A blast from the past describes my experience inventorying the Maria Pappas Papers at the Women and Leadership Archives. Although, a blast from a much more recent past than you may picture when you think of a historical archive. This inventory experience was like a journey back to my childhood. Inventorying the materials in an archival collection does not only mean combing through centuries old photos and letters. Sometimes it means cataloguing VHS tapes and CDs, which was my experience inventorying the audiovisual (AV) materials in the Maria Pappas Papers.

Inventorying AV was different from my experiences inventorying other collections, which were mainly made up of written documents, correspondence, books, and photos. When I look through this material I am able to learn a bit about the people and stories in the collection. Inventorying the AV portion of the Maria Pappas Collection was a different experience, as I could only learn as I inventoried through the titles of CDs, audiocassettes, VHS tapes, and more unique AV material I have never seen before, like U-matic videocassettes and 1” open reel audio. To learn more about the contents of the materials I would have to play them, and archivists often avoid playing AV to help preserve them. You never know when playing a VHS tape if that is the last time it will play. This was the primary reason I was inventorying the AV materials, so we could digitize many of these items, making them more accessible. Fortunately, I was able to find out more about Maria Pappas through delving into her print documents in our collection.

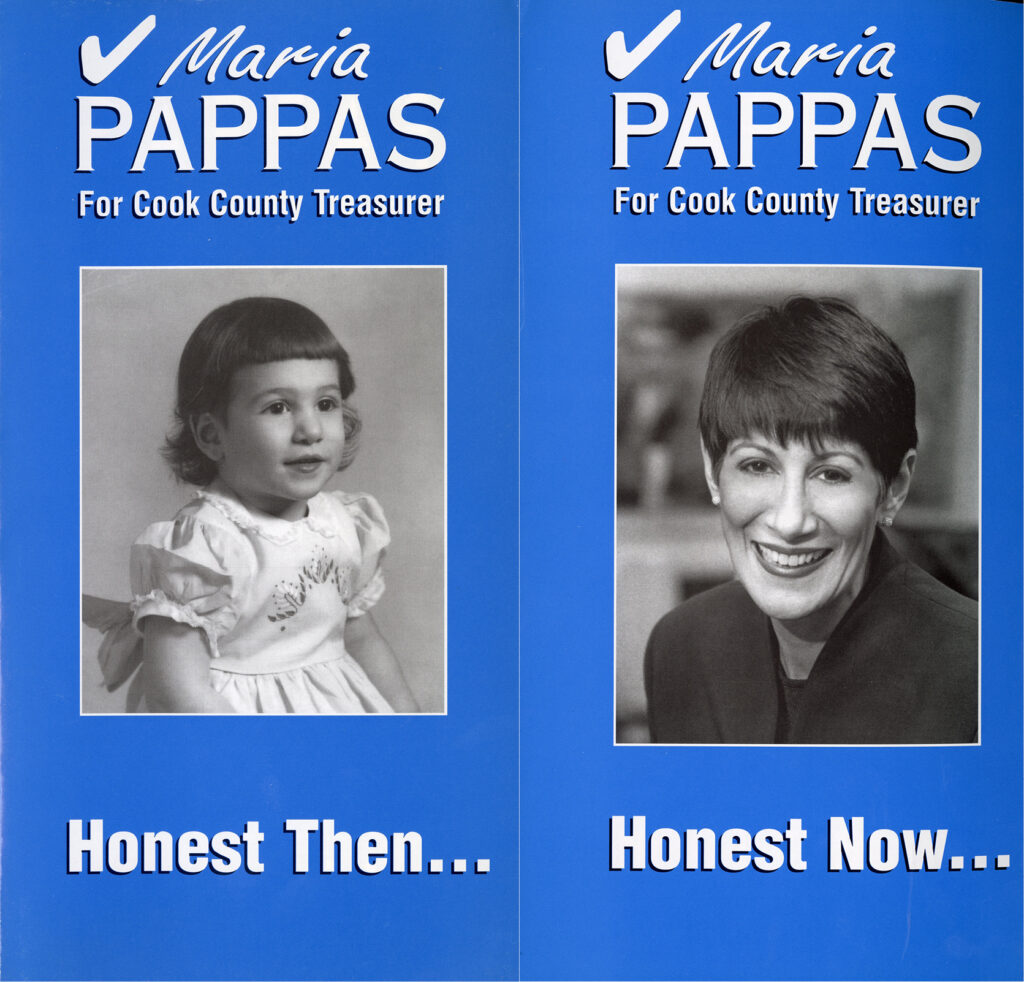

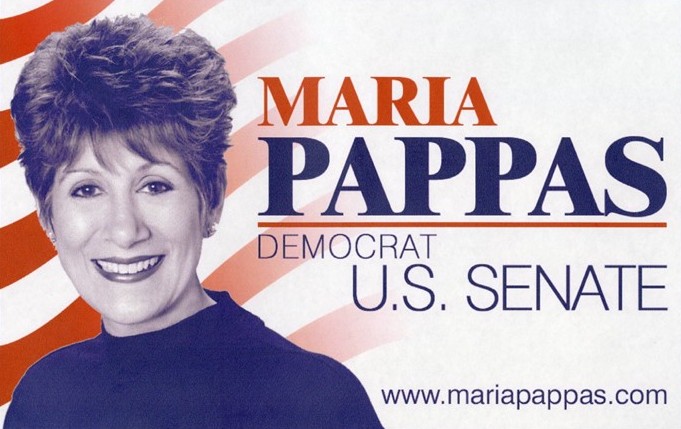

Maria Pappas was born in Warwood, West Virginia on June 7, 1949, to first generation Greek American parents. She is a lawyer and received many degrees, including a doctorate in Counseling and Psychology at Loyola University Chicago in 1976. She gained an interest in public service when she began working at the Altgeld Gardens public housing project in Chicago and ran a youth drug prevention program called the One Day One Drug Abuse Center. Testifying in court cases involving young people included visiting prisons and jails, an experience which led her to go to law school and consider public service. She ran for Cook County Commissioner in 1991 and was elected, then in 1998 ran for Cook County Treasurer and won. She made the Treasurer’s Office more efficient and technologically updated and was reelected five times in 2002, 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2019.

