I took physics my junior year of high school. For me, physics was torture. Before taking the class, I thought that physics was mostly common sense, what goes up must come down and all of those old adages. Gravity was my seventeen year old nemesis; I stumbled around the hallways of my high school sometimes tripping over thin air. The only thing I can actually remember from that class is the fact that we made catapults and trebuchets and launched random objects out of them. We tried to hit unsuspecting victims in the head with ping pong balls and tangerines. It was a swirl of equations and variables that I could never keep straight. When I wonder what on earth possessed me to take that class, the only thing I remember with clarity are the words my mother told me when I asked her which of the sciences I should take to fulfill my last science credit, “Take physics,” she said, “not enough women take physics.”

What I did not know at the time was how right my mother was. The American Physics Society reports on their website that less that 20 percent of women earn bachelor’s degrees in physics. Furthermore, the amount of women who go on to do post doctorate work in the field, completing scholarly training or mentored research so that they can pursue a career path, is closer to 15 percent. The absence of women in physics, and the STEM disciplines in general, is a problem that the Obama administration has made a point to address; however, there is still a long way to go before there are an equal number of women and men earning higher education degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. The WLA is lucky to have a solid representation of women who have made contributions to the fields of science and mathematics, but there is one in my opinion that particularly stands out.

Born July 20th 1902, Sister Mary Therese Langerbeck spent her long life teaching and working in various disciplines within the sciences. Sister Langerbeck began her academic career at Northwestern, where she received her Bachelor’s degree in botany. She received her Master’s in 1945 in astronomy from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and would later go on to receive her Ph. D. in astronomy from Georgetown in 1948. It is mentioned by her colleagues that Sister Langerbeck was the first woman to receive a doctorate from Georgetown University. It is also noted that when she graduated she was the only sister in the entire world to hold a Ph.D. in astrophysics.

Sister Langerbeck spent much of her academic career as the chair of the Physics Department of Mundelein College. She orchestrated the building and implementation of two major scientific instruments on Mundelein’s campus. The first was a Foucault pendulum, a device used to measure the earth’s rotation, built in one of the Mundelein’s elevator shafts in 1938. The Foucault pendulum is a clear visual representation of the Earth moving beneath the pendulum, rather than the pendulum moving on its own. According to a Loyola World article published in 1993, the Mundelein pendulum was the longest of its kind in existence when it was built. The Mundelein pendulum’s accuracy was well known–scientists from all over the city of Chicago and the country used it’s readings for their research. Eventually, the Mundelein pendulum was retired in 1958 when a longer and more modern one was installed at the Chicago Museum of Science and Technology. Sister was also instrumental in building an observatory and telescope for the use of Mundelein’s students.

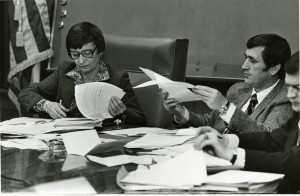

A student takes notes from the Mundelein pendulum that hung in an empty elevator shaft Mundelein College. 1938.

In the later years of her career, from 1971 until her retirement in 1977, Sister taught as a visiting professor of physics and mathematics at Livingstone College in North Carolina. She died at the age of ninety-one in 1993 of a heart problem, and was buried in the BVM Cemetery in Dubuque, Iowa. Sister Langerbeck is memorable not only for her own scientific accomplishments, but because she fought for the place of women in the sciences. In 1945, she published an article entitled, Some Reasons why Physics is Elected by So Few Freshman Students; Suggested Remedial Measures., one of Sister Langerbeck’s findings concluded that 52 percent of the women she questioned felt they would not be welcome in those fields if they expressed an interest in pursuing a career. Unfortunately, 70 years after her article was published, the same feelings of exclusion for women in the sciences persist. However, rather than feeling depressed by this statistic, I choose to feel hopeful that there are more teachers and mentors out there like Sister Langerbeck to inspire young girls to pursue their talents and skills in male-dominated fields, and kick butt doing it.

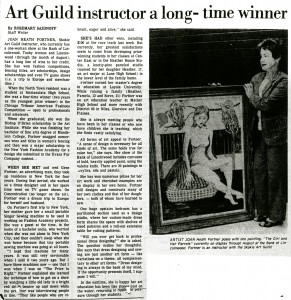

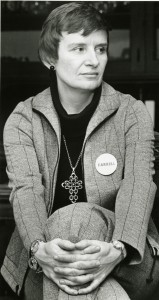

Feature on Sister Langerbeck, published in BVM Vista December 1959. The picture used for the article shows Sister in the physics laboratory on Mundelein’s campus.

Ellen is a Graduate Assistant at the WLA and is in the first year of her M.A in Public History at Loyola University Chicago. Before moving to Chicago, Ellen was a Kindergarten teacher in Louisiana. She enjoys brunch, procedural dramas, and pugs.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Differences of opinion are encouraged. We invite comments in response to posts and ask that you write in a civil and respectful manner. All comments will be screened for tone and content and must include the first and last name of the author and a valid email address. The appearance of comments on the blog does not imply the University’s endorsement or acceptance of views expressed.