green peppers, cut fine 6 slices raw carrot

Place ingredients in order given in layers in greased casserole. Sprinkle salt and pepper over each layer. Garnish top with green pepper rings and carrot slices. Bake 1 1/2 hours in 375 degree oven.

Victory Cake

2 1/4 c. sifted cake flour 2 tsp. grated orange rind

2 3/4 tsp. baking powder 1 1/2 tsp. vanilla extract

1/4 tsp. salt 1 c, white corn syrup

1/2 c. shortening 2 eggs, unbeaten1/2 c. milk

Sift the dry ingredients together three times. Cream shortening, orange rind and vanilla together until fluffy. Add syrup gradually , beating well after each addition. Add 1/4 of the flour mixture and beat until blended well. Add unbeaten eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition. Add remaining flour alternatively with the milk in halves, beating thoroughly after each addition. Turn into 2 greased and lightly floured 8″ cake pans. Bake in a moderately hot oven, 375 degrees for 30 minutes or until firm.

Victory Chocolate Icing

2 squares unsweetened chocolate

1 tbsp. water

1 and 1/3 c. canned sweetened condensed milk

1/4 tsp. almond extract

Melt chocolate in top of double broiler. Add milk and cook over boiling water for 5 minutes while stirring. Add water and almond extract. Cool and spread.

Caroline is a Graduate Assistant at the WLA and is working on her Master’s in Public History at Loyola University Chicago. Caroline is thankful for her husband and family, easy access to sugar, and cheesy holiday movies.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.