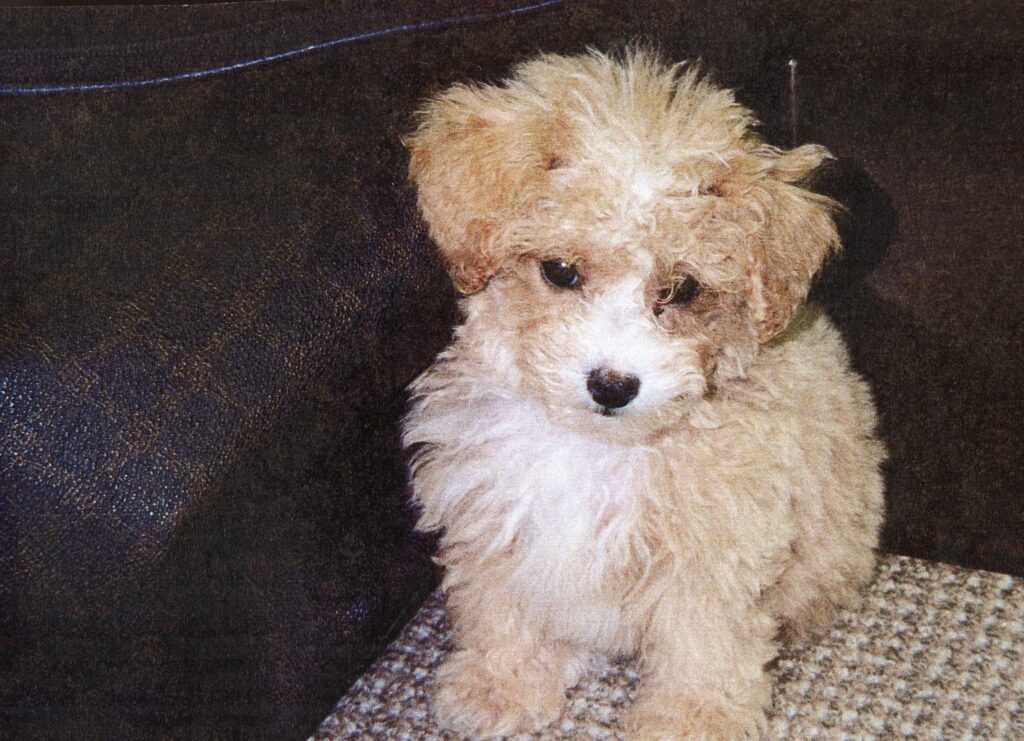

As a researcher I would love to learn more about Maria Pappas’ career through watching her audiovisual materials. One that particularly caught my eye when I was inventorying was a VHS tape titled “Treasurer Maria Pappas and her dog Koukla NBC”. Immediately I was intrigued. Why was Maria Pappas’ dog on NBC? I had to find more information about Koukla.

I was able to find some photos of Koukla in our collection which were super cute.

I was not able to find the video of Koukla and Maria Pappas on NBC online, so to find more information I turned to Google and found a Roll Call article discussing the 2008 Illinois Senate Race when Maria Pappas ran for Illinois State Senator and lost to Barack Obama.

The article states, “Pappas’ official biography notes that she plays the piano and is known for twirling a baton in area parades and competing in triathlons. She also carries a toy poodle, Koukla, in her purse” (Whittington). The article then goes on to quote David Axelrod, a media consultant to Barack Obama who said of Maria Pappas, “She twirls her baton and tours with her dog. But people like her. I don’t think people should underestimate her”. (Whittington). Relatedly, another VHS tape I inventoried was titled “Pappas Baton Twirling at Columbus Day Parade, Senate Candidate (1)”. This would be another great tape to view once it is digitized and see Pappas’ baton twirling in action. Finding more information about Koukla, and learning that Pappas would carry him in her purse, makes me excited to have this and other AV material digitized. Once these VHS tapes are digitized it will be much easier to send the video to researchers who request it. In the future these videos can be added to Preservica, and by searching the Women and Leadership Archives digital collection anyone can see Maria Pappas twirling her baton. We no longer need to lug out old technology, like the 1990s TV with a VHS player I watched The Lion King on as a kid, to see the adorable Koukla on video.

Sources

Whittington, Lauren. “Populist Pappas”. Roll Call, 9 September 2003.

https://rollcall.com/2003/09/09/populist-pappas/

“About Maria”. Maria Pappas, Committee to Elect Maria Pappas, 2022.

https://www.mariapappas.net/about

Max is a graduate assistant at the Women and Leadership Archives and a student in the History Master’s program at Loyola. For more information about this post, contact wlarchives@luc.edu.

Loyola University Chicago’s Women and Leadership Archives Blog is designed to provide a positive environment for the Loyola community to discuss important issues and ideas. Questions? Please contact the WLA at wlarchives@LUC.edu.